Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

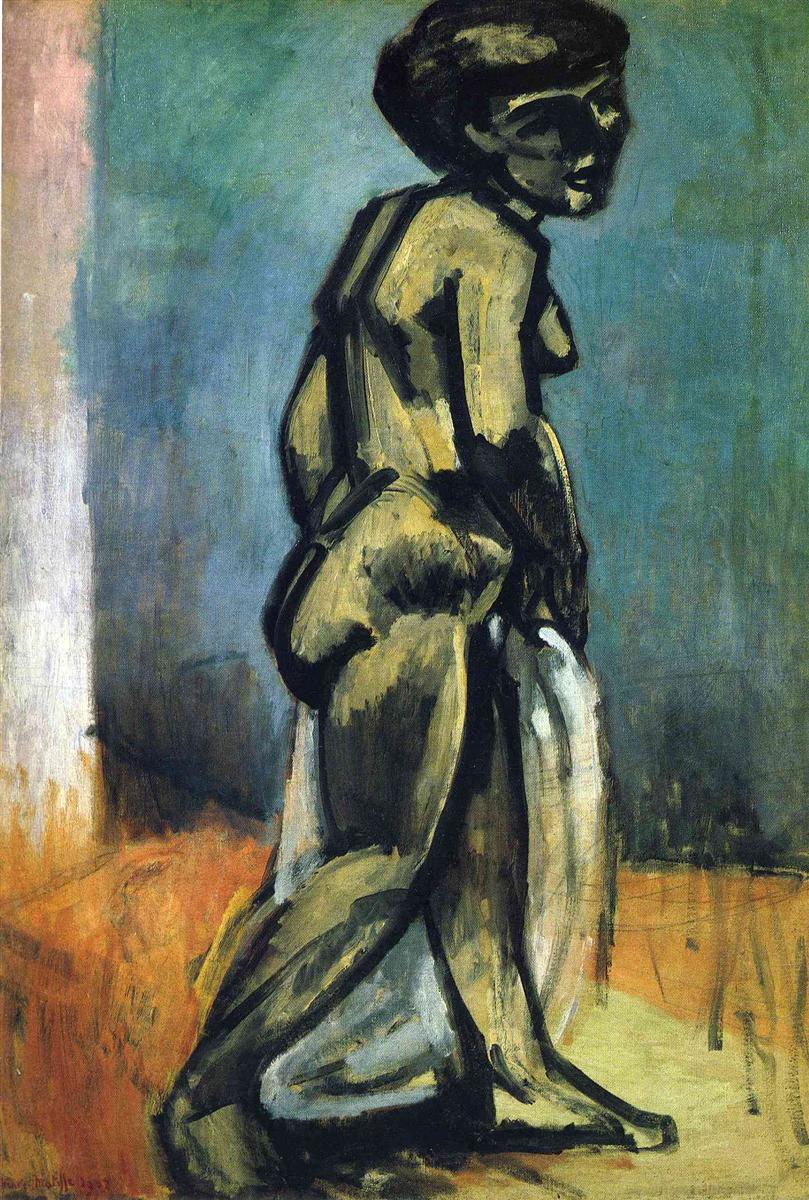

Henri Matisse’s Nude Study (1907) captures a decisive moment in the artist’s evolution from the blazing chroma of early Fauvism toward a more sculptural, architectonic modernism. A single figure, rendered in powerful planes of color and encircled by assertive black contours, stands against a compressed field of teal-blue and earthen orange. The pose is transitional and charged: the model turns in three-quarter view, weight settling into the legs as a white drapery slips along the hip and thigh. Rather than aiming for descriptive likeness, Matisse uses the nude as a laboratory for structure, rhythm, and light. What results is not a classical ideal but a modern monument—an image of the body built from decisive drawing, concentrated palette, and the grain of the brush.

Historical Context

The year 1907 is a hinge in European art and in Matisse’s career. Two years after the shock of Fauvism, he had begun tempering coloristic exuberance with a renewed interest in weight, contour, and simplified geometry. Across Paris, artists were revisiting the figure with an eye to essential form, drawing inspiration from sculpture, so-called “primitive” masks, and the architectonic logic of Cézanne. Nude Study emerges from this ferment. It holds on to the Fauvist conviction that color can carry structure, yet it pushes toward a body conceived as volumes bound by line. The canvas reads not as a preparatory note but as a statement: the expressive power of the nude resides less in mimetic detail than in the orchestration of planes.

Subject, Pose, and Presence

The model stands turned to the right, head pivoting back toward the viewer. The body feels newly assembled—shoulder, hip, thigh, and calf articulated as blocks and arcs that fit together like carved forms. The stance evokes contrapposto without theatrics, distributing weight so that one leg anchors while the other advances. A cloth gathers along the hand and thigh, functioning less as narrative prop than as a cool counterplane against warm flesh. The face is simplified to mask-like shadows and highlights, sufficient to declare attention without diverting the eye from the body’s structural music. Presence here is the result of balance: torsion in the trunk, steadiness in the legs, and a head that turns just enough to complete the spiral.

Composition and Spatial Design

Matisse composes the figure as a vertical column slightly off center, allowing space for the turn of torso and drapery. The stage is shallow: a wedge of ocher ground rises toward a wall of teal-blue that fades to a pale, chalky vertical at left. These fields are not scenery; they are planes against which the body reads. The limits of the canvas act like architectural edges, pressing the model forward. There is no perspectival chamber, no chair or curtain to anchor the scene. Instead, space is a compressed envelope whose shifting hues imply depth in the simplest terms. The eye is forced to live with the figure—its edges, mass, and rhythm—rather than to wander elsewhere.

Palette and the Architecture of Light

The palette is concentrated and purposeful. Warm ochers and olive flesh tones meet cool greys and blue-greens; black contour locks them together. The body’s illumination is not built by soft chiaroscuro but by the adjacency of hues: cool shadow planes push against warm lit planes, and sudden pockets of darkness—at the neck, under the breast, along the thigh—provide emphatic punctuation. The background’s teal-blue bathes the figure in a generalized atmosphere, while the earthen floor lifts warmth from below. In several passages, Matisse allows thin paint to breathe, so that the canvas weave and undercolor become part of the light. The effect is both raw and controlled, like sun angling through a studio and finding the shape more than the detail.

Contour and the Ethics of Line

The painting’s authority rests on contour. Black lines, broad and elastic, encircle the major forms and decide their weight. These are not tentative corrections; they are declarative strokes that translate observation into structure. The shoulder’s arc, the hip’s bulge, the shins’ sweep—each is assigned an edge that carries the measure of the form. Where line thins or breaks, the eye fills the interval, participating in the building of the body. In 1907 Matisse trusted line as a moral premise: clarity beats illusion. The contour is not a cage for color but a partner that grants the planes dignity and calm.

Brushwork and Surface

The surface is frank about its making. Long, directional strokes block the background, shifting from scumbled blue-green to a pale vertical that reads as light bouncing off a wall or curtain. The flesh is laid in with broader swathes that follow the turn of limbs and the swell of muscle. Dry-brushed ridges catch on the canvas tooth, leaving a weathered texture that feels appropriate to a study concerned with bones and volumes. In places, the brush drags pigment so thinly that underlayers flare through like breaths of air. These material traces are not incidental; they keep the image alive, reminding the viewer that the figure is an accumulation of decisions made at speed.

Dialogue with Sculpture

Few Matisse paintings are more openly sculptural. The figure seems carved rather than painted, as if a block had been cut into shoulders, buttock, and thigh with broad, confident blows. The simplified facial planes and the helmet of dark hair recall studio encounters with classical casts and with non-Western sculpture that prized essential shape over surface texture. The model’s volume is not modeled by infinite tonal steps but by sharp transitions between planes of color, much as a sculptor would make a cheek by turning a single plane rather than by stippling pores. This dialogue with sculpture is crucial: it is how Matisse transforms a living body into a durable, modern form.

The Nude as Modern Archetype

Nudes had long served as the proving ground for painters’ skill. Nude Study redefines that ground. Instead of offering an idealized marvel of anatomy or an anecdotal studio scene, Matisse presents the body as a contemporary archetype—timeless, unadorned, and built from essentials. The sheet introduces the faintest whisper of narrative, but it does not shift the focus from structure. There is no coyness and no erotic display; the genitals are present but unaccented, the pubic shadow no darker than those under the chin or knee. The painting’s eroticism, if it has one, resides in the sensual assurance of planes fitting together, in the pleasure of contours finding their path.

Gesture, Tension, and Poise

The pose contains a compressed energy. The turn of the head back toward the viewer tightens the neck muscles; the hand that gathers the drapery activates the forearm; the thigh that steps forward presses into the ground with measurable weight. These tensions do not explode; they resolve into poise. The viewer senses a before and an after—the model settling into position, the model about to shift—and the picture catches the interval between. In this respect the painting has the temporal quality of a rehearsal, a body finding its balance under the painter’s gaze.

Background as Stage and Atmosphere

Matisse’s backgrounds from this period often function as abstract stages: large color fields that create mood and define space without describing objects. Here the teal expanse serves as a cool envelope that makes the warm body advance, while the burnt orange ground supplies a heat that rises and licks the lower limbs. A pale vertical at left acts like a reflected shaft of light, or the edge of a wall or curtain, though it remains ambiguous enough to resist being an object. These planes are not neutral. They collaborate with the figure to build the painting’s architecture, determining where the eye settles and how the body’s edges register.

Process, Pentimenti, and the Value of the Study

The word “study” can mislead. Rather than implying an unfinished fragment, it names a mode of working where essentials are prioritized. In Nude Study, traces of change—slipping lines at the calf, a ghost of contour around the hand—testify to the search for exact placement. The spareness sharpens attention: without elaborate detail the viewer reads the big decisions—where weight sits, how mass turns, where light collects—with uncommon clarity. The painting is both an endpoint and a tool, a statement in its own right and a pathfinder for later nudes in which pattern, color, and pose would grow more complex.

Relation to the 1907 Moment

The broader art of 1907 was pushing the figure to extremes—toward fracture in some quarters, toward primitivist reduction in others. Matisse’s answer is poised at the center: simplify to essentials, build weight with contour, let color fields carry space. Nude Study aligns with this ethos. The head’s mask-like treatment and the emphatic black lines acknowledge global sources without quotation; the flat planes of background reject Renaissance depth without severing ties to the body’s reality. Modernity here is not a rejection of the nude but a re-grounding, a return to the body as a composed set of relations.

Anticipations and Echoes

Several features anticipate Matisse’s later achievements. The reliance on a limited palette foreshadows interiors where cool walls and warm figures create luminous equilibrium. The willingness to let line dominate points toward his paper cut-outs, where contour alone must define form. The sculptural conviction in the body prepares the way for the monumental odalisques and seated nudes of the 1920s and 1930s. At the same time, the painting echoes backward to Cézanne’s bathers in its confidence that planes can build flesh, and to Matisse’s own early Fauvist canvases in its belief that color is not decoration but structure.

Materiality, Scale, and Viewer Distance

The painting’s scale encourages close looking. From a step away, the heavy black lines are not uniform; they feather, pool, and break at corners where the brush changed direction. The ocher ground reveals scrapes and returns, places where the artist reconsidered the edge. The teal field varies in saturation, an atmospheric modulation that prevents flatness from becoming monotony. This material presence matters because it calls the viewer into the making. You see not only a body but also the actions that called it forth—lays, cuts, scrubs, and glazes that turn pigment into presence.

Emotion without Anecdote

Despite the painting’s structural rigor, it carries a mood. The model’s backward glance introduces a note of alertness and curiosity. Shadows gather around the eyes and mouth, giving the face a slight, withheld expressiveness that keeps sentiment in check. The overall atmosphere is serious rather than solemn, intimate rather than confessional. Emotion arises from form—in the dignity of the stance, the quiet authority of line, and the soft collision of warm and cool.

The Viewer’s Role

Matisse positions the viewer as a participant in constructing the image. Because detail is minimized, the eye must complete forms where contour thins or where planes meet. Because space is shallow, the viewer cannot retreat into a distant vista and is compelled to negotiate the figure’s edges at close range. This collaboration is part of the modern claim of the painting: meaning is not merely delivered; it is built between image and beholder through acts of reading.

Legacy and Continuing Relevance

Nude Study remains compelling because it reconciles opposites that continue to define modern painting: restraint and intensity, flatness and volume, immediacy and deliberation. It demonstrates how a radical reduction of means can result in a powerful sense of life. For artists, the canvas offers a lesson in building form with limited color and decisive contour. For viewers, it offers a renewed way to see the body—not as a catalog of parts but as an economy of planes that hold together like architecture. The painting is a node in Matisse’s progression, yet it stands on its own as a complete and resonant statement about the nude in the modern age.

Conclusion

Henri Matisse’s Nude Study distills the figure to its structural essentials and finds in that distillation a new kind of beauty. A handful of hues, a handful of bounding lines, and a surface alive with brushwork combine to present a body that is less described than constructed. The surrounding fields of teal and ocher give the figure breathable air; the black contour gives it weight; the drapery provides a cool foil that sharpens warmth. Painted in 1907, the work shows an artist stepping from Fauvist blaze into architectonic clarity, trusting that the human figure—composed with economy and respect—can carry modern painting’s most serious ambitions.