Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

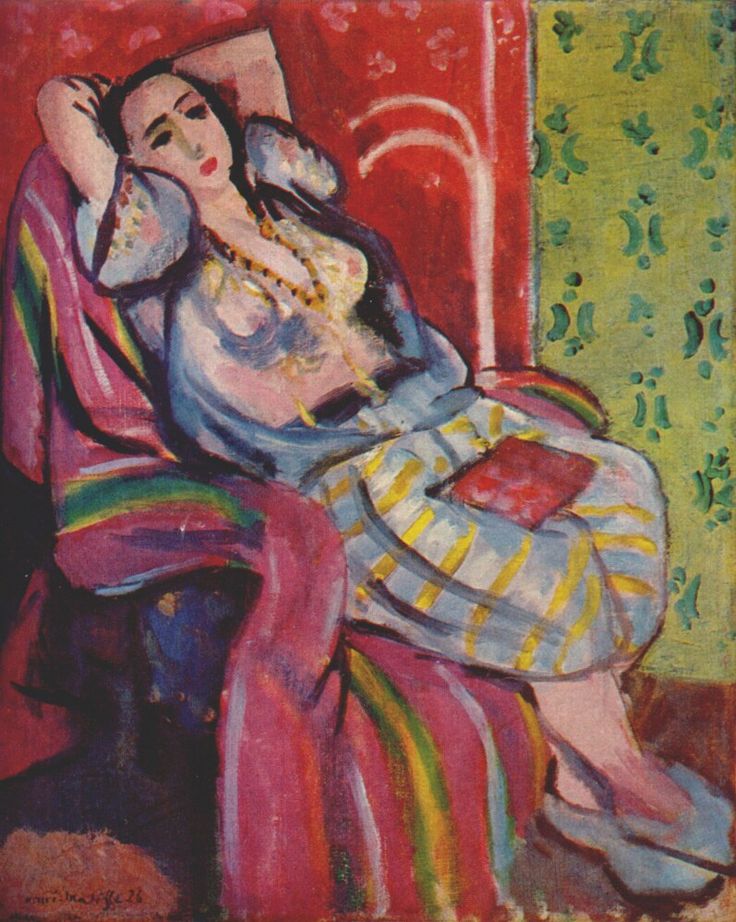

Henri Matisse’s “Odalisque” (1926) stages a relaxed, radiant conversation between body, textile, and wall—a compact interior where pattern does the heavy lifting and color becomes architecture. The model reclines in an armchair, arms lifted behind her head, the torso loosely wrapped in a transparent blouse and skirt whose lemon and dove-gray stripes play against a crimson ground and a panel of spring green. A violet shawl with rainbow bands falls over the chair in slow waves, and a red book rests lightly on the model’s lap like a punctuation mark. Nothing in the room is neutral. Every surface participates in the harmony, so that repose feels charged, the way a held musical chord throbs with energy even as it stays still.

The Nice Period As A Laboratory Of Calm

By the mid-1920s Matisse had settled into the disciplined routine of his Nice years, working in light-filled rooms whose shutters softened the Mediterranean sun. The Nice interiors replaced Fauvist shock with a lyrical classicism: not less color, but better tuned color; not less freedom, but freedom organized by intervals and contours. “Odalisque” belongs squarely to this project. The theme allows a languid pose and an abundance of textiles, but the artist refuses theatrical exoticism; he treats the subject as a studio instrument. The room is a laboratory where a modern idea of calm is engineered through relation—warm set against cool, curve answered by stripe, figure held by ground.

Composition As Reclining Arc

The whole painting leans on a reclining arc that begins in the model’s uplifted hands, flows through the brow and breast, dips along the waist, and rises again at the knees. The chair amplifies that movement with its enveloping crescent, while the long diagonal of the skirt points to the lower right corner, anchoring the pose. Matisse counters this sweep with a vertical seam created by the meeting of red wall and green panel on the right. That seam does the work of a spine: it holds the surface upright so the rest can undulate without losing balance. The red book secures the center of gravity; the rainbow shawl weights the lower left. Nothing is centered, and yet the picture never tips. The eye loops again and again through this reclined S-curve, discovering fresh alignments with each circuit.

Pattern As Structure, Not Ornament

The interior is a concert of patterns that behave like structural beams. The red wall is flecked with pale decorative motifs and traced with a white arch that echoes the model’s lifted arms. The green panel at right carries small paired shapes in a repeating cadence that reads like a quieter countermelody. The skirt’s stripes clarify the turning of the legs without heavy modeling. The shawl’s bands reprise the primaries—red, yellow, blue—while mixing in violet and emerald so the spectrum feels full but not noisy. Because each pattern has its own tempo, they interlock rather than fight. Pattern becomes the grammar of the room, a disciplined syntax that translates the odalisque’s languor into balanced measure.

Color As Emotional Architecture

Color carries the mood and organizes space. The wall’s carmine bathes the room in warmth, echoed by the book and by small crimson touches in the blouse. The green panel cools the chord and sets the figure forward. Violet shadows run through blouse and chair, joining the crimson’s heat to the green’s cool in a middle register. The flesh is a humane mixture of apricot, pearl, and faint lavender, catching reflected color from textiles without losing its distinct temperature. Lemon stripes on the skirt, beads around the neck, and glints on the shawl provide high notes that prevent the harmony from settling too low. Blacks and near-blacks are sparingly used to articulate the face, lashes, necklace, and the inner seams of the chair; whites are rarely pure, tending instead toward pearl or bluish milk so they belong to the room’s atmosphere rather than sitting on top of it.

The Figure’s Presence And Modern Agency

Although the title invokes a loaded genre, the model in this painting reads as a contemporary person at ease in a staged interior. The relaxed, almost athletic placement of the arms opens the chest and lengthens the torso; the tilted head and half-closed eyes suggest inwardness rather than display. The red book on the lap adds a note of private life—a reminder that this odalisque thinks as well as lounges. Matisse refuses the voyeuristic script historically assigned to the motif. He shows a figure who anchors the room through the dignity of her silhouette, not through melodrama or costume.

Drawing And The Soft Authority Of Contour

Matisse builds the figure with a few unflinching lines that thicken and thin as forms turn. The cheek is a single arc, the nose a plane, the mouth a small dark pressure that holds the face in balance. The blouse is cut by edges that tighten at seams and relax into airy transparency across the torso. The skirt’s hem meets the calf in curves that feel breathed, not measured. Even the chair’s bulges are mapped by lines that acknowledge movement rather than imprison it. This drawing does not chase anatomy; it seeks the right boundary for color to do its work. It gives the painting its quiet authority.

Light, Shadow, And Mediterranean Diffusion

The light is Riviera soft—diffuse, bounced from wall and cloth rather than blasting from a window. Shadows are transparent and chromatic, violet in the folds of the blouse, olive at the edge of the chair, a cool gray along the shin. This approach lets color carry modeling. Where the blouse overlays the breast, for instance, a transparent bluish pass turns flesh without denying its warmth underneath. Along the neck and face, small patches of cooler paint let the skin sit in space without severing it from the rosy wall. Instead of chiaroscuro theatrics, the painting breathes with temperature shifts.

Textiles And The Tactile Intelligence Of Paint

Matisse differentiates materials through touch as much as through color. The shawl’s rainbow bands are laid with long, loaded strokes that leave ridges, implying nap and weight. The blouse is built from thin veils that allow underpainting to whisper through, mimicking gauze. The skirt’s stripes alternate between denser yellow notes and softer gray passages, the difference itself becoming a kind of texture. The wall is brushed more broadly, a slightly granular surface that feels like painted plaster; the green panel’s smaller dabs suggest printed fabric. This tactile variety keeps the setting legible as a world of distinct substances while insisting on the primacy of paint.

Space, Depth, And Productive Flatness

The space is shallow by design. The chair presses forward, the model sits very near the surface, and the wall panel behind acts like a flat decorative screen. Yet depth is not abolished. Overlaps—the arm over the head, the book on the lap, the skirt over the leg—create believable stacking, and the chair’s inner shadows open just enough volume to seat the figure. This oscillation between object in space and pattern on surface is a hallmark of Matisse’s Nice period. It keeps attention on the surface where relations happen while maintaining a minimum of depth to sustain human presence.

Rhythm, Music, And The Time Of Looking

Matisse’s favored analogy to music is audible here. The wall’s tiny motifs are a soft percussion; the shawl’s bands and the skirt’s stripes run as elongated measures; the figure’s S-curve sings a legato melody across the field; and the red book strikes a clear, immediate note. The painting invites adagio looking. One traces the arc from hands to feet, pauses at the book, crosses to the green panel, drifts back along the shawl, and returns to the face. Each circuit reveals fresh counterpoints: a yellow bead rhyming with a skirt stripe, a violet shadow answering the chair’s blue, a white arch on the wall completing the lifted-arm shape.

Orientalism Reconsidered

Matisse knew the weight of the odalisque tradition and the dangers of exoticism. In this canvas he redirects the motif toward pictorial inquiry. The “otherness” once projected onto the subject is relocated to color and pattern—domains that operate democratically across figure and furniture. The model’s modern haircut and the studio props confirm that we are in a contemporary room, not an imagined harem. What remains from the historical genre is permission: permission to stretch the body into languor, to flood the field with textile, and to let the decorative lead. The painting’s ethical stance lies in its equality of parts.

Dialogues Within Matisse’s Oeuvre

“Odalisque” speaks to the broader body of Nice interiors. Compared with the pearly restraint of “The Pink Tablecloth,” this canvas is hotter and more saturated. In relation to “Odalisque with Green Scarf,” it trades the striped backdrop and turquoise furniture for a simpler two-panel wall, then intensifies the chroma of the chair and skirt. With the later cut-outs in mind, one notices how silhouette already behaves like cut paper—the figure nearly reads as a single shape set against red and green planes. Across these dialogues, the painting shows the consistency of Matisse’s project: to reach clarity not by reducing sensation but by arranging it.

The Red Book As A Small Center

That little book on the lap is a masterstroke of economy. It punctuates the torso’s curve, stabilizes the middle of the composition, and repeats the wall’s crimson in a higher, concentrated key. Its rectangularity also counters the whole room’s dominance of curves and stripes, and its small area of dense pigment testifies to Matisse’s sense that a quiet painting needs a few concise, saturated moments to keep the chord alive. Whether the model is reading or resting is left undecided; the book’s role is formal first, intimate second.

Material Presence And Evidence Of Process

Pentimenti remain visible upon close looking: a contour moved at the thigh and softened; a band in the shawl adjusted to better align with the chair; a pale arch on the wall repainted to echo the arms more directly. These traces do not disturb the calm; they thicken it with time. They allow viewers to feel the search inside the serenity, the way a musician’s subtle vibrato gives a sustained note its human depth.

Why The Painting Endures

The canvas endures because its pleasures are structural and renewable. Each return yields a new hinge: a lemon stripe aligning with a necklace bead; a violet shadow answering a blue band; a tiny black accent in the bracelet echoing the calligraphy of the eye. The composition’s loop always brings you back to the face, which—despite the room’s saturation—remains the work’s quiet center. This durability arises from the accuracy of relation. When edges, hues, and intervals are right, they welcome repeated attention without fatigue.

Conclusion

“Odalisque” is a compact manifesto of Matisse’s Nice-period art. A reclining figure, a pair of animated walls, a cascade of textiles, and a single red book become the means by which he proves that the decorative can be profound. Color is not an afterthought; it is the architecture of feeling. Pattern is not embellishment; it is the grammar that makes calm readable. Line is not outline; it is breath. The canvas invites viewers to settle into its tempo, to recognize in its poised relations a humane vision of pleasure—pleasure disciplined into harmony, warmth held by cool, languor steadied by measure. In that balance, the painting finds a modern, durable grace.