Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

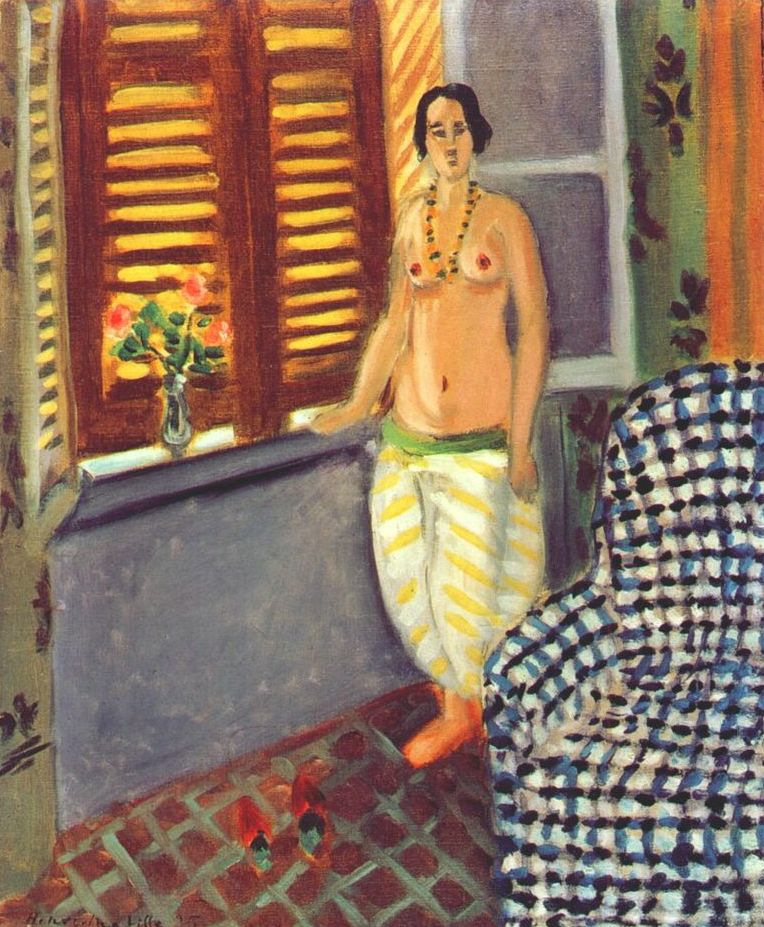

Henri Matisse’s “Odalisque” (1925) is a quintessential work of his Nice years, when he transformed intimate rooms into stages for color, pattern, and poise. A standing model, bare-chested and adorned with a bead necklace, rests by a shuttered window. She wears loose white trousers banded with lemon-yellow stripes, while red slippers sit on a tiled floor nearby. The room is alive with decorative incident: a bouquet catches light on the sill, green patterned drapery hangs at the right, and a checked armchair pushes into the foreground like a soft chessboard. With a handful of everyday props and a deliberately simplified drawing, Matisse composes an image that feels at once serene and theatrical. The odalisque here is less a character from a distant tale than a catalyst for pictorial harmony.

The Nice Period And The Recasting Of The Odalisque

By the mid-1920s, Matisse had found in the French Riviera the conditions for the equilibrium he sought—luminous daylight, controllable interiors, and a steady practice of arranging models amid textiles, plants, and furniture. The odalisque theme, long burdened by European fantasies about the “Orient,” became for him a flexible studio motif. It permitted relaxed dress, languid attitudes, and an excuse for patterned fabrics, yet he stripped it of narrative exoticism. In this 1925 canvas the subject’s modern haircut, the ordinary window shutters, and the familiar armchair make clear that we are in the painter’s own rooms. The painting is not a transported harem scene but a meditation on how color, line, and light can turn a simple morning into a complete visual chord.

Composition As A Theater Of Relations

Matisse organizes the rectangle like a modest stage. A large shuttered window fills the left half of the composition, its warm ochres crossed by glowing slats. The model stands at the ledge, her weight dropped into one hip, arm relaxed along the sill, gaze slipping outward. She forms a vertical counter to the window’s strong horizontal bars. At the right, the gridded armchair with blue-black checks leans in diagonally, answering the window while framing the figure. The tiled floor—greens set into red-brown—tilts gently upward, a familiar Nice-period device that compresses depth and keeps the surface active. Across the image, diagonals and verticals interlock so the eye moves in a slow loop from shutter to face to trousers to slippers to chair and back again.

Color As Temperature And Architecture

Color is the true architecture of the scene. The shutters are a deep honeyed orange, pulsing with streaks of yellow where light threads between slats. That warmth reverberates in the flowers on the sill and in the small red shoes on the floor. Cooler notes stabilize the room: the wall around the window carries a lavender-gray wash, the ledge and base are soft slate, and the chair’s checks read as icy blue against black. The trousers, white shot through with lemon bands, mediate between hot and cool; their clean brightness lifts the lower half of the figure and pulls the gaze downward in a gentle cascade. No color sits alone. Each note is positioned to answer another, and the result is a chamber-sized harmony that glows without shouting.

Pattern As Structure Rather Than Ornament

Matisse’s interiors are famous for their patterned surfaces, and here pattern functions as structure. The shutter’s repeat bars pace the left side like a metronome. The tiled floor contributes a second grid, skewed just enough to keep the surface lively. The checked chair brings a third matrix into play, coarser and more tactile, its squares animated by thick strokes of blue and black. At the far right a hanging fabric, green sprigged with dark motifs, introduces sinuous shapes that soften all the geometry. These systems do not merely decorate; they organize space and regulate tempo, ensuring the figure remains legible while the room vibrates with subtle energy.

Light, Shadow, And The Mediterranean Window

The light in “Odalisque” is interior light filtered through shutters. It is warm and particulate, more glow than beam. The slats exclude harsh contrast and replace it with graded warmth that kisses the flowers, warms the wood, and strikes small accents along the edge of the ledge. On the model’s body, light appears less as shadow modeling than as temperature shift—warmer at the sternum and shoulders, cooler along the ribcage where the gray of the wall seeps in. The trousers catch the most direct reflection; their lemon bands seem to hold sunlight the way porcelain holds a memory of heat. This gentle lighting is central to the mood of the Nice period, where clarity is prized over drama.

The Authority Of Contour And The Economy Of Drawing

Matisse’s drawing is both soft and unyielding. The figure is enclosed by a calm, breathing contour that tightens at the jaw and loosens at the waist. Features are reduced to decisive planes—arched eyebrows, almond eyes, a firm red mouth—stitched into coherence by the contour rather than by heavy modeling. The necklace is a string of quick, luminous touches that guide the eye from face to torso without fuss. The chair’s checks are not meticulously ruled squares; they are blocks placed with a painter’s sense of rhythm. Everywhere, line functions like phrasing in music, shaping the passage of vision through the image.

Space, Depth, And Productive Ambiguity

The room makes sense as space but resists measurement. The floor recedes, yet its grid is elastic; the ledge is solid, yet it tilts; the chair advances into the viewer’s space like a friendly intruder. This ambiguity is a strategy, not a defect. It keeps attention focused on relations of color and pattern at the surface while allowing objects to remain believable. The window, especially, is a surface that pretends to be an opening: the slats behave like painted stripes as much as architectural elements. The painting thus oscillates between interior illusion and decorative flatness, a characteristic tension of Matisse’s mature work.

The Figure’s Poise And Modern Agency

Unlike many historical odalisques, the model here stands upright. Her shoulders settle but do not slump; her hips carry weight without display. She is not sprawled for a voyeur; she occupies a room with quiet authority. The beaded necklace reads less as exotic fetish than as a simple accent that echoes the warm shutter tones. Her trousers—voluminous but crisply striped—deliver a key chromatic and rhythmic role while granting the figure a modern modesty. In this way Matisse recasts the odalisque not as fantasy captive but as axis of harmony, a collaborator in the room’s ordered pleasure.

The Bouquet, The Slippers, And The Intimate Stage

Two small details act like stage props that reinforce the scene’s intimacy. The flowers on the sill, painted with brisk, rounded touches, repeat the warm reds and yellows of the shutters in higher key and provide a soft counterpart to the figure’s torso. The pair of red slippers on the floor suggests the moment just before dressing or just after undressing—small narrative hints that deepen the mood without turning the painting into anecdote. Their placement also anchors the floor’s grid and keeps the lower left quadrant active, preventing the composition from top-heaviness.

Brushwork, Material Presence, And Evidence Of Process

Though the room reads as calm, the surface is alive with the touch of paint. The shutters are laid with confident, dragged strokes that leave ridges at the edges of the slats. The gray ledge is a veil of thin paint through which warmer undertones flicker, suggesting stone without describing it. The armchair’s checks are built from small, juicy dabs that sit on the surface like tesserae, giving the chair a woven presence. Flesh passages are thinner, allowing the ground to breathe through. These varied applications keep the painting sensuous in the literal sense—the viewer feels how it was made—and bind content to method, as the subject’s poised ease is matched by the painter’s poised touch.

The Window As Threshold And Picture-Within-The-Picture

The shuttered window is both subject and metaphor. It is a threshold between interior and exterior, but because the slats are closed, nature enters only as filtered warmth. The window’s rectangles echo the canvas’s own edges, making it a picture within the picture. In this way Matisse quietly reflects on the act of painting itself: the world arrives at the studio through a controlled aperture, and the artist modulates it into a balanced composition. The odalisque, stationed by this device, becomes the mediator between outside light and inside order.

Dialogues With Companion Works

This canvas converses with other Nice interiors from the same period—reclining odalisques on striped couches, women at pianos, dancers before red wallpaper. A common vocabulary unites them: patterned grounds that press forward, furniture treated as rhythm rather than burden, and figures whose calm centers the decorative field. Compared with the reclining odalisques, the standing pose here introduces a vertical dignity that recalls earlier portraiture while keeping the modern simplification of contour. The checked chair anticipates the cut-out era’s love of flat interlocking shapes, and the shutter bars rehearse the later habit of organizing surfaces into musical stripes.

Orientalism Reconsidered And Redirected

To call the figure an “odalisque” acknowledges a long tradition of European projections onto non-European subjects. Matisse’s contribution is neither a naive repetition of that fantasy nor a didactic repudiation; instead, he retools the motif for formal exploration. The trousers carry traces of the exotic, but they function most consequentially as a chromatic engine and as a rhythmic figure. The model’s upright stance and steady gaze resist the passivity historically assigned to the theme. Far from disappearing into ornament, she organizes it. The painting thus opens a space where beauty derived from difference is converted into a modern ethics of relation: pattern, color, and person held in respectful balance.

Psychological Tone And The Viewer’s Experience

The picture’s psychology is one of alert calm. The figure’s expression is neither coy nor severe; the head tilts slightly, the mouth is closed, the eyelids relaxed. The room is quiet enough that the viewer can hear its intervals—the measured bars of the shutters, the grid beneath the slippers, the breathing squares of the chair. Looking becomes a kind of listening. The eye glides at the tempo of an adagio, discovering correspondences that knit the space together, such as the necklace’s rhythm echoing the shutters, or the green motifs repeating from drapery to floor tile. The longer one looks, the more the painting’s serenity feels earned rather than merely given.

Modern Classicism And The Promise Of Harmony

“Odalisque” reads as a compact statement of modern classicism. The drawing is clear, the relations legible, the palette tuned; yet nothing feels academic. Matisse arrives at classic poise not by citing antiquity but by trusting the essentials—shape, color, interval, and touch. The result is a highly contemporary vision of order, one that neither suppresses sensation nor indulges restlessness. This promise of harmony, made in the volatile decades between wars, explains the persistent appeal of the Nice interiors: they demonstrate that calm can be an achievement, not an escape.

Why The Painting Endures

The canvas endures because its pleasures are structural. The viewer does not rely on story or virtuoso detail; instead, satisfaction arises from how parts hold together. Warm shutters meet cool walls, stripes converse with checks, a standing figure steadies a room eager to flicker into abstraction. Each return to the painting reveals another quiet hinge—a small red slipper catching the floor’s green, a necklace bead aligning with a shutter bar, a brushloaded square on the chair turning just enough toward light. In this disciplined accord, the odalisque ceases to be a borrowed figure and becomes the emblem of Matisse’s lifelong pursuit: a balanced, breathing art that dignifies everyday seeing.