Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

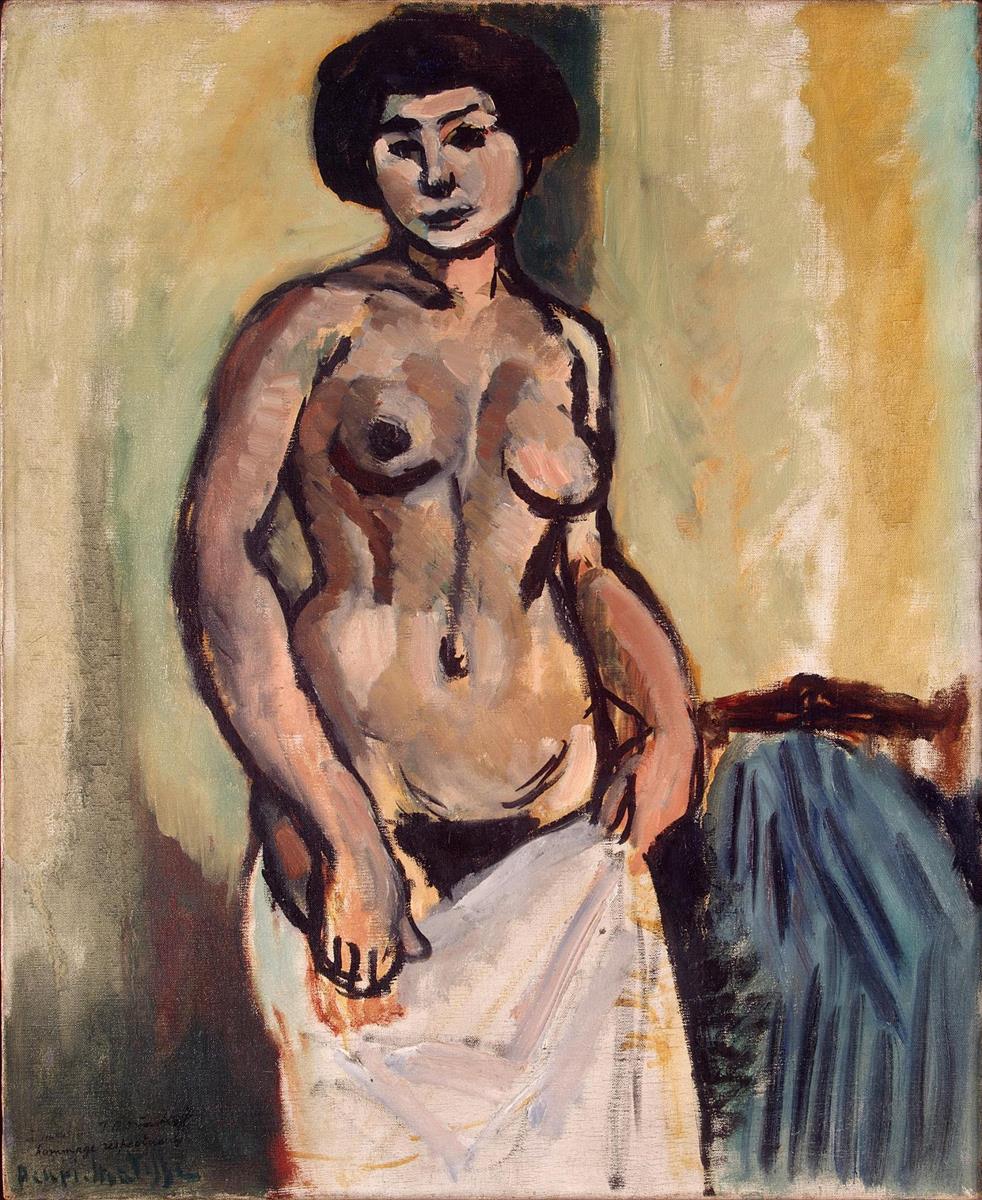

Henri Matisse’s Nude, Study (1908) presents a standing figure in a sparse interior, painted with firm black contours and planes of warm, earthy color. The model gazes outward with a mask-like reserve, one hand loosely gripping a white drapery that slips across the hips. A strip of teal cloth falls over the chair rail at the right; behind her, the wall is divided into vertical bands of pale green, cream, and ocher. What first reads as an uncomplicated studio pose quickly becomes a compact demonstration of Matisse’s 1908 ambitions: to reconcile the audacity of Fauvist color with an increasingly sculptural sense of form, to simplify without thinning, and to build human presence from decisive strokes rather than accumulated detail.

Historical Context

The year 1908 sits at a hinge in Matisse’s development. After the headline-making blaze of Fauvism in 1905–06, he slowed the chromatic fireworks and pursued a steadier grammar of planes, edges, and limited palettes. At the same time he was working seriously in sculpture, paring the figure into volumes and profiles that would inform his painting. Nude, Study belongs to this moment of consolidation. It carries the memory of Fauvist heat—ocher, coral, and teal glow against the pale wall—but temperance is the rule. The brush speaks with deliberate economy; color is structural, not simply expressive; and the figure’s weight, balance, and gesture are more important than anecdote. As European art pivoted toward new modernisms in 1907–08, Matisse’s answer was neither fracture nor pastiche, but an equilibrium between sensation and clarity.

Composition and Pose

Matisse favors a frontal three-quarter pose that grants the figure stature without theatricality. The torso, slightly twisted, sets up a sequence of diagonals that enliven the rectangle: the left arm descends almost vertically, the right arm angles gently as it gathers the cloth, and the drapery itself forms a white triangular plane that counters the softer curves of abdomen and thigh. The head tilts a degree toward the left shoulder, introducing a quiet asymmetry. A chair back peeks in at the right, its dark rail marking a shallow depth and supporting the teal garment that cascades like a cool waterfall. The composition breathes because Matisse leaves generous air around the body; the figure does not crowd the frame, yet her presence occupies it fully.

Palette and Color Strategy

The palette is restrained compared to the riotous Fauvist landscapes, but it remains emphatically non-naturalistic. Flesh is built from a mosaic of ochers, warm pinks, russets, gray-violets, and olive green shadows, all bound by confident black lines. The wall is not a single hue but a softly brushed sequence of vertical bands—greenish gray near the left edge, pale cream at center, warm yellow-ocher at the right—so that color replaces perspectival devices to create space. A teal garment over the chair acts as a cool anchor that keeps the composition from overheating. White is never pure; it is modulated with lilac and ivory within the drapery, a reminder that light is a color decision rather than an academic highlight. The effect is a quiet orchestration: warmth advances, cool retreats, and the figure locks to the background through calibrated contrasts.

Contour and Drawing

Dark contour is the painting’s structural armature. Matisse draws with the brush in sweeping, unhesitating lines that decide the body’s limits and internal rhythms. The outline around the shoulder and breast swells and thins with the form; the knuckles of the left hand are not described with small marks but inferred by a single, bent stroke; the jaw and cheekbone are stated as an assertive arc that sets the entire head. These lines behave like the lead in stained glass: they separate color fields while making them glow. Because the contour is so clear, the interior modeling can remain minimal; planes of flesh read as volumes not through careful blending but through adjacency and the direction of the brush.

Brushwork and Surface

Matisse’s brushwork keeps the making visible. The wall’s vertical fields are laid in with broad, semi-transparent passes that let the weave of the canvas breathe through, producing a soft granularity that feels like light diffusing across plaster. In the figure, strokes follow the anatomy’s turn—the length of the forearm, the sweep of the rib cage—so that touch and structure align. Edges are often left slightly open where two colors meet, a small halo that keeps the image alive and prevents flatness from becoming deadness. The drapery is blocked with quick, angled swathes that indicate fold and weight without fetishizing cloth; you register its coolness and gravity more than its weave. Everything speaks in the same pictorial voice: concise, visible decisions.

Light and Space

Rather than binding the scene to a single directional light, Matisse bathes it in a generalized illumination created by color relationships. The figure feels round because warm planes abut cooler ones; the wall recedes because its bands shift in temperature and value; the white cloth projects because its pale plane is cut by the dark of the pubic triangle and the contour of the thigh. Depth is shallow and calm. The chair rail at the right supplies the painting’s main horizontal marker and suggests a studio corner without building a perspectival box. Space becomes an envelope rather than a measured chamber, allowing the viewer to stay close to the surface while believing in the figure’s weight.

Gesture and Psychology

The model’s gesture is simple, almost ceremonial: one hand relaxed at her side, the other gathering the cloth across her hips. The head tilts, eyes darkly ringed, mouth set in a neutral line. Because the face is rendered as a mask of planes and shadows rather than as a portrait, psychology radiates from posture rather than expression. She reads as self-possessed, neither coy nor confrontational. The loosely held drapery denies the narrative of undressing or seduction; it is a painter’s prop that establishes tone and emphasizes the contrast between crisp white and warm flesh. The painting offers a respectful gaze: the body as an intelligent structure in space, not a spectacle.

The Face as Mask

Matisse’s faces from this period often carry a mask-like clarity, and this study is no exception. Dark lines ring the eyes and carve the nose; the lips are a small, shadowy wedge; the hair is a solid mass that frames the face like a helmet. This treatment, influenced by his interest in non-Western sculpture and medieval icons, is not dehumanizing; it concentrates attention. By reducing facial detail, Matisse asks the viewer to read the whole body for meaning—the lift of the shoulder, the tension in the fingers, the weight settled in the hips. The mask steadies the mood and helps the figure hold the picture plane without dissolving into anecdote.

The Vertical Bands of the Background

The divided wall is not a mere backdrop. Its bands of green, cream, and yellow operate like a painted architecture, giving the figure three different atmospheres to inhabit at once. On the left, the greenish field cools the left shoulder and creates a soft silhouette. At center, the pale band illuminates the sternum and belly, allowing warm and cool strokes to play across the flesh. At right, the deep ocher picks up and warms the arm and side. These verticals also echo the figure’s upright stance; they emphasize that the picture is built from large, simple planes rather than a scatter of details.

Hands, Drapery, and the Language of Touch

Hands in Matisse are often summarized rather than parsed. The left hand here is a cluster of hooked marks that nevertheless conveys weight and rest. The right hand, gripping the cloth, is abbreviated to a dark shape with a few incisive edges. The drapery falls in triangular segments, each a single stroke turning at the edge. This economy allows touch to speak: you feel the slight tension in the fingers, the drag of fabric across the thigh, the stillness of the left hand at the hip. The tactile reality of these simplified forms contributes as much to the painting’s believability as any facial likeness could.

Relationship to Sculpture

Matisse’s concurrent sculptural practice is audible everywhere. The planes of the torso turn decisively; the breast reads as a single, rounded facet; the abdomen is a shallow basin bounded by firm edges; the left thigh is cut from a long, clear arc. The painter treats the figure as a sequence of forms to be joined rather than as a patchwork of local details. This sculptural grammar—volume articulated by abrupt shifts of plane—lends dignity and permanence to the figure while keeping the surface frank and modern.

The Model and the Studio

Although anonymous, the model is not generic. Her broad jaw, dense hair, and compact build give her specificity and weight. The setting is unmistakably a studio: a chair, a blank wall, a length of cloth. Matisse uses this unadorned space to focus attention on pictorial problems—balance, color temperature, contour—rather than on narrative. The sparseness is a virtue. It lets the viewer attend to how the body stands, how the planes meet, and how color does the heavy lifting of light.

After Fauvism: A New Equilibrium

Compared with the ferocious contrasts of 1905–06, Nude, Study signals a move toward orchestration. Color is strong but moderated; tonal steps are few but carefully placed; drawing is assertive but not aggressive. This equilibrium would lead directly to the great interiors of the next decade, where color fields become architecture and figures inhabit rooms defined by hue rather than by architectural detail. In this sense the painting is both an endpoint and a starting point, harvesting Fauvism’s lessons while planting seeds for Matisse’s mature classicism.

The Viewer’s Gaze

The painting manages the gaze without defensiveness. The model looks outward, but the dark mask of the features and the calm set of the body refuse the invitation to voyeurism. The cropping is respectful; the figure fills the frame but does not spill out of it. The white drapery is not strategically placed to titillate but to create a cool plane that anchors the composition. You are asked to look with the same composure with which the figure stands, to measure intervals of color and weight rather than to chase anecdotal meaning.

Materiality and Scale

Seen up close, the painting rewards attention to the physical work: ridges along a contour where the brush slowed, scant patches where underpaint glows through, a quick correction at the shoulder that leaves a ghost line. From a step back, these traces consolidate into clarity; the planes lock, the wall breathes, the drapery holds its angle. The scale is intimate enough to feel like studio distance and large enough for the figure to claim monumentality. Matisse calibrates the painting for both experiences: tactile when near, architectural when far.

Comparisons within the Oeuvre

Placed beside Nude Study and Nude Wearing Red Shoes from 1907, this 1908 canvas keeps the sculptural gravity but allows slightly more light into the room. It is less theatrical than the North African-inflected Blue Nude and closer in spirit to the quiet interiors that will culminate in The Red Studio. Its restraining of palette, reliance on contour, and consistent brush language make it a touchstone for understanding how Matisse transforms the figure into a modern structure without sacrificing warmth.

Legacy and Continuing Relevance

Nude, Study remains instructive because it shows how little is required to make a figure present. A handful of hues, a handful of strokes, and a handful of lines are enough—provided they are tuned with conviction. The painting models an ethics of clarity: respect for the surface, for the body’s architecture, and for the viewer’s time. It also models a path for contemporary painters seeking poise between expressive color and structural drawing. The lessons are portable: let color do the lighting, let contour dignify form, and let simplification carry emotion.

Conclusion

Henri Matisse’s Nude, Study is a poised meditation on the modern nude. The figure stands in a shallow studio of color bands, her body articulated by strong contour and sparse, truthful planes. The white drapery and teal cloth provide cool counterpoints to the warmth of flesh; the background builds space without perspective; the face, rendered as a mask, steadies the mood. Painted in 1908, the work condenses Matisse’s pivot from Fauvist blaze to sculptural clarity. It is both intimate and monumental, frank and tender, and it demonstrates with uncommon economy how painting can construct human presence from color, line, and touch alone.