Image source: artvee.com

Historical and Artistic Context

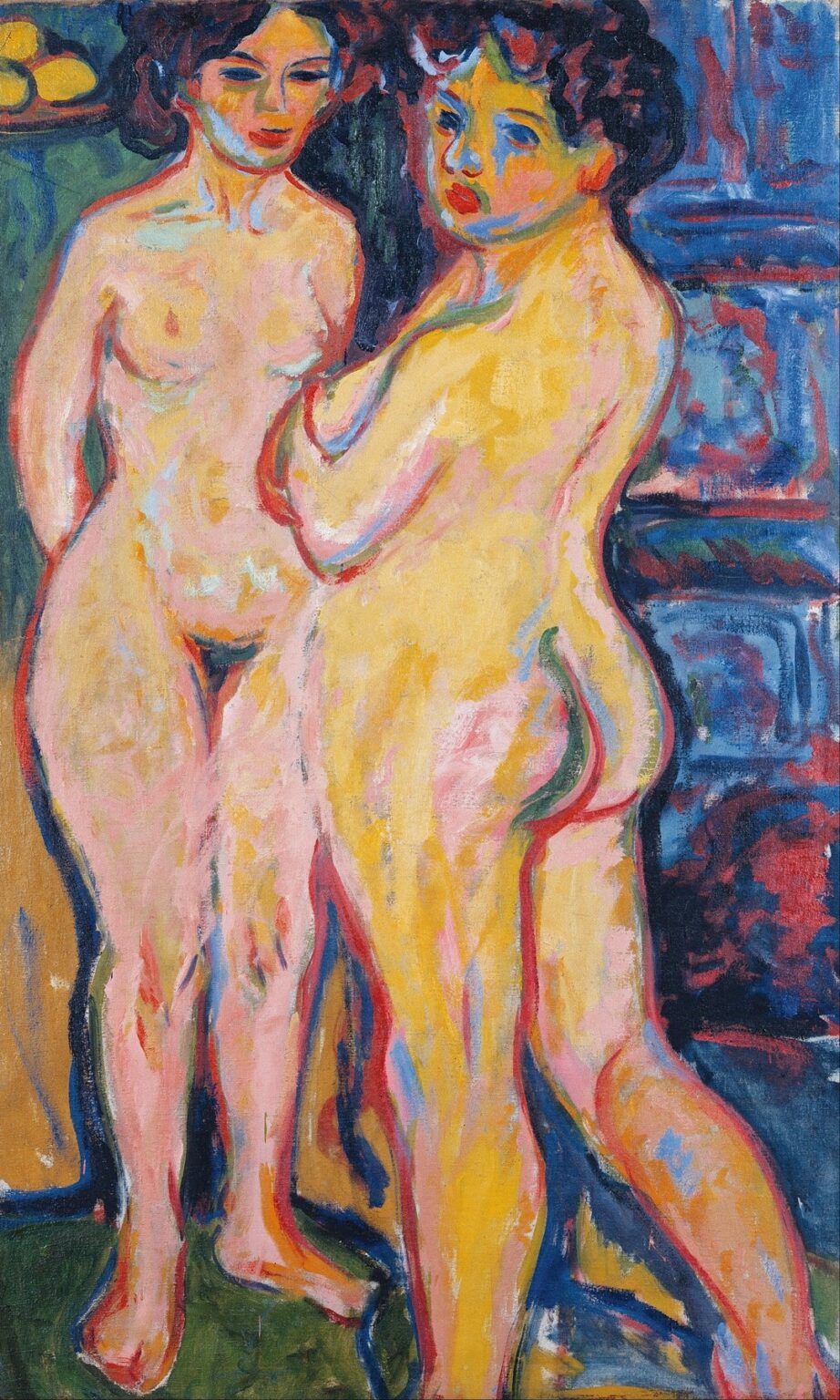

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s Nudes Standing by Stove (1907–08) occupies a pivotal position in early German Expressionism. Created during the formative years of Die Brücke (The Bridge), the painting reflects Kirchner’s rejection of academic naturalism in favor of raw emotional expression. Die Brücke, founded in Dresden in 1905 by Kirchner, Fritz Bleyl, Erich Heckel, and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, aimed to forge a new direction for painting—one that bridged past traditions and a more instinctual, primal future. By 1907, the group had relocated to Berlin, where the metropolis’s energy and social contrasts fueled their creativity. Nudes Standing by Stove synthesizes themes central to Die Brücke: the honest portrayal of the human form, the use of non-naturalistic color, and the flattening of pictorial space to emphasize psychological resonance over mimetic accuracy.

Kirchner’s Evolution to 1907–08

Kirchner began his career as an architecture student before embracing painting full-time under the tutelage of Lovis Corinth at the Dresden Academy. His early works displayed Corinth’s influence in draftsmanship and palette, but by 1905 Kirchner had turned toward a more primitive aesthetic—studying African sculpture and Japanese prints and refining a style marked by bold outlines and a sense of immediacy. By 1907, Kirchner’s brushwork had grown freer, his color scheme more experimental, and his subject matter shifted to the nude figure in intimate settings. Nudes Standing by Stove captures this transitional moment: the precision of academic training still underlies his draftsmanship, while Expressionist impulses propel his color and form into new territory.

Subject Matter and Social Significance

The nude has long been a staple of Western art, traditionally idealized and situated within mythic or allegorical contexts. Kirchner subverts these conventions by presenting his models as working-class women in a modest interior, gathered informally around a wood-burning stove. The domestic setting—or simple “atelier” interior—underscores social realities over classical reverie. These are not goddesses but real women whose unselfconscious presence invites both frank observation and empathy. In Berlin, Die Brücke artists often painted nude models drawn from their circle of friends and acquaintances, emphasizing authenticity and camaraderie. Here, the stove itself becomes a symbol of warmth and communal intimacy, reinforcing the painting’s themes of human connection amid urban alienation.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics

Kirchner arranges the three figures in a shallow pictorial space. The central woman faces the viewer directly, her hands clasped behind her back. To her left, a second woman stands in profile, her weight on one leg as she turns toward the stove. On the right, a third figure mirrors the central model but with a slight twist of her torso. The stove, painted in flat planes of green and ochre, anchors the background and creates a vertical axis that divides the composition. Behind and above the figures, a heavily patterned wall or curtained alcove, rendered in deep navy and crimson strokes, flattens spatial depth. The floor, suggested by broad strokes of olive and umber, tilts slightly upward—a deliberate distortion that emphasizes pictorial flatness and underscores the painting’s non-illusionistic thrust.

Color Palette: Expressionist Chromatics

Kirchner’s color scheme in Nudes Standing by Stove is deliberately non-naturalistic. The flesh tones range from lemon yellow to rose pink, punctuated by strokes of cadmium blue and green that outline musculature and shadow. These arbitrary hues convey emotional intensity rather than anatomical accuracy. The stove’s deep green stands in contrast to the figures’ warm tones, while the background’s dark reds and blues create a brooding atmosphere. Highlights of raw cadmium yellow on the stove’s top and the figures’ shoulders draw the eye, creating visual rhythm. This discordant yet harmonious palette underscores the protagonists’ psychological presence, making color itself a vehicle for emotional communication.

Brushwork and Surface Texture

Kirchner’s handling of paint combines broad, energetic sweeps with incisive linear accents. The background’s dark drapery emerges from layered, diagonal brushstrokes, leaving visible striations that vibrate like nervous energy. On the stove, thicker impasto emphasizes its solidity, while the figures’ bodies bear looser, more flowing strokes that echo the rhythms of heated air around the fire. The interplay of smooth areas—such as the central figure’s torso—and textured passages—like the stove’s ornate detailing—imbues the canvas with a palpable tactility. Kirchner’s brush remains visible throughout, a testament to Expressionism’s prioritization of the artist’s gesture as an index of feeling.

The Stove as Symbol and Visual Anchor

The wood-burning stove serves both narrative and formal purposes. Functionally, it provides heat in the chilly atelier, offering a plausible reason for the figures’ gathering. Symbolically, it represents warmth, gendered domesticity, and the hearth as a locus of communal bonding. Visually, the stove’s rigid geometry contrasts with the organic curves of the human form, creating dynamic tension. Its placement directly behind the central figure establishes a halo-like effect, drawing focus to her presence. By elevating a banal domestic object to a pictorial pivot, Kirchner imbues everyday life with Expressionist grandeur.

Depiction of the Female Form: Candid and Unidealized

Kirchner’s nudes are notable for their frankness. Unlike academic models, these women display naturalistic body types—soft hips, modest breasts, and unshaved underarms—rejecting the era’s narrow beauty standards. His linear outlines capture the flesh’s contours without erotic objectification; instead, the figures exude autonomy and presence. Subtle asymmetries—an arm held higher, a hip jutting slightly—enhance the sense of real bodies inhabiting real space. Kirchner’s portrayal subverts the male gaze by granting his models psychological depth: they appear in mid-thought, self-aware yet unconcerned with external judgment.

Light, Shadow, and Atmospheric Effect

Despite the strong color contrasts, Kirchner employs light sparingly. No single source is evident; instead, forms are illuminated by internal color shifts—pink highlights giving way to green or blue shadows. This flattened lighting rejects naturalistic shading in favor of a uniform, almost stage-like illumination. The stove’s glow is implied through surrounding warmth in the palette rather than direct depiction of flames. The overall effect is one of internal radiance—bodies and objects pulsing with chromatic energy rather than reflecting a cohesive external light source.

Psychological and Emotional Resonances

At its core, Nudes Standing by Stove is an exploration of human relationships and emotional states. The proximity of the figures suggests familiarity—perhaps models conversing between poses. Their varied gazes—direct, introspective, averted—create a web of interpersonal dynamics. The stove’s presence implies comfort but also confinement: the women gather close, yet the oppressive background hints at psychological weight. Kirchner captures a moment that is both intimate and slightly tense, reflecting Expressionism’s aim to surface complex inner experiences rather than external reality alone.

Relation to Kirchner’s Broader Oeuvre

Nudes Standing by Stove resonates with several of Kirchner’s key themes: the nude figure, urban interiors, and the interplay of color and line. Comparable works include Three Bathers (1909) and Girl under Japanese Umbrella (1910), where Kirchner similarly blends candid figuration with arbitrary chromatics. Yet here the domestic setting and central stove distinguish the painting, highlighting the group’s interest in communal spaces beyond city streets and cabarets. As Kirchner’s style evolved, his color palette grew increasingly acidic, and spatial flattening became more pronounced—a trajectory already visible in this 1907–08 work.

Technical Analysis and Conservation Considerations

Infrared reflectography reveals Kirchner’s pencil underdrawing, showing initial contours refined by overpainting. Pigment analysis identifies traditional natural earths and lead-based whites alongside newly available synthetic cadmiums and viridian greens—enabling the painting’s strikingly bold colors. Conservation efforts focus on stabilizing the more fugitive pinks and yellows, which can fade if exposed to harsh light. The canvas and ground remain largely intact, allowing modern viewers to experience the work’s original vibrancy and tactile brushwork.

Reception, Provenance, and Exhibition History

Initially exhibited in Berlin salons alongside other Die Brücke works, Nudes Standing by Stove attracted both acclaim and controversy. Admirers praised its daring palette and psychological depth; critics decried its departure from decorum. The painting changed hands among German collectors before entering a prominent museum collection in the 1920s. It featured prominently in postwar retrospectives on Expressionism, helping rehabilitate Kirchner’s reputation after he faced suppression during the Nazi era. Today, it is recognized as a cornerstone of early 20th-century modernism and a key testament to Kirchner’s pioneering role.

Comparative Perspectives: Expressionism and Beyond

Kirchner’s treatment of the nude diverges sharply from French Modernists like Matisse and Cézanne, who often emphasized classical balance or formal abstraction. Instead, Nudes Standing by Stove embodies a German Expressionist impulse—color as emotion, line as psychological boundary, and space as symbolic arena. Later movements, from Abstract Expressionism to Neo-Expressionism, would draw on Kirchner’s integration of figuration and gestural color. His willingness to marry candid, everyday subject matter with radical formal experimentation endures as a touchstone for artists exploring the nexus of internal states and external forms.

Legacy and Contemporary Relevance

More than a century after its creation, Nudes Standing by Stove remains profoundly resonant. Its frank portrayal of the human body, its challenge to conventional beauty standards, and its fusion of intimacy with formal intensity speak directly to contemporary dialogues around body politics, gender, and the politics of private space. Kirchner’s fearless color and inventive compositions continue to inspire painters and viewers alike, affirming Expressionism’s lasting impact on 20th- and 21st-century art. The painting invites us to reconsider the nude not as an object of desire but as a site of human connection, psychological depth, and raw artistic possibility.