Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

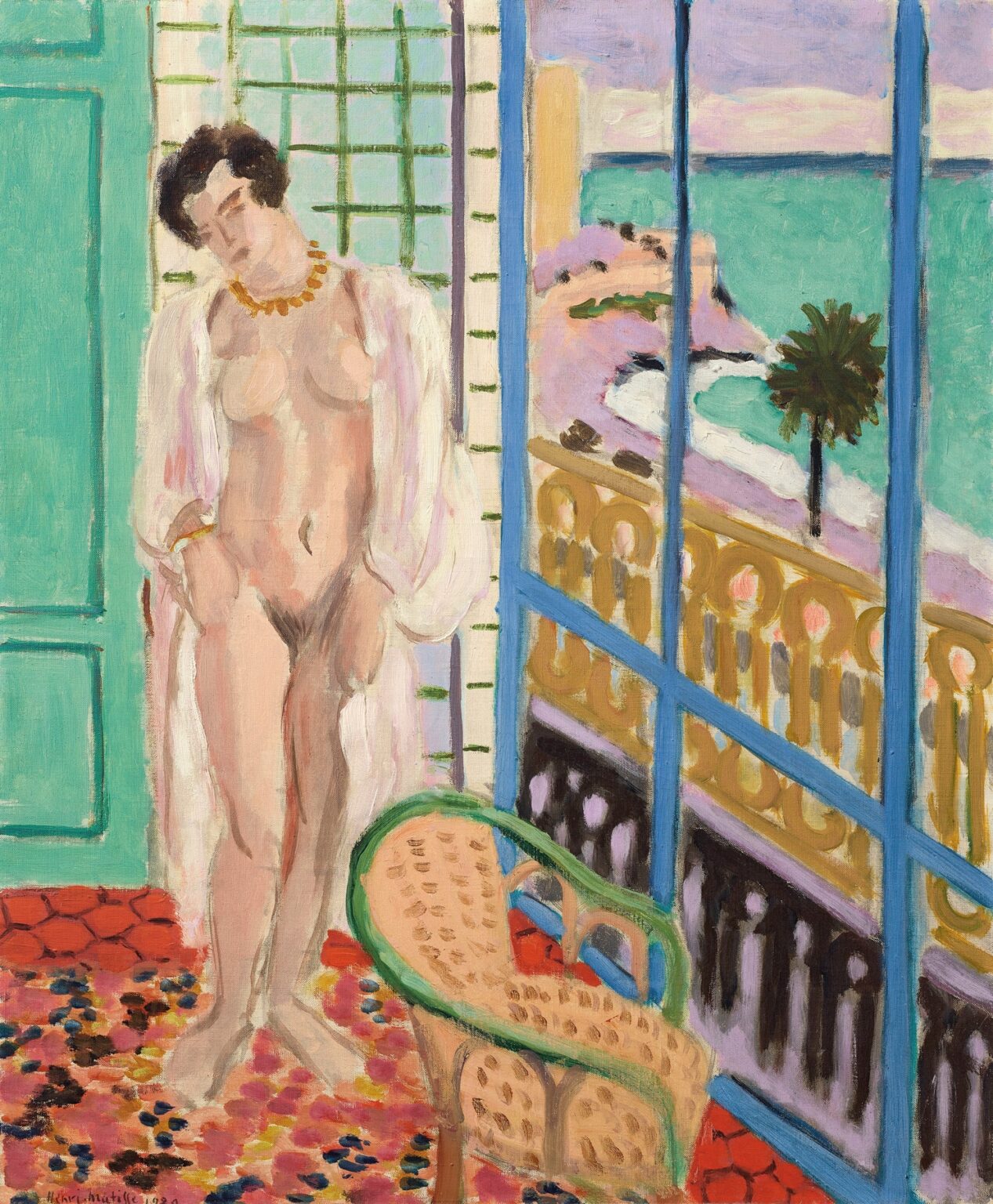

Henri Matisse’s “Nude at the Window” (1929) is a luminous drama of interior and exterior, a modern odalisque caught where room and seascape meet. A standing model, nude but for a loose robe that slips from her shoulders, occupies the left half of the canvas. She leans slightly, head bowed with a dreamy tilt, a necklace and bracelet catching the room’s warm light. On the right, a tall window opens to a balcony and a sweep of turquoise sea, pink promenade, and a solitary palm. The room glows with patterned red floor tiles, mint-green woodwork, and a cane chair edged in green, while a gridded wall and blue window mullions erect a quiet architecture behind the figure. The painting belongs to Matisse’s Nice years, when he became the supreme choreographer of color, light, and décor, and it shows the artist at ease with a grammar he had refined for over a decade: black contour as architecture, pure color as climate, pattern as pulse.

The Nice Years And The Theatre Of The Window

Matisse’s long residency on the French Riviera was more than an address; it was a pictorial laboratory. Hotel rooms and rented apartments with tiled floors, shutters, patterned screens, and sea views furnished him with endlessly recombinable parts. In this period he repeatedly staged the interplay between near and far by placing a model at a threshold—a balcony or open casement—so that the Mediterranean’s clear light presses into the decorated intimacy of the room. “Nude at the Window” is an archetypal statement of that strategy. The figure is not secluded; she is bathed by air that seems to flow through the blue mullions and gold balcony. The window is both a literal opening and a structural device that lets Matisse counterpose interior pattern with exterior breadth.

Composition As A Dialogue Of Planes

The composition divides into large, legible zones. To the left, the nude stands against a wall articulated by a green grid and a mint door; below her feet spreads a rose-red floor beaded with darker and lighter blossoms of paint. The center is occupied by a cane chair that turns on a diagonal, its oval back echoing the curve of the model’s hip. The right half of the painting is a tall screen of blue verticals and diagonals framing the balcony and sea. These planes are not deep in the academic sense; Matisse compresses space into a shallow stage. Yet the meeting of planes—the wall and the window, the floor and the balcony—sets up a convincing geography. The viewer feels the weight of the room and the breath of the outdoors at once.

The Nude As Axis

Matisse builds the figure with his characteristic economy. A supple black contour sets the profile of cheek and brow; soft, warm planes model breast, belly, and thigh; small, darker accents lightly indicate nipples, navel, and the shadow of the arm. The head inclines with a lyrical fatigue, and the arms fall in relaxed asymmetry, one hand disappearing into the robe’s folds. The necklace, a string of warm ochre beads, gathers the light and ties the flesh to the surrounding palette. The body is at once ornamental and individual: simplified enough to belong to the room’s decorative logic, yet present enough to confer human temperature. By standing instead of reclining, the model becomes an axis against which the room turns, a column of flesh that answers the window’s blue uprights.

Color As Climate And Direction

The painting’s palette is a climate rather than a census of local tones. Mint green across the door and chair rim cools the left side of the canvas, while the floor’s hot reds and crimsons provide ground heat. The sea beyond the balcony is a saturated turquoise flecked with creamy breakers and lavender sky; those cools reach back into the room through the blue of the mullions and the pale mauves in the robe. Gold—most insistently in the balcony grill—warms and stabilizes the right edge, echoing in the model’s jewelry. Because values are mostly mid-tones, temperature does the spatial work: warm hues advance, cool hues recede, and the eye moves easily from chamber to coast.

Pattern, Ornament, And The Pulse Of The Room

Pattern in the Nice interiors is never filler; it is the pulse of the painting. Here, the tiled floor’s red field dappled with irregular petals acts like a low drum. The gridded wall behind the figure supplies a counter-rhythm of measured vertical and horizontal touches, the kind of motif Matisse gleaned from North African screens and shutters. The balcony’s balustrade adds another pattern layer—golden, looping, almost musical—that bridges décor and architecture. By staging three kinds of repetition—floor blossoms, wall grid, balcony arabesque—Matisse composes a polyrhythmic environment in which the nude can rest without vanishing.

The Window As Instrument

Few artists treat windows with such structural intelligence. Matisse’s blue mullions are not just frames for a view; they are actors that hold the right side in place and carry color from sea to room. The diagonals of the casement tilt, energizing the verticals and implying an open, swung window even without literal hinges. The balcony’s golden railing behaves like a warm threshold, so that the cool sea does not simply punch a hole in the wall but flows through a band of light. The window becomes a tool for orchestrating temperature, rhythm, and directional energy across the canvas.

The Cane Chair As Echo And Counterpoint

At the painting’s center sits a cane chair edged in green. Its oval back echoes the curving hips of the model, and its diagonal placement counters the vertical insistence of the mullions. The pale cane lattice within the chair quietly rhymes with the wall’s grid, a reprise that helps the eye cross from figure to window. Matisse uses chairs throughout the Nice years as mediators—furniture that belongs to décor but can converse with bodies and architecture alike. Here the chair’s green rim is especially useful: it catches the door’s mint, bridges to the sea’s turquoise, and grounds the figure’s warmer flesh.

Drawing With The Brush

Although color dominates, the painting is built on decisive drawing with the brush. The black contour around the figure is elastic, thickening at the outline of the arm, thinning at the jaw, and sharpening at the knee. The chair and balcony carry similar outlines, so line unites disparate materials—skin, rattan, metal—into one language. Interior modeling is kept to a minimum: a handful of gray-brown strokes in the face, a gentle shadow along the thigh, a wash inside the robe. Matisse trusts contour and placement to deliver volume, which keeps the painting light and breathing.

Light That Is Painted, Not Illustrated

Mediterranean light is the subject as much as the nude or the sea. Matisse paints it as a condition of color rather than a diagram of highlights and shadows. The flesh is suffused with warm pinks and creams; the robe is pushed into pale lilacs and whites that read as light rather than fabric; the balcony rails gleam simply by their relationship to surrounding blues and lavenders. There is almost no cast shadow. Instead, zones of temperature describe the way sun presses against room and body. The effect is clarity without glare, warmth without heaviness.

The Poise Between Privacy And Publicness

“Nude at the Window” stages a delicate hinge between the privacy of the studio and the public expanse beyond. The figure’s tilted head and inward posture suggest reverie, a moment of interior life. Yet the open window, the glittering rail, and the visible promenade introduce the hum of the world. Rather than drama, Matisse prefers poise: the body does not pose for the street; it simply exists at the edge of a view. This equilibrium—self-contained figure, outward-facing room—gives the painting its gentle tension.

Ornament And The Modern Nude

Matisse modernizes the odalisque by shifting emphasis from exotic anecdote to decorative order. The jewelry and robe nod to the genre’s lineage, but the model is not staged as a fantasy figure; she is a presence among color-structures. The nude is here because flesh is the best partner for the room’s climate: it receives light, answers the red floor, and makes the window’s cools meaningful. Ornament is the grammar that allows the modern nude to breathe without narrative burdens.

Space Without Illusionism

Depth in the painting comes from overlap and temperature, not from a painstaking perspective scheme. The chair overlaps the balcony, the figure overlaps the wall, the mullions overlap the view. Warm reds and golds push forward, cool sea tones sink back. The floor tilts gently, not because of vanishing orthogonals but because of the scale of its motifs and the tone of the red. This simplified space is fuller than any architectural rendering; it feels lived-in, navigable, and sufficient for the painting’s aims.

The Role Of Small Accents

Matisse’s mastery often hides in small decisions. The ochre necklace and bracelet repeat the balcony’s gold and keep warmth near the face and hand. The dark palm tree outside supplies a single vertical accent that punctuates the turquoise and runs counter to the window’s blue lines. The white surf and lavender shadows on the coast introduce a pastel glow that slips into the robe; they are transitions, not details. Such accents allow the eye to travel around the canvas in satisfying circuits.

Material Candor And The Pleasure Of Paint

The painting’s surfaces remain frank and lively. The floor’s red is laid in with confident, mottled touches; the wall’s grid is a quick green flick; the sea is a flat yet vibrating field modulated by soft bands. You see the weave of the canvas through thin passages, and thicker brushstrokes on the balcony catch light. This candor suits Matisse’s ethics of clarity: rather than seduce with polish, he invites the viewer into the making.

Kinships And Differences Within The Nice Series

Placed among companions from the late 1920s, “Nude at the Window” shares family traits—shallow space, patterned tile, cane furniture, north–south blues and greens, a threshold view—but it also distinguishes itself by the dominance of the standing figure and the openness of the window. Some Nice interiors pull curtains or screens across the vista, corralling the exterior into pure pattern. Here the view is legible as coastline and palm, which shifts the mood from salon to balcony and makes the room feel closer to sea air.

Rhythm Of Looking

Matisse designs a path for the eye. We begin at the face because the head leans against a pale wall; we follow the necklace to the torso, then down the robe to the glowing floor. From there, the diagonal of the cane chair sends us right into the blue mullions, out across the gold rail to the turquoise sea and palm. The arc returns up the mullions and back across the gridded wall to the model’s tilted head. The painting is built to be toured in this loop, a gentle choreography as steady as tide.

The Human Tone

Despite the room’s strong design, the painting’s enduring note is humane. The model’s stance is unforced; the tilt of the head and softness of the belly are tender rather than idealized. The ornaments are modest; the robe is simply a veil of tone. Matisse’s art here is not a spectacle of virtuosity but a hospitality of seeing: the viewer is invited into a space where color and body coexist without anxiety.

Lessons In Design

“Nude at the Window” crystallizes several lessons that continue to guide painters and designers. Color can carry structure when values are controlled and edges are clear. Pattern becomes rhythm when it is varied and placed in dialogue with other patterns. Windows and borders can perform architecture, not just enclose it. Figures can be simplified to the point where they join décor without losing their presence. And small accents—jewelry, a single tree, a diagonal chair—can clinch the whole.

Conclusion

Henri Matisse turns a simple situation—a nude standing by an open window—into a complete world of relations. The mint door, gridded wall, red floor, cane chair, and blue mullions are not props; they are notes in a chord through which Mediterranean air vibrates. The balcony’s gold glows like a cadenza; the sea’s turquoise opens the throat of the room; the figure’s warm body delivers the human key. “Nude at the Window” sustains the Nice period’s promise: clarity without coldness, ornament without excess, intimacy within luminous space. It is a painting to live in and to breathe with.