Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

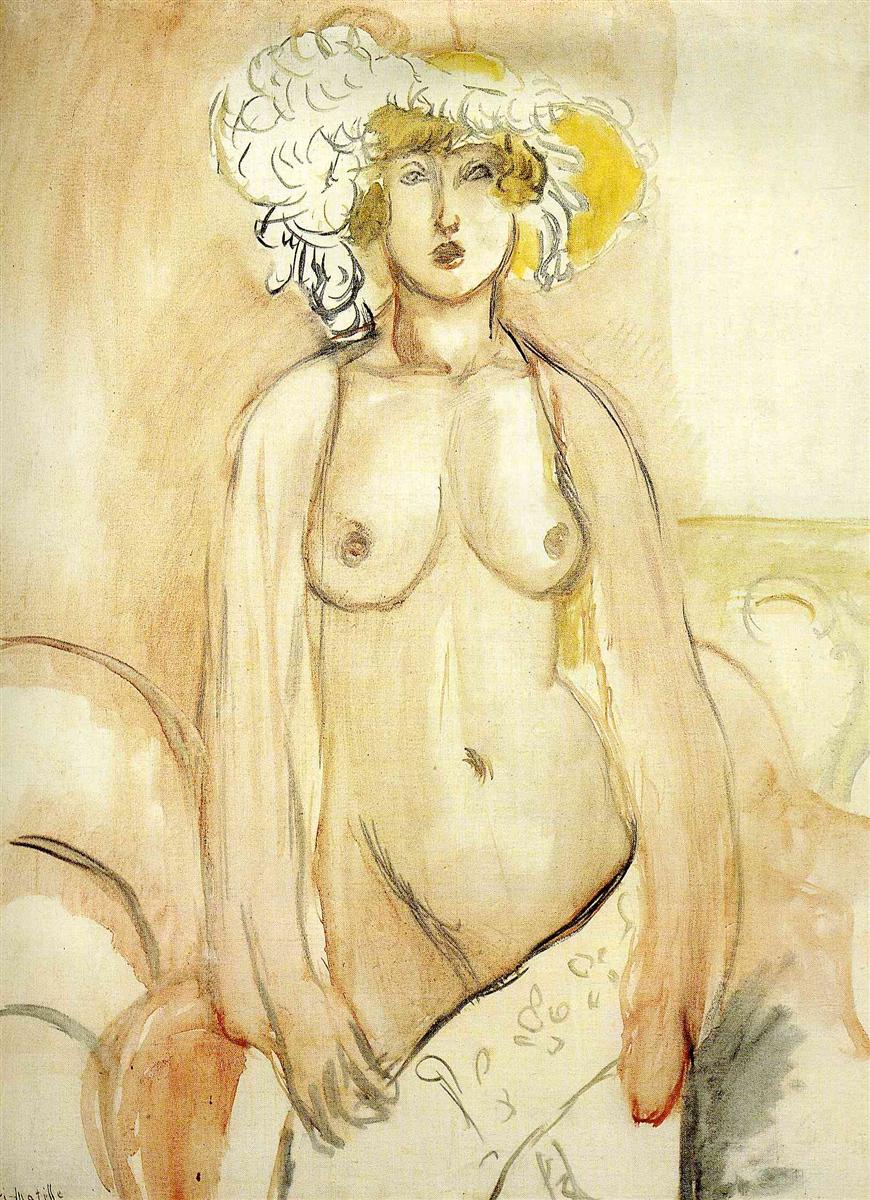

Henri Matisse’s “Nude” (1919) stages the timeless subject of the human body with a radical lightness of means. The figure stands frontal and near life-size, wearing an extravagant, feathery hat that floats above her head like a small cloud tinged with citron. Everything else is stripped to essentials. The background is a pale, breathable field; the body is modeled with transparent washes; the drawing is an elastic contour that thickens and thins to record touch and tempo. The painting reads like a revelation rather than an explanation: a nude appearing out of air.

Matisse in Nice and the Ethic of Clarity

Painted during the first years of Matisse’s so-called Nice period, this canvas belongs to a body of work that sought calm after a decade of stylistic upheaval and the trauma of war. In Nice he turned from congested experimentation toward a lucid, sunlit language grounded in measured color, open space, and domestic motifs. “Nude” exhibits the period’s essential traits—moderate palette, clear drawing, and breathable light—while taking them to an extreme of economy. Instead of building an interior with shutters, mirrors, or carpets, Matisse suspends the figure in an atmosphere so reduced that the body and the act of painting become the entire event.

First Impressions and Pose

The model stands with weight distributed evenly, arms relaxing downward, hands grazing the thighs. The head tilts slightly, eyes directed at the viewer, the mouth closed but not tense. The feathery hat, a theatrical accessory better suited to promenades than to studios, is the sole flourish. Its whiteness and halo of yellow modulate the face’s warmth and make the upper register of the picture hum. The pose avoids drama. There is no coy twisting, no mythological pretext, no narrative prop—a modern nude whose presence is achieved by composure and clarity.

Composition as Architecture of Breath

Compositionally, the figure occupies the central vertical like a classical column. Matisse frames her with two curved masses that hint at an armchair or upholstered form, but he refuses to insist on furniture. Those arcs repeat, like echoes, in the trace of hips, breasts, elbows, and the crown of the hat. The negative space is almost a partner in the portrait: expanses of pale ground flank the body and pass behind the head, giving the figure an aura of quiet. Cropping at the knees and forearms tightens the focus and pushes the viewer into a face-to-face proximity that is intimate without becoming invasive.

Palette and Color Relations

The palette is deliberately spare: warm ochres for flesh, slight rose for warmth at cheek and nipple, a cool gray-green for shadow, charcoal black for accents, and the luminous whites and lemons of the hat. Because there are so few colors, each relation carries weight. The soft yellow in the hat reappears as a subdued warmth along collarbone and belly, binding top to torso. Pale gray shadows repeat around the eye sockets and under the breasts, turning form with a nearly sculptural restraint. The background is not neutral but leans toward honey, making the figure feel bathed rather than spotlighted. Harmony comes from recurrence, not from variety.

Drawing and the Living Contour

More than any single color, line shapes this picture. Matisse’s contour has the spring and give of a reed pen, although here it is a brush charged with thin paint. Where the shoulder turns into arm, the line thickens; where it crosses the breast or shoulder blade it thins to let air through. Rather than imprison the form, the contour seems to breathe with it. Cross-contours and small interior accents—around navel, clavicle, the outer thigh—are placed with a calligrapher’s economy. This is drawing as decisive choreography, each stroke the residue of a movement that could not be improved by addition.

Water-Like Oil and the Transparency of Process

The paint film is conspicuously thin in many passages, almost watercolor laid on primed canvas. The weave is legible; the ground participates in the final tone. Matisse’s scumbles and washes allow warm under-layers to glow through cool veils, creating a sensation of light arising within the body rather than falling upon it. Where he desires emphasis—the rims of the breasts, the curve of the abdomen, the profile of the cheek—he strengthens the mixture, but still refuses opacity that would weigh the image down. The result is a nude that feels newly seen each time you look, because the making remains visible.

The Hat as Counterpoint

The flamboyant hat may at first seem incongruous on a nude, yet it performs crucial formal work. Chromatically, it contributes the painting’s highest whites and clearest yellows, raising the key of the entire canvas. Structurally, its broad oval balances the volume of torso and hips below, preventing the composition from reading as a heavy pyramid. Psychologically, it lends the figure a touch of worldly individuality—no mythic Venus, but a modern woman capable of play and style. The feathery edges echo the quick, feathery brushstrokes elsewhere, making adornment and facture rhyme.

Light Without Theatrics

Matisse restrains dramatic highlights. There is no single lamp, no bright window casting a wedge of light. Instead, an even, Mediterranean clarity permeates the space. The belly turns by temperature rather than by glare; the breasts, modeled with light gray-green and warm ochre, feel rounded without glossy accents. The hat’s whites are the nearest to brilliance and thus become the painting’s beacon. Because the ground holds to a mid-light value, the figure separates gently from it, preserving serenity. Light is not a stage effect but a pervasive climate.

Space, Furniture, and the Refusal of Clutter

Hints of upholstery and a faintly patterned drape appear at the lower edges, yet Matisse declines to articulate furniture or wallpaper. This refusal is principled. By keeping decor at the edge of recognition, he prevents anecdote from interfering with the body’s presence. The nude becomes the room’s architecture. Even the suggestion of a floral motif in the lower right is absorbed into the broader rhythm of curves and arabesques; detail is allowed only where it amplifies cadence.

Gesture and Psychology

The figure’s expression is laconic. Eyes and mouth are reduced to a few sure marks, leaving the viewer to complete feeling. The arms hang in a calm vertical, fingers slightly open, neither tense nor posed. This calmness is not indifference. It is a modern kind of poise in which dignity stems from placement rather than emotive performance. The hat reads as mischief; the direct stance reads as candor. The psychology of the painting arises from the harmony of its parts—hat to head, head to torso, torso to empty air—more than from any melodrama of face.

Comparison with Matisse’s Other Nudes of 1919

Across 1919 Matisse painted several nudes reclining on couches or set within richly patterned interiors. Those works—the pink couch, the Spanish carpet, the sofa scenes—explore plush fabrics and framed spaces. The present “Nude” is comparatively ascetic. Its economy makes it closer to a drawing in paint, an experiment in how little is required to conjure the human body in luminous air. Where the interiors rely on the dialogue between figure and setting, this canvas trusts the body and the arabesque of the contour to carry the picture. It is a distilled statement within the Nice cycle.

A Likely Palette and Studio Practice

The harmony suggests a concise selection of pigments. Lead white and a warm priming ground provide the light reserve. Yellow ochre and raw sienna establish flesh warmth; a touch of red lake or vermilion warms cheeks and nipples; ultramarine and a whisper of viridian cool the shadow notes. Ivory black, perhaps mixed into ultramarine for soft grays, gives firmness to the eyes, hairline, and a few structural edges. Thinners and medium are used liberally to achieve the watercolor-like washes. The sequence of work seems to run from a swift drawing in paint, to broad washes for flesh, to reinforcing accents along the contour and in the face and hat.

Rhythm and the Eye’s Path

The painting invites a circulating gaze. Many viewers begin at the bright plume of the hat, descend the delicate slope of forehead to the concise eyes and mouth, continue down the sternum to the navel, and then sweep outward along the arc of hip and thigh. The eye then returns upward via the soft drape or the opposite arm, meeting again the buoyant oval of the hat. Each circuit rehearses the picture’s chief rhymes: feathery hat to feathery brushwork; warm ochre of torso to warm ground; pale gray of shadow to pale gray of background washes. This rhythm replaces narrative with the sensation of continual arrival.

Meaning Without Allegory

What does this “Nude” intend beyond its evident beauty? It argues that the modern nude need not be mythic, eroticized to spectacle, or wrapped in anecdote. The body, approached with repose and precision, can be a site where paint reveals the world’s steadiness. The hat, an accessory of urban fashion, plants the sitter in contemporary life even as the rest of the image touches the timeless. Matisse offers an ethics of attention: minimum means, maximum clarity, dignity achieved by relation rather than costume.

How to Look, Practically

Approach the painting close enough to feel the canvas weave breathe through the washes. Notice how shadows at the ribs and hip are nothing more than a slight cool shift, and yet volume arrives. Track the contour with your eyes—how it swells at elbow and wrist, thins at breast edge, opens at the arm where the background seems to pour through. Step back and let the hat’s whiteness recalibrate the entire key; feel how it keeps the upper half buoyant. Attend to the absence of hard edges; the figure is moored by relations rather than by outlines alone. The longer you look, the more the picture behaves like a slow inhalation.

Reception and Legacy

While the Nice interiors often steal attention with their patterned richness, works like this “Nude” illuminate why Matisse remained central to twentieth-century painting: he could subtract almost everything and still keep sensation full. Later artists—from the School of Paris to postwar painters of the figure—learned from this union of decisiveness and restraint. The canvas stands as a reminder that clarity is not simplicity’s opposite but its reward.

Conclusion

“Nude” is Matisse at his most distilled. With a few colors, a living contour, and washes thin enough to let the ground breathe, he makes a human body stand before us as if newly seen. The hat’s buoyant plume keeps the composition aloft; the body’s measured warmth anchors it; the pale field holds both in equilibrium. Freed from allegory and anecdote, the painting offers an experience of presence that feels at once intimate and spacious, fragile and assured. It is a modern classic precisely because it is so unforced: the nude as a clear note held in sunlit air.