Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

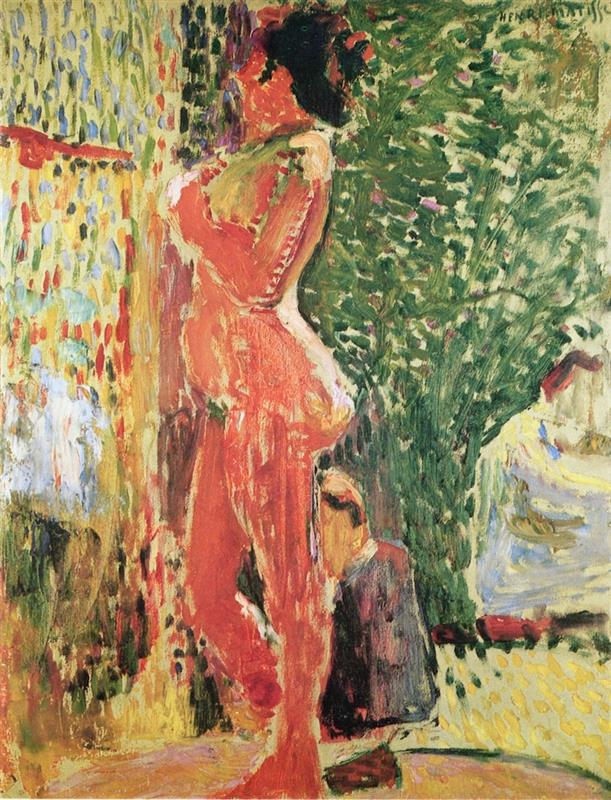

“Nude in the Studio” collapses the distance between figure and setting so thoroughly that the model seems carved out of the same weather as the room. Nothing is described with academic outlines. Instead, Matisse constructs the body—and the air around it—through juxtapositions of hot and cool color, directional strokes, and rhythms that echo across surfaces. The studio becomes a living organism of pigments: coral flesh meeting green foliage, citrine lights falling across a stippled floor, and patterned zones acting as both background and energy field. In this small yet ambitious canvas, the twenty-something painter tests ideas—chromatic structure, decorative flatness, and brush-led drawing—that will detonate a few years later in his Fauvist work.

Historical Context

The year 1899 sits at a hinge in Matisse’s development. He had digested the classical curriculum, copied old masters, and painted somber still lifes, but he was also absorbing the luminous lessons of the Midi, the constructive color of Cézanne, the domestic decor of the Nabis, and the pulse of Divisionist touch. He would never submit to a single doctrine. Instead, he synthesized: keep darks chromatic, let whites and yellows stay alive with neighboring tints, build form using temperature rather than outline, and allow brushwork itself to perform substance. “Nude in the Studio” applies this grammar to the most charged of motifs—the human body—while treating the studio not as neutral container but as a partner in visual music.

Subject and Setting

A young woman stands in profile, turned toward a patterned wall that reads like a beaded curtain or a tapestry of dabs. Her body is rendered in crescents of coral, cadmium, and rose; the hair is a dark, clipped mass, and subtle greens nibble the edges of her torso where cooler light meets warm flesh. To her right, a dense thicket of vertical greens—part plant, part painted screen—absorbs and reflects color back onto the figure. Below, a lemon-tinted floor is broken into quick lozenges, each daub a tiny reflector. A sketch-like, seated figure hovers behind the model, ghostly but present, anchoring the scene as a working studio rather than a mythic bower. The motif is modern not because of props but because of the honesty with which paint itself supplies everything: structure, climate, and intimacy.

Composition and Armature

The composition organizes itself around an emphatic vertical: the nude’s columnar stance almost touches top and bottom edges, giving the body architectural authority. She stands slightly left of center, counterbalancing the heavy greenery at right. The patterned wall creates a vertical field of prismatic dabs that echo the body’s height but in a cooler, more staccato key. The floor tilts forward in a shallow trapezoid, its diagonal checks steering the eye under the figure and into the room. A barely indicated doorway or light source seems to open at left, explaining the warmer temperatures that wash across the torso. This spare armature—one commanding vertical and two flanking fields—allows color to do maximal expressive work without sacrificing clarity.

Color Architecture

Color is the engine. Flesh is not beige; it is a chord of hot red-oranges cooled by lilac half-tones and flickers of viridian at the edge. The left background is a rain of citron, teal, and wine-colored dabs that read as textile or curtain, while the right background masses cool greens and blue-greens, like foliage brought indoors. Between them the figure glows as the warm center of a complementary triad. The floor gathers yellows, ochres, and pale violets, turning shadow into color rather than gray. Because these hues are laid in neighboring strokes, the eye mixes them optically, and the body’s roundness arises from temperature shifts rather than tonal smudging. The result is palpably modern: color both names and builds the world.

Light and Atmosphere

Illumination is broad and ambient, but it behaves as temperature rather than spotlight. Warm light swells across the clavicle, belly, and thigh, where strokes of coral and pink thicken into impasto. Cooler influences arrive from the right-hand greens, casting a faint mint along ribs and shoulder blade, which helps the torso turn without resorting to brown shadows. The floor’s lemon dabs brighten the lower half of the painting, pushing the figure forward and preventing the composition from toppling under the weight of the upper patterns. Air itself is chromatic: nothing recedes into dull neutrality, so the entire studio participates in the sensation of light.

Brushwork and Surface

Matisse assigns a distinct handwriting to each zone. The figure’s flesh is made from long, rounded pulls that follow anatomy—down the spine, across the hip, around the breast—tightening where form turns and relaxing on flatter planes. The left backdrop uses shorter, vertical dashes, like falling confetti, which activates the surface while keeping it planar. The green mass at right is knotted with curved and crisscross strokes, more vegetal in feeling, that push against the figure’s silhouette. On the floor, small lozenges of paint lie like tesserae in a mosaic. Ridges stand proud along the figure’s outline and on the brightest edges; those ridges catch real light, giving the painting a physical shimmer that echoes the optical vibration.

Drawing by Abutment

There is scarcely a drawn line. The waist appears where coral meets mint-green at a tuned value; the forearm arrives where warm flesh abuts the cooler patterned wall; the back’s contour is a seam between orange and the darker green field. The model’s profile resolves with the slightest change in temperature, not with ink-like contour. This drawing-by-abutment keeps the entire image operating under one climate of light and allows Matisse to nudge form forward or backward simply by warming or cooling an edge. The method also rescues the nude from academic rigidity. She belongs to the studio’s color-weather rather than sitting on top of it.

Space and Depth Without Rulers

The room is shallow but convincing. The floor tilts up and carries the figure’s weight; the patterned wall reads as near because its high-contrast dabs march to the edge; the green field pushes slightly back due to cooler temperatures and lower contrast; the seated figure behind the model bridges those depths as an intermediate tone. Overlaps do the rest: the nude eclipses the background; the floor’s checks disappear under her feet; the right-hand greens lace in front of and behind her contour. The space feels domestic and workable, the kind of small studio where painter, model, and props are close enough to converse.

Pattern and Decoration as Structure

A key insight of this canvas is that pattern need not be ornament; it can be structure. The dotted curtain at left provides a vertical counter-rhythm that keeps the figure from becoming a monolith. The green field at right, while vegetal, behaves like a woven texture flattened to the plane, offering resistance to the figure’s warmth. These decorative systems are not pasted on; they are integrally painted, sharing pigment families with the body and floor. Matisse learned from the Nabis that domestic pattern could carry emotion and space. Here he weds that lesson to Cézanne’s color-construction so the decorative becomes load-bearing.

The Figure as Color Engine

The nude is the canvas’s color engine. Warm to its core, it converts the room’s cooler energies into radiance. Where the body nears the lemon floor, its lower legs pick up yellow tints; where the ribs face the plant-like greens, a fringe of cooler strokes appears; where the chest turns toward the left field, pinks and creams bloom. The body doesn’t simply sit in the studio; it metabolizes the studio’s light. This reciprocity explains why the figure feels alive even without detailed modeling of hands or facial features.

Gesture, Pose, and Psychology

Her pose—one arm lifted, torso extended, head turned—combines vertical poise with a slight, sensuous twist. The ascent of red strokes along spine and shoulder suggests breath. Though the face is loosely handled, the posture reads as attentive, perhaps responding to a painter’s instruction off-canvas or to the cool surface of the wall. The seated, shadowy person behind introduces a note of everyday work: a dresser, a fellow student, or the artist in a mirror? The painting’s psychology is not theatrical but intimate. We sense concentration, warmth of skin against cool room, and the faint unease of standing under sustained scrutiny—tempered by Matisse’s affection for color’s ability to dignify the moment.

Materiality and Process

The paint’s physicality tells us about Matisse’s process. Raking strokes show him working wet-in-wet, sliding one color into another so edges breathe. Quick, discrete dabs on the curtain suggest he returned with a smaller brush to restate the pattern after major masses were set. Occasional scrapes reveal a warm ground that peeks through, knitting the palette and preventing cool areas from chilling. Such variety isn’t gratuitous texture—it is the record of decisions: thicken for light, thin for air, drag for movement, prick for sparkling surface.

Dialogues with Influences

Cézanne’s lesson is everywhere: forms turn through adjacent planes of color rather than blended shadow. From the Nabis—Bonnard, Vuillard—comes the embrace of interiors as fields of pattern, where walls and textiles serve as emotional actors. Divisionism contributes the belief that broken strokes can energize a surface, though Matisse refuses mechanical dots; his marks flex with anatomy and fabric. A kinship with Gauguin’s decorative flatness appears in the assertive verticals, yet Matisse keeps a gentler equilibrium, favoring balance over symbolism. The synthesis is unmistakably his: a humanist body held by joyful, disciplined color.

How to Look Slowly

Begin at the model’s feet, where lemon checks lap against coral toes; feel how those small temperatures root her to the floor. Climb the shin and read the alternation of warm and cool along the calf as a turning in space. At the hip, watch orange strokes bunch and curve, then thin across the belly and ribcage. Pause at the lifted arm and shoulder, where the thickest paint catches enough actual light to create a halo. Slide left into the dotted curtain, letting your eye register the vertical cadence before stepping back to the profile—notice how the face emerges from two or three temperature changes. Cross to the right-hand greens, following their crisscross until they soften into bluish light near the seated figure. Finally, take in the whole: a column of warmth poised between two fields of cool pattern, breathing the same studio air.

The Nude and Modernity

Many late-nineteenth-century nudes retreat to myth. Matisse keeps his in the studio, where paint, props, and practice make the scene modern. The work acknowledges the labor of art-making: a body holding still, a painter deciding color by color how to translate sensation, a room whose textures refuse to behave as mere backdrop. This frankness is the painting’s ethics. It insists that beauty can be built from the ordinary materials of work and attention—no allegory required.

Foreshadowing Fauvism

What will erupt in 1905 is already present: the autonomy of color, the refusal of black outline, the belief that a handful of commanding shapes can support daring harmonies, and the readiness to turn pattern into space. Intensify the palette another octave—push coral to cadmium, greens to viridian, lemons to pure light—and the canvas would still hold because its scaffold is exact. The Fauves’ seeming spontaneity rests on structural rehearsals like this one.

Relationship Between Figure and Ground

Perhaps the painting’s subtlest achievement is the equality it grants to figure and ground. The model does not dominate by sheer mass; she converses with her environment. The curtain’s dabs rhyme with the flesh’s smaller strokes; the green field’s directionality echoes the line of spine and lifted arm; the floor’s mosaic anticipates the little glints of highlight on shoulder and thigh. This reciprocity guards the image from sentimentality while protecting the dignity of the figure, who is not an isolated spectacle but a participant in a chorus of marks.

Legacy and Place in the Oeuvre

“Nude in the Studio” prefigures Matisse’s lifelong fascination with interiors where figures, fabrics, plants, and windows perform together: the Nice period odalisques, the patterned rooms of the 1910s, and even the late cut-outs’ orchestration of color against color. The canvas proves, early on, that he could apply his color-structural method to the most challenging genre—figure painting—without sacrificing either psychology or design. It stands as a compact manifesto for how twentieth-century painting might reconcile the sensual and the decorative, the human and the abstract.

Conclusion

In “Nude in the Studio” Matisse makes a proposition: let color be both description and event. A coral body rises like a flame between cool fields; pattern bears structural weight; edges are negotiated seams rather than hard lines; atmosphere is built from temperature, not wash. The studio is not a neutral box; it is climate, rhythm, resistance, and support. The nude is not a passive object; she is the engine that metabolizes the room’s light. Out of these relations Matisse builds a painting that feels at once intimate and momentous, domestic and epochal. Within a few square feet of canvas he anticipates the chromatic freedom that will soon change modern art—and he does so with nothing more than a model, a room, and the courage to let color think.