Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

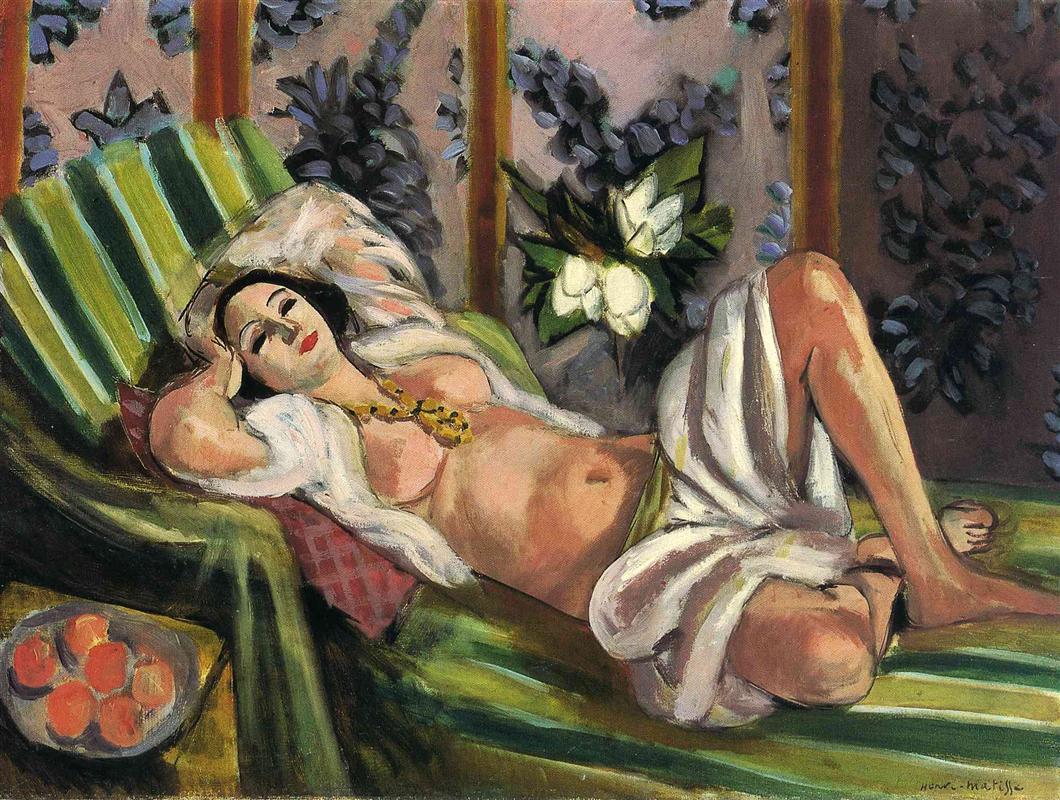

Henri Matisse’s “Odalisque” (1926) is a luxuriant statement from his Nice years, a period when he turned intimate interiors into laboratories for color, rhythm, and poise. A reclining model rests on a striped divan, draped loosely in a white cloth, her torso exposed and her legs folded in a relaxed knot. Behind her, panels alive with leafy silhouettes and a large white blossom turn the wall into a breathing tapestry. The mood is languor without stupor, pleasure organized by measure. With a small bowl of oranges at the lower left and the steady beat of green stripes across the bed, Matisse composes a quiet orchestra in which body, fabric, foliage, and fruit each hold a voice.

The Nice Period and the Decorative Intelligence

By the mid-1920s, Matisse had refined the audacity of Fauvism into a calm modern classicism. Nice offered steady Mediterranean light, manageable rooms, and a daily routine of arranging models among textiles, plants, and simple props. The odalisque—historically a European fantasy—became a flexible studio motif that permitted relaxed poses and patterned surfaces without the burden of narrative. In this canvas he directs the theme away from exotic spectacle and toward formal exploration. The figure is not a character; she is the axis around which color and pattern negotiate harmony.

Composition as a Reclining Chord

The composition hinges on a long diagonal. The model’s head lies high at left, cushioned by a green-striped bolster, while her knees rise at the right edge, turning the body into a supple S-curve that spans the width of the canvas. This diagonal is countered by the near-horizontal edge of the bed and by the verticals of the wall panels. Matisse uses the striped coverlet to reiterate the diagonal like a melody carried on a ground bass. The bowl of oranges near the lower left anchors the scene and begins a slow loop: fruits to reclining torso to white blossom to bent knees and back again. Nothing is centered. The eye moves in a measured circuit, discovering each element as part of a broader phrase.

Pose, Presence, and Modern Agency

The odalisque rests but does not dissolve into the furniture. One arm flips lazily behind the head; the other slides toward the waist; the head tilts slightly forward; the mouth is closed but not tense. Her gaze feels inward rather than performative. The pose is theatrical only in the sense that it exhibits the figure’s curves as compositional arcs. Modernity lies in this balance of intimacy and agency: the model is not a passive sign of “the exotic” but a calm collaborator in the painting’s order.

Color as Architecture and Atmosphere

Color supplies structure and mood. The bed’s greens move from cool jade to olive and sap, traversed by crisp bands of pale yellow that catch light. The figure’s flesh is a chord of peach, rose, and warm gray; cooler notes collect in the shaded abdomen and along the arm where the wall’s violet-gray seeps into skin. A large white flower opens behind the torso, its cool center and dark leaves setting off the warmth of the body, while the wall panels hum with subdued mauves and twilight blues. Bright orange fruit punctuates the lower left, repeating the body’s warm register at a concentrated pitch. The palette is high-keyed but tuned: each color has a partner that keeps it from shouting.

Patterned Wall and the Theater of the Studio

Matisse often builds his interiors with textiles and screens that press forward like tapestries. Here the wall behaves as a decorative field patterned with leafy silhouettes, a few of which darken toward near-black. The large blossom functions as a visual pause between the model’s torso and knees. This wall keeps the space shallow—more like a stage set than a receding room—so the viewer remains with the relationships on the surface. The decorative is not an overlay; it is the framework that steadies the figure.

The Authority of Contour

Line does quiet, decisive work. The jaw is a single curve; the shoulder turns with a soft thickening of paint; the knee is a crisp arc reacting against the drape. The white cloth is not modeled with hatching but with edged planes, one cool, one warm, that turn over the thigh and meet at ridges where paint is slightly raised. Matisse avoids brittle outlines; even when the contour darkens, it never becomes graphic. Line here is breathing boundary—tight where bone is close to skin, relaxed where flesh meets light.

Light, Shadow, and Mediterranean Diffusion

Light arrives from the upper left and diffuses across the figure and bed. This is not spotlight but air; shadows are violet-gray and olive rather than black. The face receives a pale veil that softens features without erasing their geometry. Along the torso, light moves in long phrases—bright at the shoulder, moderated at the ribs, warmed at the abdomen, cooled along the flank—so form emerges from temperature shifts rather than theatrical contrasts. The result is an atmosphere of steady warmth that feels true to Nice, where sunlight is filtered by shutters and reflected by pale walls.

Textiles and the Discipline of Stripes

The green-striped coverlet is more than decoration; it’s a regulating device. Stripes carry the bed’s tilt, echo the diagonal of the pose, and keep the plane readable. Their measured spacing supplies a rhythm against which the soft flesh can register. The bolster’s broader stripes at the head deliver a second meter in higher key, drawing the eye toward the face without isolating it. These textiles demonstrate Matisse’s belief that pattern, handled with restraint, is structural—an armature for harmony.

Space, Depth, and Productive Flatness

Space is shallow by design. The bed tilts forward, the wall presses close, and the figure occupies a zone only slightly deeper than the width of her own body. This productive flatness keeps attention on surface relations, where Matisse’s principal drama takes place. At the same time, small cues—a receding edge of the mattress, the turning of the knee, the bowl’s oval shadow—maintain enough depth for the scene to breathe. You oscillate between reading a body in a room and savoring a tapestry of shapes.

Rhythm, Music, and the Time of Looking

Matisse often likened painting to music. The analogy fits. The bed’s stripes beat a measured time; the torso’s curve sings a legato line; the white blossom is a bright chord; the oranges are small, percussive strikes. Viewing becomes listening with the eyes. The painting invites an adagio tempo—slow, looping circuits that yield fresh correspondences: the necklace’s yellow echoing a bed stripe, the blossom’s white rhyming with folds in the drapery, a cool violet shadow aligning with a wall panel’s tone.

The Bowl of Oranges and the Scent of Place

At the lower left, a shallow bowl holds oranges painted with quick, rounded strokes. They inject the room with a sensory memory of the Riviera—the smell of citrus, the weight of ripe fruit. But their role is formal as much as fragrant. They stabilize the composition’s left edge, balance the weight of the bent knees on the right, and restate flesh tones in a more saturated, compact key. Their circular forms also counter the long stripes and the elongated body, completing the painting’s geometry.

Orientalism Reconsidered and Redirected

The word “odalisque” carries a history of Orientalist fantasy. Matisse acknowledges the theme—drapery, lounging pose, jewelry—yet redirects it. The model’s modern haircut and composed expression, the European studio furniture, and the frankness of paint unhook the image from voyeuristic romance. Here, “odalisque” is a studio motif that permits relaxation and pattern play. The painting’s real subject is the ethics of relation: how figure and ground can coexist without hierarchy, how pleasure can be structured without becoming trivial.

Material Presence and Evidence of Process

The surface retains the tactility of its making. In the wall, pigment is scumbled thinly so the ground breathes through; in the bed stripes, strokes are longer and creamier; in the flesh, layers alternate between lean and loaded, leaving soft ridges where the brush turned. Small corrections remain visible: a contour moved and softened along the thigh, a leaf darkened to better hold the torso’s edge, a highlight re-laid on the shoulder. These traces are not noise; they record the decisions that produced the painting’s composure.

Dialogues Within Matisse’s Oeuvre

This canvas converses with other Nice interiors—a sister to “Grey and Yellow Odalisque” in its intimate pose, a cousin to the patterned rooms with pianos and bouquets. Compared with the frontal seated odalisques, this reclining version is more melodic, aligning the figure with fabric currents. It also anticipates the late paper cut-outs in the way silhouette becomes paramount: the body reads nearly as a single interlocking shape against a flattened field of pattern and color.

Psychological Tone and Viewer Experience

The psychological register is one of collected ease. The model’s face—eyes lowered, lips softly marked—suggests inwardness rather than display. The viewer’s experience mirrors that mood. As your gaze traces the bed’s diagonal, rests at the white blossom, and returns through the oranges to the face, the painting regulates your breathing. It is not hypnotic; it is steadying. The calm is not emptiness but a crafted balance that lets sensations accumulate without clamor.

Why the Painting Endures

“Odalisque” endures because its pleasures are structural and renewable. Each return discloses a new hinge: a bed stripe aligning with the necklace, a blossom’s white echoing a drapery fold, a violet shadow answering a leaf, a small red note in the lip finding a partner in an orange. The painting’s generosity lies in those repeating discoveries. You come back not for a story but for consonance—the sense that the room, the model, and the viewer are hosted by the same measured, luminous order.

Conclusion

In this 1926 “Odalisque,” Matisse compresses his Nice-period convictions into a radiant interior: color as architecture, pattern as structure, contour as breath, and calm as a worked achievement. The figure reclines like a melody carried by the steady rhythm of stripes; flowers and fruit add counter-phrases; the wall keeps the surface forward so harmony can be heard. Without narrative fanfare, the painting demonstrates how the decorative can be profound—how a room arranged with care can become a chamber of well-being, and how a human presence can organize that chamber without dominating it. The result is a durable chord, warm and lucid, that continues to sound.