Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

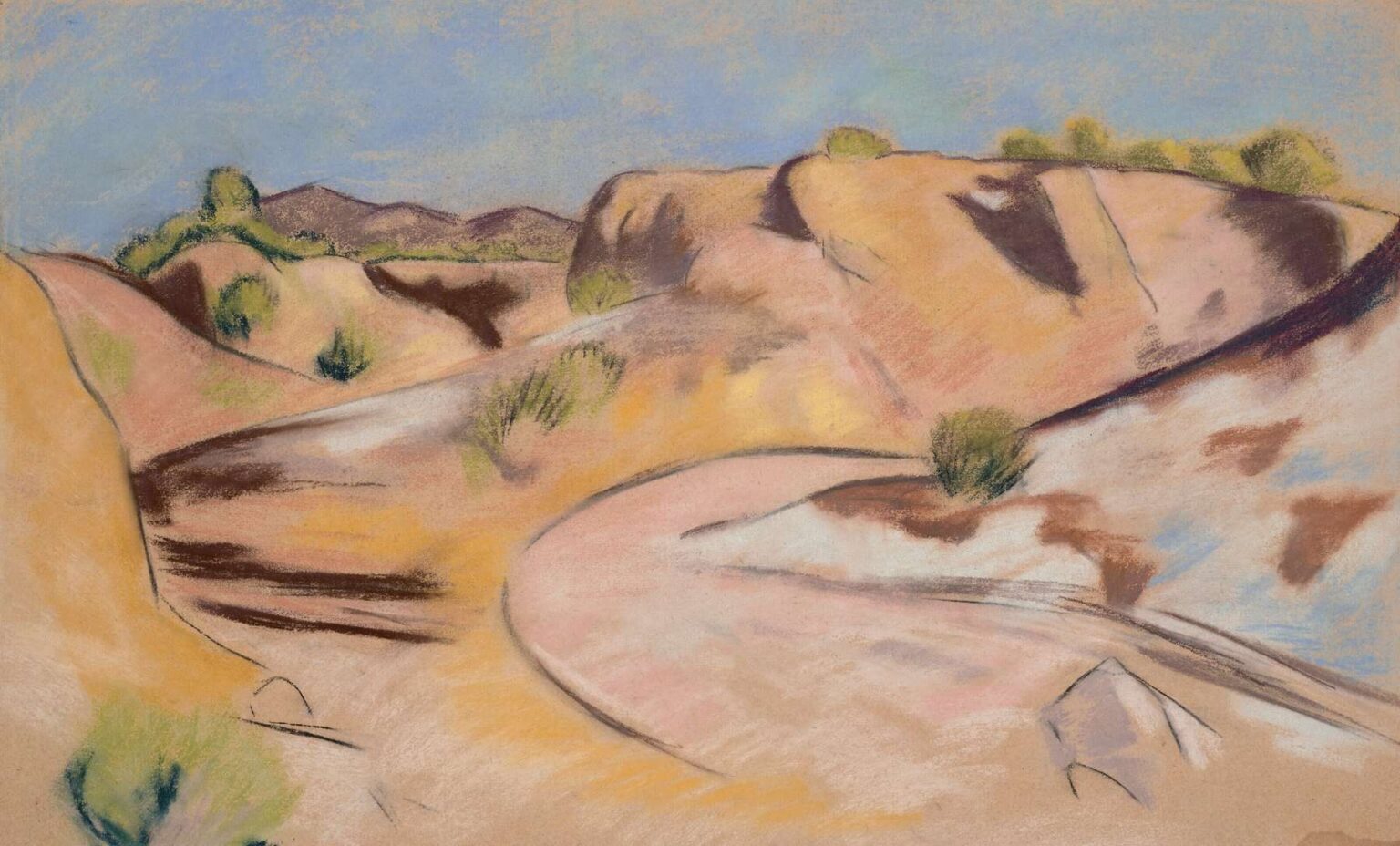

Marsden Hartley’s New Mexico (1918) captures an arid arroyo curling through sun‑blasted hills, all rendered in velvety pastel strokes that pulse with heat and quiet introspection. At first glance, the scene appears simple: ochre and rose earth forms, sparse tufts of green, a cobalt sky washed thin by desert glare. Yet the drawing condenses a pivotal moment in Hartley’s development, when the artist—fresh from European avant‑garde circles and bruised by wartime loss—turned to the American Southwest as a site for spiritual recalibration and formal experiment. In this work, he translates the land’s sinuous geology into an abstracted choreography of line, contour, and color fields, forging a uniquely American modernism that neither romanticizes nor merely documents the terrain but uses it as a crucible for inner vision.

Historical Context: Hartley in 1918 and the Lure of the Southwest

The year 1918 found Hartley in a state of profound transition. He had spent much of the preceding decade abroad, absorbing Cubism, Fauvism, and German Expressionism, and had produced searing allegorical canvases in Berlin memorializing a fallen friend. The trauma of World War I and the deaths that shadowed it left him seeking solace in new geographies. The American Southwest—New Mexico in particular—offered an antidote to European tumult: vast horizons, ancient cultures, and geological time palpable in eroded mesas and dry riverbeds. Hartley journeyed west as many modernists would, driven by curiosity and the promise of a landscape seemingly unspoiled by industrial modernity. New Mexico stands as an early fruit of this exploration, executed not in the heavy impasto of oil but in the immediacy of pastel, a choice that underscores both the spontaneity of his vision and the powder‑dry atmosphere of the desert itself.

The New Mexican Landscape as Modernist Laboratory

For Hartley, the desert was not merely a picturesque subject; it was a laboratory for distilling form. The Southwest’s stripped‑down topography—bare hills, scrub brush, dry washes—offered elemental shapes that could be readily abstracted without losing their identity. In New Mexico, the meandering arroyo becomes a sweeping ribbon that guides the eye through the composition, while the flanking bluffs mass into gently faceted planes. Hartley suppresses extraneous detail so that the drawing hovers between representation and abstraction. The scene does not insist on a precise location; instead, it becomes an archetype of desert space, a mental construct as much as a transcription from nature. This approach allowed Hartley to reconcile the spiritual intensity he sought with the formal clarity he admired in European modernism.

Medium, Technique, and the Pastel Surface

Pastel suited Hartley’s need for speed and tactility in the field. Unlike oil, which demands drying time and layers, pastel can be laid down and reworked instantly, encouraging bold, sweeping gestures. In New Mexico, the paper’s warm tone participates actively in the image, glowing through thinly applied passages and enriching the earthen palette. Hartley scumbles soft veils of peach, yellow ochre, and pale violet across large zones, then asserts form with firmer, charcoal‑dark contours. The surface retains a powdery bloom characteristic of pastel, evoking the dust that hangs in desert air. This granularity amplifies the drawing’s sensuous appeal while reminding viewers of its material presence: pigment ground to dust, akin to the very earth it depicts.

Composition and Spatial Flow Through the Arroyo

Hartley orchestrates the viewer’s journey with the arc of the dry wash, which sweeps from the lower right, curves inward, and vanishes behind a bluff. This S‑curve imparts motion to a static scene, suggesting geological forces shaped over millennia. The path also functions psychologically, implying a pilgrimage into the heart of the landscape, a metaphor for Hartley’s own inward trek after grief. The flanking hills rise like guardians, their rounded tops echoing one another and creating a rhythm of repetition that stabilizes the picture plane. A distant purple ridge anchors the horizon, compressing depth so that foreground and background converse more as layered bands than as a deep perspectival tunnel. Space thus becomes tactile and traversable, not illusory, aligning with modernist efforts to keep the viewer aware of the surface even while suggesting distance.

Color Language of Desert Light

The desert is often imagined as monochrome, but Hartley finds a spectrum: apricot sands, mauve shadows, sage‑green shrubs, periwinkle sky. He avoids saturated primaries, choosing instead a chalky, sun‑bleached range that communicates the high, desiccating light of New Mexico afternoons. Warm and cool hues interlace subtly. The arroyo’s bed shifts from pale pink to creamy white to faint blue, hinting at evaporated water and mineral deposits. Darker maroon and umber patches punctuate the slopes, registering erosional scars or pockets of deeper shade. Small flashes of emerald and chartreuse mark the scant vegetation, their intensity heightened by the surrounding neutrals. Hartley’s chromatic restraint lends the work a quiet hum rather than a shout, aligning mood with the contemplative solitude of the site.

Line, Contour, and Gesture as Structural Forces

While color carries atmosphere, line in New Mexico confers structure. Hartley’s contours are economical yet expressive: a single sweeping stroke can define the crest of a hill, while a handful of short, angular marks conjure a shrub. Where necessary, he darkens the edge, thickening it to assert a plane’s weight or the arroyo’s edge. Elsewhere, he allows lines to dissolve, letting form be inferred rather than locked down. This oscillation between decisiveness and ambiguity animates the drawing, keeping the eye alert. Gestural marks—quick hatchings, tapers, and smudges—register the artist’s hand at work, turning the landscape into a record of motion both natural and human. In doing so, Hartley reiterates a central tenet of modernism: the artwork is not a window onto reality but an event, a process visible on the surface.

Symbolic and Psychological Readings

Although Hartley rarely imposed explicit narratives on his landscapes, his choice of subjects often mirrored inner states. The dry wash suggests absence and potential simultaneously: water has been here, will come again, but is not present now. Such temporality resonates with Hartley’s grief and longing in the wake of wartime loss. The path that curves out of sight invites speculation about what lies beyond, echoing spiritual quests that never quite reveal their end. The sparse vegetation, clinging to life in harsh conditions, could be read as a symbol of resilience. Yet the drawing resists melodrama; its mood is contemplative rather than tragic. Hartley seems to find solace in the land’s endurance, its slow cycles dwarfing human turmoil. In that sense, New Mexico becomes a quiet affirmation that healing can occur in empty spaces where silence reigns.

Dialogue with European Avant‑Garde and American Regionalism

Hartley’s formal simplifications and emphasis on contour recall lessons from Cézanne, Gauguin, and the German Expressionists. The compression of space, the broad color planes, and the evident brush—or rather, pastel—stroke all reflect European modernist strategies. At the same time, his subject choice aligns him with a burgeoning American regionalism, one that sought authenticity in indigenous landscapes rather than European salons. Unlike the Social Realists who foregrounded human labor, Hartley finds the American spirit in geology and light. New Mexico thus occupies a middle ground: it is neither a didactic regionalist scene nor a purely abstract modernist construct, but a synthesis in which American place and European form merge.

Relationship to Hartley’s Broader Oeuvre

Seen against Hartley’s career arc, New Mexico illuminates continuities and shifts. Before 1918, his Berlin works used symbolic objects—flags, helmets, medals—to stand in for human figures. In New Mexico, the symbols become geological: arroyos, hills, and shrubs serve as emblems. Later, in Maine, he would monumentalize mountains and seas with similar formal economy. The pastel medium itself foreshadows Hartley’s later works on paper in the 1930s and 1940s, where he embraced immediacy and graphic clarity. Moreover, the drawing’s curving pathway anticipates the serpentine roads and rivers in his postwar landscapes. Thus, New Mexico operates as a hinge piece, connecting his European symbolist phase to his mature American landscapes through the vehicle of place.

Legacy and Contemporary Relevance

Hartley’s Southwestern works were undervalued for decades, overshadowed by his German period and late Maine iconography. Today, however, scholars and artists alike recognize their importance in forging a vernacular modernism. New Mexico resonates with contemporary painters who explore liminal spaces between abstraction and representation, and with Indigenous and Latinx artists reasserting the Southwest’s cultural narratives. The drawing’s sensitivity to land without exploitation, its refusal to exoticize, offers a model of engagement that feels ethically pertinent now. In an era of climate anxiety, Hartley’s attention to aridity, erosion, and resilient plant life also reads as prescient, reminding viewers that landscapes are dynamic, fragile systems rather than static backdrops.

Conclusion

New Mexico (1918) distills Marsden Hartley’s search for a spiritual and formal equilibrium into a single, sinuous composition. Pastel becomes dust, contour becomes canyon rim, color becomes heat haze, and the artist’s restless hand finds momentary stillness in the arc of an arroyo. By paring the scene to essentials—curve, plane, muted hue—Hartley creates a landscape that is at once specific and universal, an ode to the American Southwest and a manifesto for a modernism rooted in place. The drawing invites prolonged looking, rewarding viewers with the subtle rhythms of desert topography and the deeper pulse of an artist aligning outer sight with inner vision.