Image source: wikiart.org

First Impressions: A Figure Turned Toward Silence

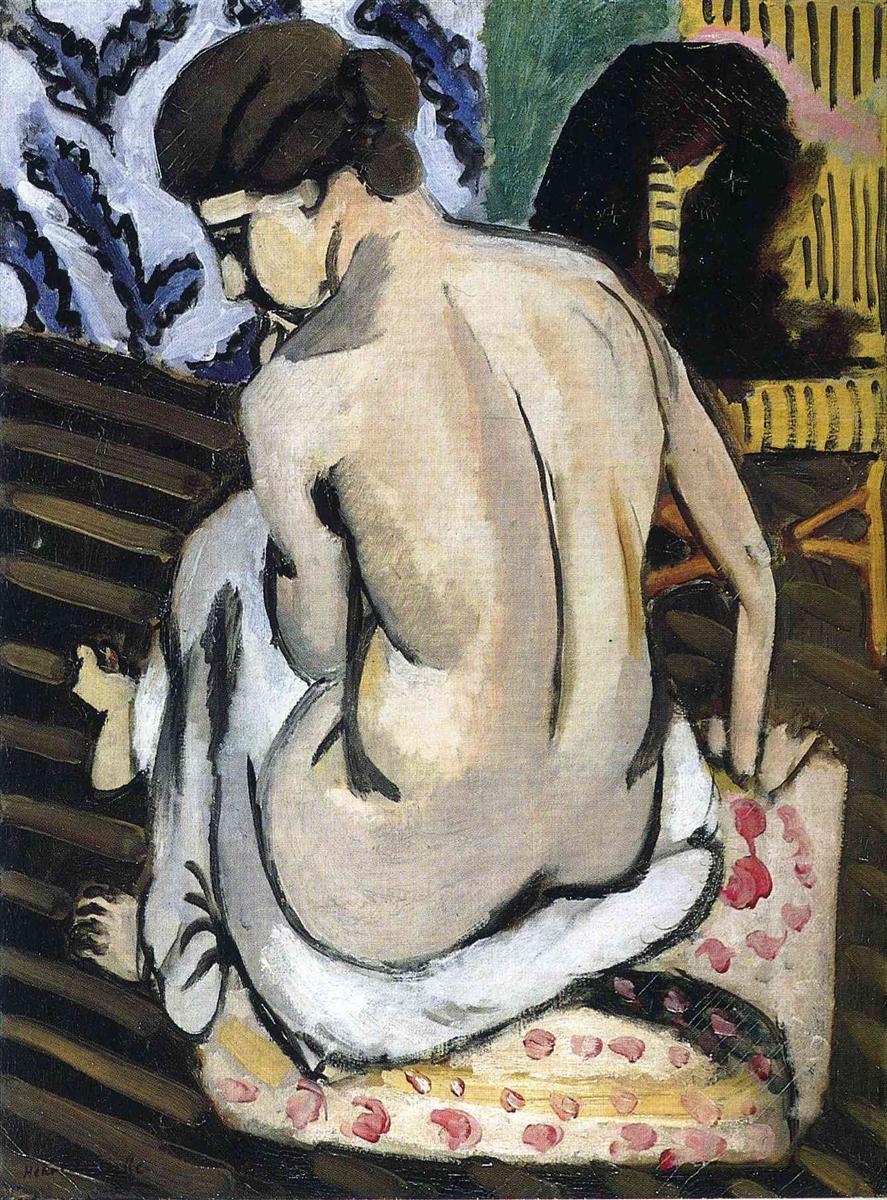

“Nude’s Back” presents a seated model viewed from behind, her body twisted slightly to the left as she gathers a drape across her hips. The pose withdraws the traditional frontal invitation of the nude and substitutes something quieter: a private, almost contemplative back, luminous against a chamber of patterned surfaces. The figure’s mass is simplified into long, supple planes that turn with temperature rather than theatrical shadow. Around her, stripes, florals, and woven textures hum in different tempos—the dark floorboards run diagonally; a dotted cushion scatters pink petals; a screen and chair at right add vertical stitches of warm yellow. The whole image reads in one breath: a human body poised within an interior that is more atmosphere than furniture, more cadence than description.

1918 and the New Grammar of the Nice Period

Dated 1918, the painting belongs to Matisse’s first season on the Côte d’Azur, when he discovered a steadier southern light and a room-bound serenity that would shape the next decade. The grammar is unmistakable. Color is tuned, not shouted. Blacks are positive pigments that anchor the chord rather than outline it. Space remains shallow yet habitable, built by overlap and temperature shifts. Pattern becomes structure, not décor. Surfaces wear the time of their making. In “Nude’s Back” that grammar is applied to one of painting’s oldest subjects with disarming restraint. The body is not a pretext for display; it is a locus where light, pattern, and calm can meet.

Composition: Spiral of Back, Cushion, and Room

The design turns on a spiral. Beginning at the small of the back, the eye climbs the vertebral ridge, rounds the shoulder blade, glides into the tucked chin and a dark band of hair, then unwinds down the arm to the drape and cushion before circling back to the hips. The room’s geometry escorts that spiral: diagonal floorboards flow beneath the thigh; the floral cushion spins the bottom edge; at the right, the cane chair and vertical screen form a stationary counterweight. On the left, a pale wall with a bold blue-and-black textile offers a cool, expanding field that prevents the composition from sealing into a closed loop. The figure sits off-center, giving the interior real agency without allowing it to commandeer attention.

The Back as Subject and Gesture

Turning the figure away changes the ethical and formal stakes. This is not a performance before the viewer; it is a moment caught within the model’s own radius. The back becomes a landscape—shoulder, rib, hip, and spine rendered as broad planes connected by elastic darks. Because the face is withheld, character is carried by posture and paint alone. The bent head, the quiet left hand near the mouth, the soft bracing of the right arm on the cushion: these gestures produce an introspective mood while allowing the painter to explore the expressive ranges of flesh without the noise of facial psychology.

Palette: Flesh, Ink, and Garden Notes

The palette is disciplined but rich. Flesh is a chord of warm ochres and cool pearly grays, with small notes of violet in the deepest turns. Blacks—sometimes brown-black, sometimes blue-black—serve as living anchors along the spine, the crease under the scapula, the under-edge of the arm, and the contour where hip meets cushion. The room supplies accents: the cushion’s pink florets, a swatch of leaf-green behind the shoulder, the yellow stripes of the screen, the honeyed caning of the chair. A white drape, neither snowy nor chalky, gathers light across the hips and falls toward the floor, its edges breathed rather than cut. The effect is maritime and domestic at once: warm inside air lit by a sea-facing window.

Black as Positive Color

Matisse’s treatment of black is central to the painting’s equilibrium. The dark seams that articulate the shoulder blade and hip are not outlines; they are notes that quicken neighboring color. Where black touches flesh, warmth blooms; where it approaches the blue-and-white textile at left, it cools and takes on the crispness of ink. Thin darks along the edges of the drape and cushion clarify form without crushing it. Even the diagonal bars of the floor read as colored structure, not negative space. In the absence of heavy chiaroscuro, these blacks supply the bass that keeps the image in tune.

Modeling by Temperature Rather than Chiaroscuro

The torso turns with temperature, not with theatrical shadow. Warm ochres gather on planes facing inward; cooler gray-violets drift into the recess under the shoulder and the shaded flank; a translucent, slightly cooler veil softens the lower back where the drape begins. The transitions are frank—brushstrokes show—but they are never clumsy. The body remains radiant because the painter resists mixing everything to a uniform middle. Light feels like climate instead of spotlight.

Pattern as Architecture of Mood

The interior’s motifs carry structural weight. The diagonal floorboards quicken the lower half, implying a gentle slope that seats the figure. The cushion’s petal-like dots produce a soft domestic counterpoint to the body’s major chords. The textile at left, with its blue-and-black arabesques on white, is painted swiftly yet persuasively; it supplies a cool vigor that keeps the flesh tones from growing syrupy. At right, the vertical stripes of screen and the cane of the chair add a measured staccato, balancing the diagonal rush of the floor. Pattern here is not ornament; it is the room’s skeleton.

Edges and Joins: Where Forms Share Air

Matisse seats each element with tailored edges. Along the shoulder, a feathered seam allows flesh to breathe into the textile. Along the hip, a firmer, darker contour declares the pressure of body against cushion. Where the drape laps the thigh, a broken line of warm and cool steps keeps the cloth alive. The left foot, half-hidden, is stated with a few small, warm notches that persuade by proportion more than detail. These joins marry simplification to credibility; the figure never looks pasted onto the interior.

Light as a Continuous Field

Rather than local beams, a continuous light suffuses the room. The back’s summit is gently bright, but nothing glares. The cushion catches warmth toward its upper edge, the floorboards shine along their long strokes as if polished by use, and the textile throws a cool reflection into the left shoulder. Everything relates to the window’s implied presence beyond the frame. The painting therefore reads as a portion of a day—air moving through pattern—rather than an arranged tableau.

The Ethics of Distance and the Humanity of the Pose

By showing a back and averted head, Matisse refuses the conventional pact between viewer and nude. What remains is not coyness but dignity. The model rests in her own weather; the painter attends without trespass. The nude is thus reclaimed from anecdote and returned to presence. This stance—a mixture of intimacy and reserve—runs through Matisse’s Nice-period figures and helps explain their durable freshness.

Dialogues with Tradition without Quotation

The painting quietly converses with precedent. The back-as-landscape recalls Ingres’s lucid surfaces while avoiding his porcelain finish; the domestic setting brings to mind Degas’s bathers, but Matisse trims narrative down to climate and relation; the decorative surround nods to the odalisque tradition without chain or harem fantasy. The synthesis is wholly his: classical clarity stripped of academic polish, decorative intelligence harnessed to calm.

Space Kept Close to the Plane

Depth is credible but shallow. Overlap does the work—arm over thigh, drape over hip, cushion under body, chair behind—and value steps nudge distance where needed. The floor’s diagonals tilt the figure toward us while the vertical screen pulls the eye back into a gentle pocket. Because space clings to the plane, the painting reads instantly as designed surface and only then as a room. This closeness gives the image its modern poise; it lives happily next to photography and graphic design without becoming graphic itself.

Brushwork and the Pace of Making

The surface records different tempos. Flesh is built with medium-length, directional strokes that follow musculature and bone. The drape is churned in softer, circular passes, with thicker ridges where the cloth gathers. The cushion’s petals are dabs pressed once and left, their modest impasto catching light. The floorboards are long, unfussy drags that leave the canvas’s tooth visible between strokes, creating a vibration that reads as sheen. Nothing is buffed into anonymity. The painting breathes because its making breathes.

Rhythm: Diagonal, Curve, Vertical

Three rhythmic families organize the eye. The diagonals of the floor accelerate the bottom third; the long curves of the back and arm slow the middle; the verticals of screen and chair stabilize the right edge. Move through the picture and these tempos interlock, like parts in chamber music. The result is not a static still life of body and props, but a quiet choreography.

Relation to the Odalisques and to Sister Works of 1918

Within the constellation of 1918 works, “Nude’s Back” is a hinge. Compared with “Half Lying Nude,” it is more introspective and less staged; compared with balcony portraits, it turns away from the Mediterranean band and looks inward to pattern and wood. It anticipates the odalisque years, where printed fabrics and cane furniture become abundant, yet it retains a lean economy. Patterns support presence rather than perform it. As a group, these works announce the Nice vocabulary: thresholds, tuned palettes, positive blacks, and a surface that reveals its own decisions.

Guided Close Looking: A Slow Circuit

Begin at the small of the back and travel up the vertebral ridge, noticing how a bluish gray cools the turn under the shoulder blade. Slide into the hairline, where a few darker strokes tidy the bun; catch the thin warm note at the nape that warms the head into the body. Drift down the inside of the right arm, watching the dark seam sharpen as it nears the elbow, then soften into the wrist. Pause at the cushion: pink petals differ in size and direction, proof that repetition needn’t be mechanical. Move left across the drape where warm and cool whites braid together. Let the diagonal boards carry you to the left foot—two or three strokes only, yet completely persuasive—before you climb back into the cool textile and then return, naturally, to the back’s long curve. With each loop the painting converts from inventory to cadence.

Material Evidence and the Courage to Stop

Small pentimenti survive. A restated contour thins the waist; a second pass of black fortifies the shoulder cleft; a patch of blue-white reclaimed in the left textile opens space behind the head; the line of the floor nearest the viewer is reinforced to quiet an earlier, more agitated sweep. Matisse does not erase these decisions. He halts when relations feel inevitable, not when surfaces are cosmetically smooth. That earned inevitability is the quiet authority we feel.

Lessons Embedded in the Canvas

For painters and designers, the work is a compact manual. Build volume with temperature and a few decisive darks. Let pattern shoulder structural tasks instead of piling on detail. Vary edge quality to seat forms in shared air. Keep depth close to the plane so the image reads at a glance. Allow brushwork to announce the time of its making; truth of process is a kind of light. Above all, trust the simplest relations—curve against stripe, warm flesh against cool textile, black seams against pearly planes—to carry feeling more faithfully than elaboration.

Why the Image Still Looks New

A century on, “Nude’s Back” aligns with contemporary seeing. Big shapes register immediately; color is sophisticated without ostentation; process remains visible and honest; the sitter retains privacy in a way that anticipates modern sensibilities. The figure’s back, once merely a prelude to frontality, becomes sufficient subject. The painting’s calm arises from design rather than decorum, from relations that feel necessary rather than effects that ask to be admired.

Conclusion: Presence Turned Inward, Light Turned Outward

“Nude’s Back” reveals how little is needed to sustain a human presence in paint: a handful of tuned colors, a few living blacks, edges that breathe, patterns that serve, and a light understood as climate. By turning the figure away and letting the room’s rhythms cradle her, Matisse composes a modern, humane nude—neither myth nor spectacle, but a person momentarily at rest within air. The painting is companionable: it steadies the eye and clarifies attention, reminding us that intimacy in art is less a matter of exposure than of relation.