Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction to Rembrandt’s “Nude Man Seated before a Curtain” (1646)

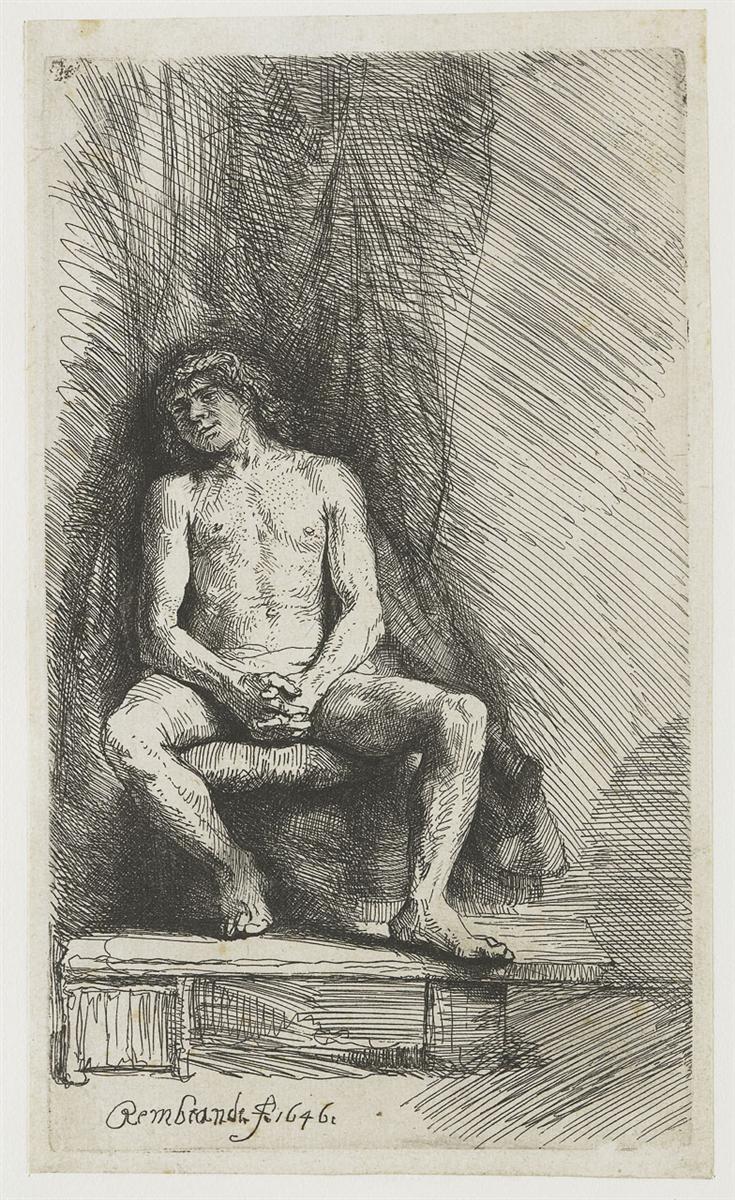

Rembrandt’s 1646 etching “Nude Man Seated before a Curtain” turns a small sheet of paper into a vast meditation on weight, breath, and thought. A young male model sits on a low block, knees apart, hands loosely clasped at the pelvis, head tipped toward the left as if listening to a distant sound. Behind him descends a heavy curtain whose cross-hatched folds create a cavern of shade. The platform beneath his feet is edged like a carpenter’s bench, its grain marked with quick strokes. Nothing in the scene distracts from the drama of posture: a body at rest that still hums with readiness. With the restrained means of etched line, Rembrandt gives the viewer access to a quiet human moment that feels immediate, honest, and complete.

A Composition Built to Hold Stillness

The design organizes space around a tightly framed triangle. The wide set of the legs forms the base; the clasped hands at the center are the hinge; the tilted head completes the apex. This triangular stability is counterweighted by diagonals in the curtain that race upward and outward, like wind in fabric. The opposition between the sitter’s still geometry and the curtain’s kinetic lines animates the sheet without disturbing its calm. The platform’s horizontals—thick, emphatic, and slightly askew—anchor the whole, keeping the figure earthbound and believable. Rembrandt places his signature along this ledge, not as a flourish but as an additional structural brace that locks the viewer’s eye in the foreground before releasing it back to the figure.

The Curtain as a Machine for Light

In place of a studio wall, Rembrandt rigs a curtain and then draws it like weather. Long, confident hatchings change direction as they cross the sheet, describing folds and weight while also manufacturing a deep tonal field. Against that man-made night the body emerges with sculptural clarity. Highlights are forged by leaving paper untouched along the clavicles, the crest of the thigh, the knee, and the bridge of the nose. Midtones arrive through delicate nets of short strokes that curve with the form. The effect recalls a marble statue suddenly discovered by lamplight, except that this “stone” breathes and sags and warms like flesh. The curtain is not a backdrop; it is a deliberate device for staging light, a portable chiaroscuro machine that lets the artist dramatize volume with line alone.

Hands, Abdomen, and the Grammar of Ease

Few details are more revealing than the hands. They interlace not in tension but in a practiced rest, knuckles loose, thumbs lightly touching. The wrists hover above the thighs instead of pressing down, suggesting a posture chosen for endurance rather than display. The abdomen above the hands is mapped with economical strokes: a shallow hollow beneath the ribs, a soft roll at the navel, a slight compression where the torso folds forward. This is not a heroic body but a working one, the anatomy of a person taking a long breath between tasks. In this grammar of ease, nothing is stiff or idealized; balance and comfort create their own beauty.

The Tilted Head and the Psychology of the Pose

The head turns and tilts, creating an oblique line through the cervical spine that contradicts the square solidity of the torso. That slant, together with the half-closed eyes and parted lips, gives the impression of listening or remembering. Rembrandt refuses theatrical expression; he lets the angle of the skull carry the psychology. Because the face is not performing for us, we read emotion through the whole orchestra of the body—shoulders that fall, a lap that opens, feet that relax. The sitter appears alone with his thoughts even though we are present, and that unselfconsciousness is what makes the moment feel true.

Weight, Contact, and the Persuasion of Small Truths

Rembrandt’s etched line records how bodies touch things. The buttocks indent the cloth on the stool; the left foot’s toes arc slightly upward as weight shifts to the heel; the right foot lies flatter, signaling asymmetry that convinces. The hands hover but seem ready to settle; the back grazes the curtain at the shoulder, flattening its folds. Each micro-truth of contact compounds into macro-persuasion. Because the pressure points are right, the viewer trusts everything else: the mass of the thighs, the relaxation of the belly, the heaviness of the eyelids.

From Academic Study to Human Encounter

In the mid-1640s, Rembrandt made a series of male nude studies that reimagined academic practice. Instead of ideal proportions and heroic contrapposto, he favored models with irregularities and poses drawn from ordinary rest—seated, slumped, stretching, waiting. “Nude Man Seated before a Curtain” belongs to this revolution. The model is not a symbol or a mythological actor; he is a person in a room. The decision places the viewer in a different relationship to the figure. We learn from him rather than admire a type. Anatomy here is not a system; it is a lived structure negotiated by breath and gravity.

The Platform as Stage and Workbench

The stepped plinth beneath the sitter reads both as stage and as furniture from a working studio. Its edges are squared briskly; its front face is cross-hatched like rough wood. This double identity mirrors the role of the pose itself—part performance, part practical rest. The model sits like an actor between scenes, but the setting reminds us that this is a workplace, a laboratory of light where the hand and eye conduct experiments. Rembrandt’s signature along the edge confirms the bench’s starring role; the print is a record of craftsmanship as much as of contemplation.

Chiaroscuro Without Paint

One of the sheet’s marvels is how Rembrandt conjures the effects of paint—glaze, impasto, soft transitions—using nothing but etched lines. Over the chest, small, slightly curved strokes lie parallel to the ribs, imitating the way light skims the surface. In the hollow of the abdomen, cross-hatching tightens and then loosens to suggest gradual shadow. The curtain’s hatchings become dense in the upper right, thinning as they arc behind the head to create a halo of breathable air. The viewer feels the scene’s climate, as if the curtain muffles sound and concentrates warmth around the sitter.

The Ethics of Looking at the Nude

Because the model is unidealized and unposed for display, the viewer’s gaze shifts from acquisitive to attentive. The wide set legs and relaxed hands might be provocative in another artist’s treatment; here they read as the mechanics of balance. The modesty comes not from concealment but from purposefulness. Rembrandt treats the body as a person’s instrument—capable, vulnerable, dignified—and he expects the same respect from the viewer. That ethic makes the print feel contemporary. In an image-saturated culture, it offers a way to look at bodies without turning them into trophies.

The Head’s Shadow and the Echo of Sculpture

The deep pool of darkness just behind the head functions like the niche behind a classical bust, throwing the profile forward. It also locates the head in space. You feel how far the hair sits from the curtain, how the skull’s volume interrupts the fall of fabric. The shadow’s contour rhymes with the hair’s rugged outline, a sculptor’s trick executed with a draftsman’s tool. The result is an illusion of three dimensions achieved without tonal wash—pure line convincing you that air circulates behind the sitter.

Rest as a Form of Readiness

Though every element argues for rest, nothing in the pose is slack. The calves retain tension, the forearms roll outward as if prepared to push, and the neck, though bent, does not collapse. Rembrandt often captures this paradox—bodies at ease that can instantly gather into action. It is the physiognomy of thoughtfulness. The pose suggests someone who has stopped to listen, not someone who has given up. This readiness is the etching’s latent energy, the quiet hum beneath its stillness.

The Viewer’s Position and the Sense of Presence

We are placed just below the platform, close enough to see the slight creases at the hip and the soft shadow beneath the jaw. The angle lets the model feel larger than the sheet, as if the platform could slide toward us. Proximity builds presence; we share the room’s air. Yet because the head turns away, our nearness does not become intrusion. Rembrandt manages a delicate balance: intimate access paired with the sitter’s inwardness. The effect is humane and confident, a trust extended to the viewer to look well.

A Dialogue with Other 1646 Figure Etchings

This print converses with Rembrandt’s “Nude Man Seated on the Ground with One Leg Extended” and the double study “A Young Man Seated and Standing,” both from the same year. In each, he simplifies setting to a minimum, lets line do the work of light, and locates psychology in posture rather than in expressive faces. “Nude Man Seated before a Curtain” is the most theatrical of the group because of the drapery’s scenic sweep, but it shares the same refusal of idealization. Together the sheets show an artist determined to make the studio a place of truth, not formula.

Technique, Plate Tone, and the Breath of Paper

Impressions of this etching vary in plate tone—the thin film of ink left on the plate at printing. When a veil of tone remains over the curtain, the background deepens into velvet shadow and the body appears to glow. Cleanly wiped impressions push the body’s drawing to the front and emphasize the crisp, graphic music of the hatchings. Either way, the paper’s slight texture reads as air, and the ink’s raised line catches light at the right angle, giving the sheet a subtle tactility that painting cannot match. The medium itself becomes part of the experience of flesh, weight, and fabric.

The Quiet Radicalism of Particularity

The sitter’s body is particular—narrow shoulders relative to hips, a slightly bulging abdomen, long, sinewy forearms, ankles that turn out. In the seventeenth century, such specificity was radical for studies of the nude, which typically advertised abstract ideals. Rembrandt’s decision to record the model as he is carries an ethical charge that resonates today: people, not types, deserve attention. The print’s beauty arises from faithful noticing rather than from the imposition of a scheme.

The Platform’s Edge and the Signature’s Role

Rembrandt nests his name and the date into the platform’s lip as if carved there. The inscription is not simply identification; it is a design element that keeps the foreground from emptiness and supplies a note of human presence—the artist in the room, acknowledging the time of the encounter. The script’s rhythm echoes the parallel lines along the ledge; it is an elegant solution to a compositional problem and a reminder that looking is a collaboration between maker, model, and later viewer.

Why the Image Still Feels New

The sheet’s freshness comes from how it honors ordinary facts: fabric falls, skin creases, breath slows, muscles rest while staying alert. There is no narrative to date, no costume to age, no emblem to decode. Its subject is a timeless human interval. Because Rembrandt lets line carry weight and light with such economy, the drawing keeps its charge across centuries. It can live on a study wall as a lesson in anatomy, on a living-room wall as a meditation on rest, or in a museum as evidence that the highest art can be made from a model, a curtain, and care.

Conclusion: A Human Pause Etched in Light

“Nude Man Seated before a Curtain” is a portrait of a pause. A young man sits with hands interlaced, head tilted, feet grounded, wrapped not in myth but in fabric and air. Behind him a curtain murmurs with lines that both shelter and stage him. Rembrandt’s etching needle translates the small physics of balance and the larger psychology of attention into marks that feel inevitable. The result is a sheet that teaches the viewer to look with patience and without agenda. In its modest scale and radical honesty, it remains one of the most eloquent statements of what a body means when it is allowed simply to be.