Image source: wikiart.org

First Impressions: A Nude Composed from Air, Line, and Tempered Light

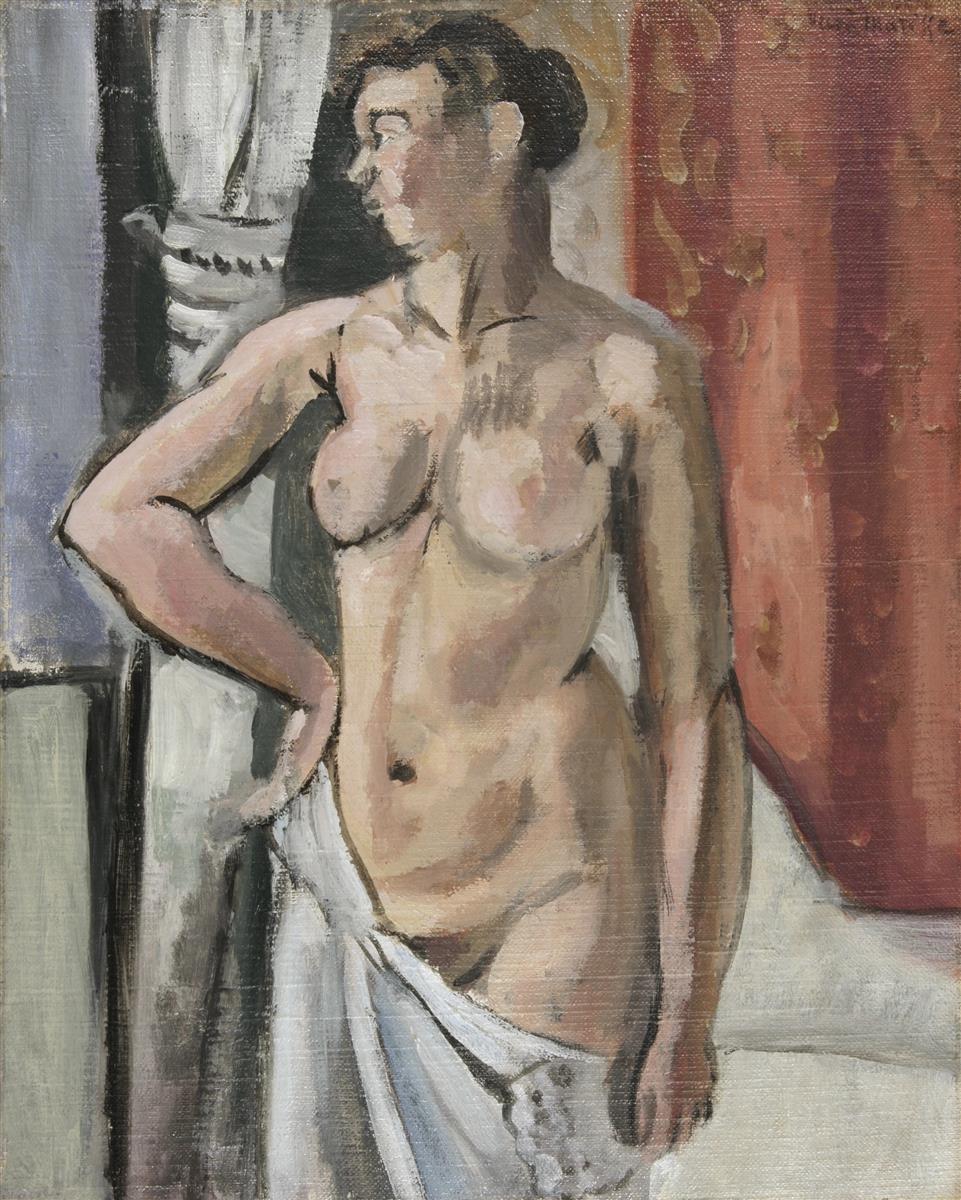

Henri Matisse’s “Nude with Drape” (1919) is a compact masterclass in how to make a familiar subject feel newly seen. The figure stands three-quarter length, head turned left, one hand planted at the hip like a column capital and the other released along the thigh where a white cloth gathers and falls. Behind her, a pared interior—cool greys to the left, a warm ornamental red to the right—creates a shallow stage that holds the body close to the surface. Light arrives as a gentle climate rather than a theatrical beam, softening transitions and letting the body’s planes breathe. A few decisive dark seams and a handful of warm and cool notes are enough to build a form that is palpable, poised, and unlabored. The picture reads at once as observation and as design, a nude and an arrangement of relations, which is exactly the balance Matisse sought after the upheavals of the 1910s.

Nice-Period Context: A Pivot from Bravado to Poise

Dated 1919, the painting belongs to the early years of Matisse’s Nice period. In these canvases he traded the jagged dissonances of his prewar experiments for harmonies of clear structure, breathable color, and sustained light. Nice offered him rooms filled with steady Mediterranean brightness and models who could be staged with fabrics and shutters and screens. “Nude with Drape” distills that environment to essentials: a body, a fold of cloth, a neutral column, a red hanging. The goal is not narrative or allegory; it is the creation of what Matisse called “a harmony parallel to nature,” in which the sensation of living form is achieved through ordered relations of tone, temperature, edge, and rhythm.

Composition: A Shallow Stage Framed by Column and Curtain

The composition is direct and calculated. On the left, a whitish column and the hint of a draped curtain introduce vertical stability and cool light; on the right, a red patterned hanging supplies warmth, weight, and a faint whisper of luxury. The nude stands between these architectural bookends like a living pilaster. Her torso forms a flattened S-curve: shoulder to breast to belly to hip, a rhythm that counterpoints the straightness of the column and the drop of the curtain. Matisse places the figure up close, cropping the head high and the legs low so that the viewer feels nearly level with the torso. Depth is shallow—more relief than recess—and that shallowness keeps design and sensation joined. Every element participates in the body’s stature.

The Body as Architecture: Planes, Axes, and Load-Bearing Curves

Matisse constructs the figure as if building a small piece of architecture. The head turns, creating a rotational axis that runs through neck and sternum; the planted left arm forms a buttress; the right arm, relaxed, is a counterweight. The torso is not modeled by laborious gradations but by clear planes that tip gently in the light. One feels the ribcage as a buoyant oval, the abdomen as a softer plate; the clavicles read as a lintel under which the throat sits like a shallow niche. The belly button and the slight crease at the waist are not details for their own sake; they are signposts that keep the harmony of masses legible. This clarity is not chilly. The warm, breathable half-tones let the body stay alive while remaining structurally intelligible.

Drawing with the Brush: The Role of the Dark Seam

What many viewers read as “outline” in Matisse is better described as a living seam laid with the brush. Along the shoulder, under the breast, down the flank, the painter lets a supple dark line thicken and thin, binding adjacent tones and tightening forms without imprisoning them. These seams act like musical bass notes: they set tempo and key for the lighter passages to play against. Around the hand that rests on the hip, short decisive darks carve knuckles and wrist; around the face, a few notches under brow and nose settle the head into its turn. Drawing and painting are one operation here. The seam is both contour and color, both description and rhythm.

Palette and Climate Light: Warm Flesh, Cool Grounds, and One Red Banner

Color is intentional and spare. Flesh carries warm greys and pale terra-cottas tempered by cool cools at the jaw, underarm, and inner thigh. The left half of the background is a range of silvers and dove-greys that suggests stone and fabric; the right half, dominated by the red hanging, keeps the composition from draining of blood. White—the drape, hints of bedding, the column’s highlight—does not shout; it is veiled and tuned to the same climate light that bathes the body. There is little pure black; Matisse prefers near-blacks that can shift warmer or cooler as context requires. Because everything is keyed to the same atmosphere, transitions feel inevitable rather than forced.

Surface and Process: The Time of Making Left Visible

The canvas shows its weave through semi-opaque layers; this is not a glazed, polished surface. Matisse wants you to see decisions. A plane on the ribcage is restated with a slightly cooler stroke; the red hanging contains scrapes and scumbles where a former value peeks through; the white drape is dragged so thin over the linen that texture becomes part of the light. This visibility of process fosters intimacy: viewers are invited not only to see the model but to follow the painter’s path of looking—where he hesitated, where he committed, where he simplified.

The Drape: Modesty, Movement, and Measure

The white cloth is modesty and metronome. It sets off the flesh, marking temperature contrast and texture change. Its edge, held lightly in the right hand, gives the figure a second rhythm: a diagonal fall that answers the torso’s S-curve and the curtain’s vertical drop. The cloth also calibrates value. Its near-whiteness makes the body’s warm half-tones glow without resorting to saturated pigment; it gives the red hanging a partner across the composition; and it locates the lower register of the picture’s light, so the viewer can read form without dramatic cast shadows. In classical painting, drapery often performs narrative work; here it measures the music.

Tradition Reimagined: From Ingres and Titian to a Modern Nude

“Nude with Drape” belongs to a lineage of standing nudes whose lineage stretches from antiquity through Titian, Giorgione, and Ingres. Yet it is unmistakably modern. Matisse flattens and simplifies, keeps depth close to the plane, and lets black act as a color among colors. The head’s almost masklike abbreviation recalls Ingres’s disciplined drawing, but the body’s construction by planar patches owes more to Cézanne’s architecture of sensation. Above all, the painting suspends anecdote. There is no myth attached, no story to decode. The model is a person, the body a living structure, the room a device for harmony.

Space, Cropping, and the Viewer’s Position

The cropping is bold. The head grazes the upper edge; the lower body is cut mid-thigh; the left elbow presses toward the picture’s margin; and the right forearm descends into the drape where the hand almost disappears into light. This framing denies the viewer the usual comfortable distance. We stand at the model’s height, close enough to feel the air cool on the left and warm on the right. The spatial shallowness makes the painting read as both interior and relief sculpture, connecting it to Matisse’s sculptural practice where volume is discovered by contour and plane rather than by deep recess.

Gesture and Psychology Without Anecdote

The model’s posture—head turned away, hand at hip, torso flexed—communicates a self-contained alertness. There is no theatrical expression; the face is quiet, almost withheld, so that character must be read through stance. The planted hand asserts, the turned head listens, the set of the shoulders steadies. The nudity is candid but not exhibitionistic. Because drapery, column, and curtain are stripped of descriptive fuss, they function as psychological supports: the column for self-possession, the red for warmth and intimacy, the cloth for modest control. Matisse grants the model dignity by refusing to editorialize her body.

Kinships and Foreshadowing: From 1919 to the Odalisques

Placed beside Matisse’s early Nice interiors and his contemporaneous nudes, this picture sits on a path that leads to the odalisques of the 1920s. Those later canvases will indulge pattern, color, and Orientalist décor; “Nude with Drape” keeps décor on a leash while already exploring how a figure converses with textiles and surfaces. The red hanging here is a seed of the later patterned screens; the swift seams around breast and flank look forward to the calligraphic contours of the odalisques; the climate light is already fully in place. Yet the restraint of 1919 gives this painting a clarity that some of the later luxuriant works trade for splendor.

The Discipline of Economy: Saying More with Less

Economy is the picture’s ethics. The model’s left breast is constructed with two or three directional strokes that infer volume and skin without fuss. The belly button, a mere comma, is enough to pivot the abdominal planes. The face turns with a handful of notations: a shadow along the jaw, a cool in the eye socket, a quick mark at the nostril. Even the red hanging receives only what it needs—soft patterning to suggest brocade, then stop. Economy is not minimalism for its own sake; it is trust that the viewer’s eye, given right relations, will complete the rest. This trust creates intimacy between painter and viewer, and it keeps the painting light on its feet.

Light as a Unifying Climate

Rather than carve the body with dramatic highlights and deep shadows, Matisse lets a pervasive light bind the room. The column’s cool white reflects into the left shoulder; the red hanging warms the right flank; the bed or platform under the figure diffuses light upward into the drape. Because the whole field shares one climate, the nude feels at home in the room, not pasted against it. This unification is one of the Nice period’s great gifts to modern painting: a way to maintain modern flatness while wrapping forms in believable light.

Close Looking: A Suggested Path Through the Picture

Begin at the turn of the head, where a cool stroke under the brow and a soft notch at the nose set the profile’s tilt. Travel down the sternum to the small darker cross-hatching of clavicles, then outward along the planted arm whose contour thickens and thins like breath. Swing across the ribcage, let the paint’s direction indicate swelling and release, and drop to the small comma of navel that anchors the torso’s center. Follow the drape’s cool fall to the lower edge, noticing where linen weave emerges through thin white. Climb back through the relaxed right hand—little more than warm and cool blocks—and let the red hanging’s pattern return you to the face. After a circuit or two, the painting’s rhythm becomes bodily; you breathe with the figure.

What the Painting Teaches About Making Images

“Nude with Drape” offers practical lessons useful beyond painting nudes. Build forms from a few comprehensible planes; lean on temperature and value shifts rather than hard edges; treat dark as an active color, not a mere outline; choose one warm and one cool anchor in the background to steady the figure; and allow process to remain visible so that viewers can enter the work through its making. Most of all, compose for a viewer’s path—give the eye a circuit that returns to the figure’s center, then let local surprises keep the journey fresh.

Conclusion: A Modern Classic of Poise

Matisse’s 1919 nude demonstrates how modern painting can honor tradition without becoming derivative. The model is not mythic, yet the pose carries the gravity of long history; the room is not lavish, yet it frames the body with dignity; color is modest, yet light suffuses everything with life. With a handful of tuned relations—column and curtain, warm and cool, seam and plane—Matisse fashions a figure that stands in quiet authority. The painting offers what the artist most prized: an equilibrium where looking becomes a form of well-being.