Image source: wikiart.org

Historical Moment And Why This Picture Matters

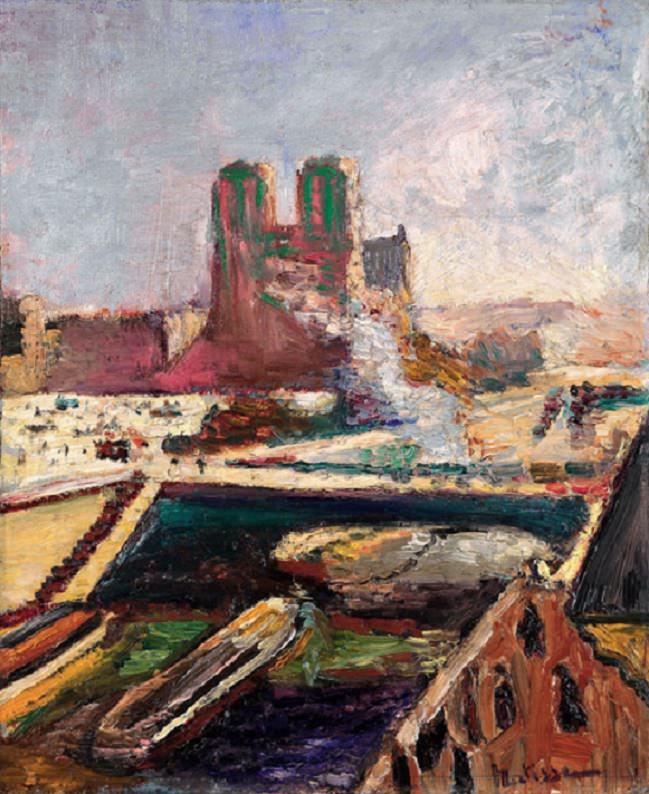

“Notre Dame” from 1900 sits at a hinge point in Henri Matisse’s development, when he was moving away from academic finish and the tonal naturalism he learned at the École des Beaux-Arts toward a bolder, more autonomous use of color and paint. Paris at the turn of the century was still the stage for debates launched by Impressionism and Post-Impressionism: how to translate modern sensation, how to treat color as a constructive power rather than a veil over drawing, how to compress time and feeling into a single, charged surface. Matisse’s canvas participates in all of these questions by taking one of the city’s most stable icons—the cathedral of Notre-Dame—and making it newly unstable, pulsing, and contemporaneous.

The View From The Left Bank

In 1899 Matisse took a studio on the quai Saint-Michel, just across the Seine from the cathedral. Many of his early twentieth-century views look from that window or its immediate environs, and this painting carries the feeling of a vantage point pressed close to glass. The near edge of the scene is crowded by a sharply angled roofline in the lower right, as if a dormer or attic ridge intrudes into our peripheral vision. The bridge and the slate ribbon of river squeeze horizontally through the middle distance, and beyond them the twin towers rise in a ruddy block. The structure is familiar, but the framing is personal: the city is not a postcard view but a lived panorama stitched together from glances, oblique diagonals, and the memory of dawns and afternoons spent watching the light pivot around the island.

Composition As A System Of Pressures

The picture is organized by crossing forces rather than by classical perspective. A wide, dark band of water spans the lower third, pinning the composition horizontally. Against it, three diagonals counterpunch: the bright ocher path at left that slides inward, the long planklike form and greenery that thrust from the bottom center, and the steep roof at right. These trajectories converge toward the cathedral, which holds the center not only as a landmark but as a fulcrum for all the surrounding motion. The upper zone, light and vaporous, expands like a bell of atmosphere, while the lower zone is compressed, built from dense slabs of pigment. The result is a city that breathes: inhaling at the horizon, exhaling in the foreground.

Color As Architecture

Although the subject is a stone building, the architecture that truly erects this painting is color. The cathedral’s mass is pitched in rasping reds and bruised violets, with unexpected slashes of viridian in the towers. These greens are not descriptive; they are structural accents that pull the verticals forward and set them vibrating against the pinks. Across the river the water turns into a band of saturated blue-green, neither wholly shadow nor reflection but a chromatic counterweight to the warm monument beyond. Sand and cream tones stretch across the quays; burnished oranges and wine-dark browns anchor the immediate foreground. Nothing is local color in the academic sense. Instead, each hue is chosen to achieve relationships: warm against cool, high-chroma against dulled mixtures, matte against glossier smears. The cathedral holds together not because Matisse has modeled every buttress but because the colors lock like masonry.

The Brush As Weather

The paint handling is thick, brief, and impatient with smooth illusion. Short strokes knit the sky into a field of active light, the brush moving in small eddies that echo the turbulence of clouds and the low glare of a pale sun. On the ground and water, the marks lengthen and flatten, laying down streaks that suggest current and roadway without enumerating bricks or ripples. In the central plume of brightness—perhaps smoke, perhaps light ricocheting along the Île de la Cité—strokes collide and tangle. The effect is meteorological. Paris is not simply depicted; it is weathered into being. That physicality matters historically because it anticipates the confidence of later Matisse, for whom paint would increasingly stand in for the world rather than imitate it.

Light And Time Of Day

The palette and the relative lack of cast shadows suggest late morning or a thin afternoon when the sky washes the architecture rather than carving it. The light is nonhierarchical; it refuses to spotlight a single hero and instead saturates the entire surface. A soft bloom at the right edge dilates into a halo that catches on the cathedral’s shoulders and dissolves detail toward the periphery. This is a painterly solution to a modern problem: cities change by the minute, and no one vantage can fully grasp them. By letting light fray forms and by distributing illumination, Matisse allows time to register as a generalized, continuous sensation.

Abbreviation And The Courage To Omit

Even in 1900 Matisse is already practicing a discipline of omission that would become central to his mature style. The cathedral’s rose window is not plotted, the sculpted portals are implied by a darker base, and the individual stones are nowhere to be seen. Boats, pedestrians, carriages collapse into chips of tone. What remains is what is necessary to read the scene: the vertical pairing of towers, the broad sill of the river, the right-angled geometry of Parisian roofs. Omission here is not carelessness but a strategy to keep the viewer’s eye mobile, to make the brain complete the scene and thus participate in its animation.

Notre-Dame As A Modern Motif

Painters repeatedly return to cathedrals not only for their forms but for what they signify: the persistence of the past inside the present. In this picture Notre-Dame is less an emblem of medieval endurance than a barometer of a city in flux. It is colored by modern pigments and surrounded by modern circulation systems. The bridge becomes a conveyor, the river a dark, moving belt. Setting the venerable monument inside an energetic, chromatic economy turns the motif into a statement about continuity and change. The sacred architecture is neither revered at a distance nor ironized; it is absorbed into daily experience, which is a deeply modern posture.

Relationship To Impressionism And Post-Impressionism

Matisse borrows the Impressionist interest in optical freshness but pushes beyond it. The palette is cleaner and more extreme than Monet’s early Notre-Dame series, and the forms are chunkier, closer to Cézanne’s constructive planes. The paint drags with an almost sculptural density that resists mere sparkle. One can sense Matisse studying Cézanne’s lessons about using color to build volume while also flirting with the high-keyed intensity that would erupt in Fauvism a few years later. In that sense the painting functions as a small primer for the twentieth century’s central discoveries: color as structure, the surface as an autonomous reality, and the edited sign as a replacement for exhaustive description.

The Birth Of Expressive Distortion

Look closely at the towers. Their edges are softened and slightly splayed, as if the mass were exhaling. Strict perspective has given way to the perspective of feeling. Vertical and horizontal lines are kept as cues, but they serve rhythm more than measurement. The green accents along the towers are odd if one insists on verisimilitude, yet utterly right if one recognizes them as notes inside a chromatic chord that keeps the towers alive against the surrounding atmosphere. Distortion here is never theatrical. It is measured and musical, guiding the eye from roof to bridge to water to cathedral in a loop that replays the painter’s looking.

Surface, Scale, And The Body

The strokes are scaled to the hand and arm, not to the architectural subject. That mismatch produces a small but telling friction: a vast monument is articulated by gestures that remember the body. Viewers often experience this as intimacy. Even without knowing the exact size of the canvas, one senses a human-sized performance inscribed in the pigment, which makes the distance between painter and motif feel short. This intimacy aligns with the windowsill vantage and with the way the right-hand roof presses into the picture. The body is near the city; the city is inside the body’s reach.

Materiality And The City’s Texture

Paris around 1900 was a mosaic of surfaces: wet stone, soot, green water, plaster façades, new iron bridges. Matisse mirrors that variety through shifts in paint quality. Some passages are scumbled so that lower layers breathe through; others are laid on opaque, like cut tiles. The river’s band is smoother, as if the brush skimmed, while the foreground ridges are ridged and dragged, echoing shingles or barges. This material mimesis substitutes for literal detail, creating a tactile equivalence rather than a literal inventory of things.

Memory, Perception, And The Role Of Abstraction

Despite its recognizable subject, the painting leans toward abstraction as a mode of memory. The key elements are simplified into blocks, wedges, and bands that would still cohere even if one stripped away the name “Notre-Dame.” That remove from literalness allows the picture to function as an archetype of a city seen from above water, with a monument at center. Abstraction here is not a denial of place; it is the means by which the place can be made general, and therefore shareable. In a later decade Matisse would radicalize this approach with flatter color fields and cut-outs, but the germ is already present: to distill a scene until it becomes a formula for sensation.

The Mood Of Paris At The Turn Of The Century

There is no obvious drama in the picture—no ceremony on the parvis, no overt weather event—yet the emotional climate is restless and optimistic. The color choices produce a hum of energy, especially where the warm reds of the cathedral meet the cool greens of the river and towers. The city seems to be waking, with smoke or mist lifting, traffic beginning, water moving. The mood suits the era’s faith in progress and the artist’s own sense of forward motion. Nothing in the painting is static; even the most massive element seems ready to adjust under the pressure of light.

Comparisons With Later Notre-Dame Views By Matisse

A fruitful way to read this canvas is to place it along the arc that leads to Matisse’s later, sparer views of the same monument. In subsequent years he would reduce the cathedral to more planar silhouettes, sometimes a few lines and fields of color. By contrast, the 1900 painting is tactile and packed, but the logic is the same: find the minimum required to declare the motif and then energize the remaining forms through color relationships. The early picture demonstrates the transition. It retains the throb of observed detail while practicing ruthless selection, and it insists that a painting can remain legible while being openly constructed.

Space, Depth, And The Role Of The Horizon

Although the painting contains traditional depth cues—a river recessing, a bridge crossing, a skyline at the back—space is ultimately flattened into a sequence of stacked plates. The horizon dissolves into a pale atmospheric band rather than a crisp line, and the bridge acts like a hinge between foreground and distance. This stacking is critical, because it keeps the eye at the surface where color and texture can do their work. Matisse is not trying to open a hole into another world; he is building a fully sufficient world on the canvas plane. The sense of depth comes and goes like a mirage, depending on whether one attends to the subject or to the paint.

The Human Figure Without Figures

There are no discrete figures here, yet the suggestion of human presence is everywhere: specks that read as pedestrians on the quay, the implied movement of barges, smoke that presumes burning fuel, architecture that presumes occupation. Matisse often found ways to let the city feel peopled without narrating it. That choice keeps the painting from becoming anecdotal. Instead of telling a story about specific actors, the image tells a story about urban life as a set of flows—of light, water, commerce, and looking.

Continuities With The Decorative Ideal

Matisse would later speak about his desire to create an art of balance, purity, and serenity, akin to a good armchair for the tired businessman. While this early cityscape is more agitated than those late pronouncements suggest, one can already feel the seeds of that decorative ideal. The interlocking color zones form an ornamental pattern across the surface; the diagonals and rectangles could be read as pieces in a tapestry. The cathedral, for all its weight, contributes chiefly as a silhouette to be harmonized. In that sense the painting is an early rehearsal for Matisse’s lifelong negotiation between representation and decoration.

What The Painting Teaches About Seeing

“Notre Dame” proposes a method of seeing the modern world that remains instructive. It asks the viewer to accept the shorthand of marks and the autonomy of color, to reconstruct the city from cues rather than from lists of facts, and to recognize that fidelity to experience sometimes requires unfaithfulness to appearances. The image functions like a conversation between eye and mind: the eye offers a sensation of red tower against green river, the mind supplies architecture and geography. In this negotiated space, painting becomes a way to train perception itself.

Legacy And Place In Matisse’s Oeuvre

This canvas does not announce a movement the way the later Fauve works would, but it clears ground for them. It demonstrates the security with which Matisse could depart from tonal observation, and it shows how urban subject matter could be transformed by color without losing identity. The Notre-Dame series, of which this is an early member, provided the artist with a stable motif against which to measure his own evolution. Returning to the same cathedral over the years, he could test each new idea about structure, color, and surface. In 1900 the test already yields a persuasive answer: the city can be rebuilt in paint, and in being rebuilt it can feel more vividly itself.