Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

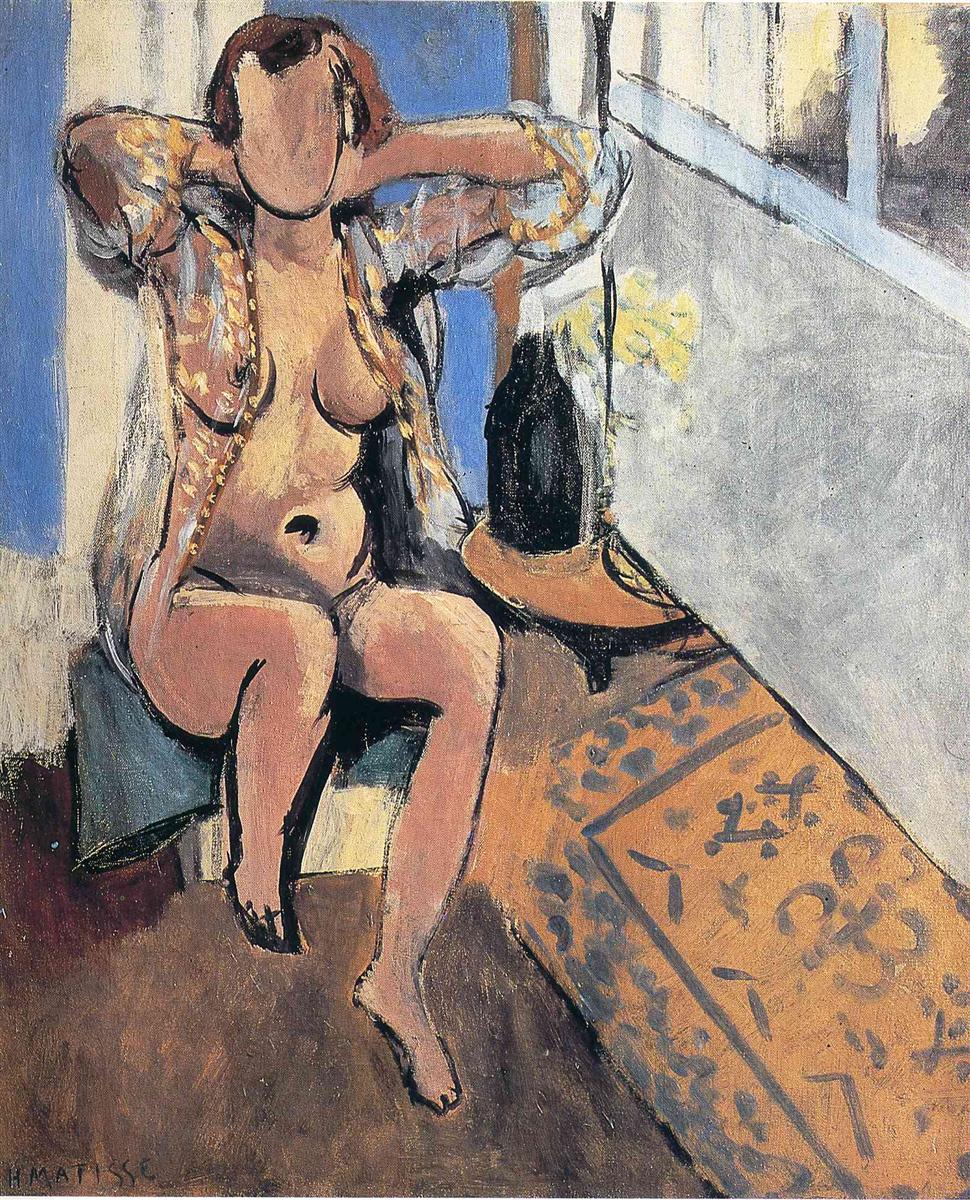

Henri Matisse’s “Nude, Spanish Carpet” (1919) takes a familiar Nice-period interior—a sunlit room with a window, textile, and chair—and charges it with the immediacy of a body at rest between movements. A seated nude occupies the lower left, legs angled toward the viewer, arms raised behind the head in a gesture that is half stretch, half arrangement of hair. A patterned robe slips from her shoulders. To the right, a diagonal wedge of ochre carpet inscribed with simplified Spanish motifs surges across the floor toward a bright plane of window light. A black bottle-shaped silhouette on a small stand and a circular hat-like disk punctuate the middle ground. The face is left broadly open, an oval with minimal definition, so that contour, posture, and color do most of the expressive work. Everything is close to the picture plane, painted with quick, stating strokes that favor decision over finish. The result is an image that feels both candid and composed—a modern nude living within an architecture of textiles and light.

The 1919 Setting: Nice, Recovery, and the Language of Interiors

Matisse painted this canvas in 1919, the first full year after World War I, while working in Nice. The artist’s Nice period is often described as a turn to serenity, but it is more accurately a reorganization. He shifted his attention from prewar extremes to measured harmonies built from rooms, windows, patterned fabrics, and models placed in shallow space. In these interiors, decoration becomes structure; pattern and color hold the composition as firmly as walls and floors. “Nude, Spanish Carpet” belongs to this program while retaining a raw, exploratory energy. Its palette is warm and deliberate, its drawing elastic, and its space compressed—signs of a painter searching for clarity through essentials rather than elaboration.

First Impressions and Motif

At first glance the eye recognizes three dominant fields: the figure’s warm rose and umber flesh; the Spanish carpet, a sloped plane of ochre inscribed with gray-blue motifs; and the cool light of the window, a big pale wedge that tilts across the right side of the canvas. Between these anchors sit a few concentrated shapes: a tall, black bottle form topped by a disk that reads as a hat, and a patch of blue sky glimpsed at the far left. The nude’s lifted arms make a wide bracket around the upper left quadrant, and the robe, striped and floral in pale tones, bridges skin and background. The face’s blankness frees the viewer from portraiture and redirects attention to relational design—angle against curve, warm against cool, textile against body.

Composition as a System of Diagonals and Planes

The composition is built on decisive diagonals. The Spanish carpet enters from the lower right corner and rides upward toward the middle, its edge echoing the tilt of the window’s bright plane above. These two slanted slabs—carpet and window—form a V that cradles the figure. Against their thrust, the vertical of the bottle silhouette and the curve of the nude’s torso stabilize the center. Cropping is close: the model’s right foot approaches the frame, the head touches the top edge, the carpet runs out of view. This nearness compresses space into a shallow stage, as if the viewer were standing at the room’s threshold. Overlap—arm before torso, robe over shoulder, bottle against hat disc—adds just enough depth to keep the stage habitable.

Color Architecture and Temperature

Color does the heavy structural work. The flesh is tuned with warm ochres, salmon pinks, and brunette shadows tinged with violet, creating the sense of sun-warmed skin. The carpet is a keyed-down saffron enlivened by gray-lilac glyphs—the “Spanish” motifs simplified into calligraphy. The window’s light, far from white, is a thin, cool mixture banded by powder blue; it acts like an illuminated wall more than a view, consistent with Matisse’s Nice interiors. The robe takes secondary hues—pale yellows, cool grays, occasional blues—and mediates between skin and background. The bottle is nearly black, yet it leans blue, keeping it in the same temperature family as the window and preventing it from becoming a dead hole. Because each color family appears in more than one zone, the harmony is tight: the blues of window, bottle, and robe converse; the ochres of skin and carpet echo across the composition; the dark calligraphy of carpet motifs rhymes with the living contour around the figure.

Light and Atmosphere

Mediterranean light enters from the right and floods the room with a steady, maritime brightness. Matisse refuses theatrical shadows; he turns forms with temperature shifts and scant value contrasts. The window’s pale plane is brushed thinly so the canvas breathes through it, giving the light a grain rather than a glare. Flesh receives warmer notes on the torso and cooler notes in the hollows of thigh and abdomen. The robe holds onto mid-tones, suggesting its gauzy fabric without literal description. This even climate keeps the painting’s mood humane and its color statements legible.

The Spanish Carpet as Structural Engine

The carpet is more than décor. It functions as a compositional engine: a bold diagonal that animates the floor, an arena of pattern that counterbalances the large plain of the window, and a warm field that amplifies the skin’s temperature. Matisse simplifies the Spanish motifs—numbers of curling shapes, dots, and letterlike signs—into a rhythmic grid that reads quickly. That rhythm is crucial. It prevents the floor from becoming a vacant plane and gives the eye a lateral movement that answers the vertical pull of the figure. The carpet’s edge is crisply drawn but not rigid; it wavers slightly, acknowledging the warp of fabric and the angle of view. In many Nice-period interiors a red lattice floor plays this role. Here the carpet is the portable architecture that turns a corner of the room into a designed stage.

The Figure: Gesture, Agency, and Modernity

The nude is neither classical nor coy. Her raised arms create breadth; her set legs anchor her weight on the chair; her torso turns slightly toward the light. The pose suggests agency: a person adjusting hair or robe rather than being arranged by an unseen hand. The blankness of the face, far from erasing identity, universalizes the action and keeps the focus on the structural dialogue between body and room. The robe slipping from her shoulders introduces interval—skin against textile, curve against fold—and pulls the body into the painting’s decorative language. Matisse has long been frank about the body’s volumes; here he states them with generous planes and living edges, refusing sentimental softening while keeping the mood calm.

Drawing and the Living Contour

Contour is everywhere and always alive. The dark line around the thigh thickens where weight gathers and thins where light spreads; the arm’s outer edge tightens at the elbow and opens across the upper arm; the curve along the abdomen is a single, confident sweep. These contours are not cages; color pushes against them and sometimes slips over, as if line and plane were negotiating. Inside the figure, drawing happens with the brush: a single, darker stroke marks the navel; quick inflections define knee and ankle; the breasts are turned with minimal modeling. Around the carpet motifs and the bottle silhouette, line becomes calligraphy, binding object to pattern.

Brushwork and Material Presence

The paint handling is varied and frank. The window plane is scumbled thin so the weave of the canvas asserts itself; the carpet is thicker, with strokes that follow the direction of the warp; the figure is painted in soft, loaded passes that blend wet into wet along transitional edges. The bottle silhouette is dense and matte, absorbing light; the hatlike disk catches a small highlight and turns with a single brush glide. In several places underlayers peek through—dark grounds around the chair, warm undertones near the knee—keeping the surface lively and reminding us that this is a record of decisions, not a polished veneer.

Space: Shallow, Breathable, Designed

Depth is created with as little means as necessary. Overlap and scale suffice: the nude sits in front of the chair; the carpet slips under her foot; the stand and bottle touch the window plane; the window brackets a band of exterior blue. No deep vista opens. This compressed space is the hallmark of the Nice interiors and a key to their modernity. It keeps the picture an object—color arranged on canvas—while still letting viewers imagine themselves in the room. The body is not a distant spectacle; it shares our air.

The Black Bottle and the Hat-Like Disk

At the model’s right sits a dark, bottle-shaped silhouette with a disk that reads as a straw hat or tray. This compact still life acts like a punctuation mark. It anchors the center, converses with the window’s cool blue, and brings a note of domestic reality into the field of pattern and skin. The bottle’s verticality cuts across the carpet’s diagonal, while the disk’s circle echoes the blankness of the face—a formal rhyme that unifies upper and middle registers. Such objects are common in Matisse’s Nice rooms: modest, functional, and structurally essential.

Rhythm and the Viewer’s Path

The eye moves in a choreographed loop. It begins at the lifted arms, slides down the torso to the crossed thighs, touches the bare foot near the carpet edge, then follows the carpet’s diagonal toward the bottle and disk. From there it climbs the stand into the window’s pale plane, drifts across the cool blue, and returns via the robe’s patterned sleeve to the figure’s shoulder. Each lap reveals a new relation: the echo of carpet motifs in the robe’s light pattern, the way the blue of the window enters the shadows of the skin, the rhyme between the circular disk and the face’s oval. The painting becomes a score for looking, not a single snapshot.

Comparisons within the Nice Nudes

Consider this canvas alongside “Reclining Nude on a Pink Couch,” “Nude on a Sofa,” or “Naked Leaning,” all from 1919. Where those paintings envelop the figure in pale whites or coral upholstery, “Nude, Spanish Carpet” sets her against a firm ochre field and an emphatic wedge of window light. The palette is less rosy and more earthbound, the drawing more visibly abbreviated, the face more openly unresolved. Yet they share core commitments: shallow space, the equality of body and pattern, and the reliance on temperature to turn form. This piece feels like the most candid of the group, a near-contemporaneous note taken in full voice.

Pattern, Ornament, and the Ethics of Clarity

Matisse’s lifelong fascination with textiles and ornament—from Islamic tiles to Moroccan rugs—surfaces here as disciplined structure. The Spanish carpet’s motifs are simplified to a legible rhythm; the robe’s pattern is kept pale so it doesn’t crowd the figure; the window’s large plane is allowed to breathe. Ornament clarifies rather than clutters. That clarity has ethical weight in 1919: it proposes that order and pleasure need not be opposites, that a room can welcome the body with dignity when relations are proportioned and seen.

The “Unfinished” Face and Modern Presence

The blank face often surprises viewers. Rather than a failure of likeness, it is a modern choice. By withholding facial detail, Matisse prevents expression from narrowing interpretation. The viewer must read posture, contour, and rhythm. The person becomes present in the act of seeing: hands raised, weight set, skin warmed by light, body integrated with the room’s design. The portrait is still there—made of relations rather than features.

Material Choices and Palette

The palette implied by the surface is concentrated: lead white for the window and robe lights; earth ochres and raw siennas for carpet and flesh underlayers; alizarin and a touch of vermilion in the warmer skin notes; ultramarine and cobalt for the cools; ivory black for the line that stiffens the case’s edges and the carpet’s inscriptions. Paint is often laid in a single, decisive pass. Where corrections occur, they are left visible—an ethic of candor that keeps the painting present tense.

How to Look Today

Stand close and let the brushwork declare materials: thin light over canvas tooth; thick ochre that sits up like pile; soft blends where flesh turns. Step back until the carpet’s glyphs merge into a hum and the body reads as a set of broad planes. Track the warm–cool alternation from carpet to skin to window and back. Notice how no area hoards attention: the figure is central, yet the room’s diagonals, patterns, and objects are partners, not props. The painting rewards this oscillation between touch and architecture, part and whole.

Conclusion

“Nude, Spanish Carpet” is a lucid, unguarded statement of Matisse’s Nice-period vision: the body furnished with air, pattern made structural, color tuned to carry space, and brushwork left legible. A slanted carpet and a slanted window build the stage; a black bottle and round disk provide punctuation; a robe mediates between skin and room; a face left open keeps attention on relations. What could be anecdote becomes a complete order. In a year dedicated to rebuilding harmony, the painting offers a model of how clarity, restraint, and pleasure can inhabit the same room.