Image source: artvee.com

Historical Context: Munch in Wartime Scandinavia

In 1915 Edvard Munch was in his early fifties and Europe was engulfed in the First World War. Although Norway remained officially neutral, the conflict’s shadow stretched across the continent, unsettling artists who sought refuge in themes of nature and inner life. Munch, having experienced personal traumas in earlier decades—his mother’s death, his sister’s illness, his own mental breakdowns—responded to the collective crisis by retreating into symbolic landscapes. “Neutralia” reflects this impulse: rather than depicting battlefields, Munch turns to an Edenic motif of nude figures in a pastoral setting. The title itself—Latin for “lands of neutrality”—underscores his identification with Norway’s non-belligerent stance while hinting at psychological states of suspension, ambivalence, and longing for emotional balance. In this wartime print, Munch offers viewers both an escape from and a reflection on the anxieties of early twentieth-century Europe.

Medium and Technique: Color Woodcut as Expressive Vehicle

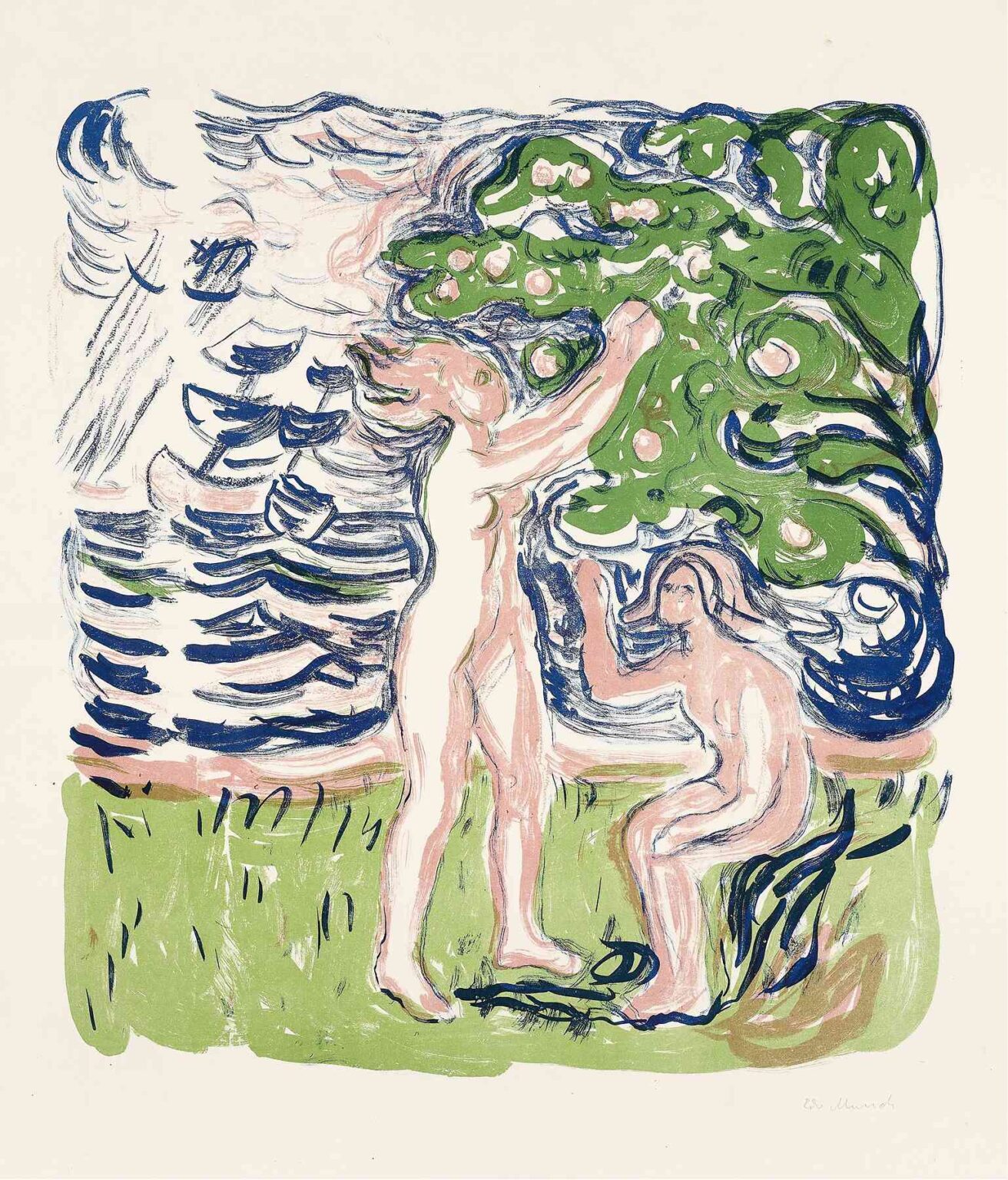

“Neutralia” is executed as a color woodcut, a medium Munch embraced around 1909 and refined through the 1910s. He carved multiple wooden blocks—each inked with a different hue—and printed them in succession on Japanese or Fabriano paper. The textured grain of the wood appears across large areas of color, lending organic variation to flat fields of green and pink. Munch then often added hand-applied touches of watercolor or tempera to enrich the palette. In “Neutralia,” swirling strokes of Prussian blue define the water’s surface, while pastel rose and lime green establish land, foliage, and flesh tones. The registers between blocks are deliberately imprecise: edges of green sometimes overlap the pink tree trunk, and the blue shoreline intrudes into the grass. These slight misalignments heighten the print’s vibrancy and underscore the hand-made quality that Munch valued as an extension of his emotional investment in each image.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics: A Harmonious Triad

Munch arranges “Neutralia” within a near-square format, dividing the scene into three horizontal zones: the grassy foreground, the tree and figures in midground, and the swirling water and sky above. The standing figure anchors the center, her upward gesture reaching for fruit in the overhead canopy. To her right, a seated companion gazes upward, creating a triangular compositional structure that guides the viewer’s eye in a gentle loop. The tree’s rounded crown echoes the figures’ curves, while the horizontal undulations of the shoreline contrast with the verticality of trunks and bodies. This interplay of vertical, horizontal, and diagonal elements yields a stable yet dynamic balance. By omitting background landmarks, Munch collapses depth, emphasizing psychological space over naturalistic perspective. The print thus becomes a stage for archetypal human interaction rather than a depiction of a specific locale.

Subject Matter and Thematic Layers: Neutrality, Nature, and Desire

On the surface, “Neutralia” shows two nude youths gathering fruit by the water’s edge—an idyllic pastime reminiscent of mythic scenes of the Garden of Eden or classical bacchanals. Yet Munch infuses the composition with layers of meaning. The title evokes Norway’s political neutrality during World War I, suggesting a national identity rooted in peaceful communion with nature. Psychologically, neutrality can also denote emotional equilibrium or detachment, a state the figures may be seeking through their ritual of gathering sustenance. Their nudity underscores vulnerability and authenticity, while the act of plucking fruit connotes desire, nourishment, and the cycle of life. The harmonious pastel palette tempers any erotic tension, framing the scene instead as a search for elemental balance amid external chaos.

Color Palette: Pastels as Emotional Tone

Munch’s use of pastel green, rose, and blue diverges from the darker, more foreboding colors of his earlier Symbolist works. The grass is a fresh celadon, the tree trunk a soft peach, and the water a pale ultramarine. Flesh tones merge with the landscape in delicate rose-beige strokes, blurring the boundary between human and nature. This restrained palette evokes springtime renewal and psychological calm. Yet subtle shifts—darker navy in the water’s wavelets, deeper emerald in the foliage’s shadows—hint at underlying tensions. The color relationships follow principles of harmony: cool greens recede, warm pinks advance, and the mid-tone blue unites sky and sea. Unlike the saturated reds of Madonna, these pastels proclaim serenity, aligning with the print’s theme of neutrality and emotional repose.

Line and Gesture: Expressive Simplicity

Munch’s line work in “Neutralia” balances calligraphic flourish with economy. The figures’ outlines are drawn in single, confident strokes that undulate gently to capture bodily curves and weight distribution. The standing figure’s raised arm is elongated to emphasize both reach and grace. The seated figure’s bent posture, rendered in softer lines, conveys contemplation. Tree branches and shoreline wavelets emerge from rhythmic, broken strokes that recall Munch’s earlier Expressionist drawings. There is minimal cross-hatching; instead, areas of shading rely on the woodcut’s negative spaces and block grain. This sparseness allows each line to carry emotional weight, transforming a simple pastoral motif into a living gesture.

Psychological Interpretation: The Search for Equilibrium

While “Neutralia” can be read as a literal pastoral scene, Munch’s deeper intention lies in its psychological resonance. The balancing act between two figures—one active, one reflective—mirrors the human tension between engagement and introspection. The act of reaching upward suggests aspiration toward ideals—peace, innocence, unity—while the seated companion embodies receptivity and inner focus. The tree, heavy with fruit yet rooted in firm soil, stands for stability and support. In wartime Europe, neutrality was both a political stance and a psychological refuge: a desire to remain centered amid upheaval. Munch externalizes this inner yearning in the print’s harmonious forms and tranquil palette.

Relation to Munch’s Evolving Style

“Neutralia” belongs to Munch’s fifteenth decade, during which his style softened from the jagged angst of his Jugendstil period to a more lyrical lyricism. Earlier works like The Dance of Life (1899) pulsate with erotic energy and stark contrasts; by 1915, Munch had embraced gentler rhythms and pastel hues, focusing on nature’s restorative power. His wartime prints—portraits, landscapes, and allegories—reveal a turn toward hope and renewal without abandoning his preoccupation with life’s fragility. Technically, his color woodcuts matured in crispness and subtle layering, enabling him to capture both spontaneity and depth. “Neutralia” thus stands at the crossroads of Munch’s evolution: it retains his symbolic intensity while offering a more meditative vision.

Provenance and Exhibition History

Shortly after its creation, impressions of “Neutralia” entered private collections in Stockholm and Kristiania, where Munch maintained close ties with Norwegian art patrons. From the 1920s onward, the print appeared in prestigious exhibitions of Munch’s woodcuts in Berlin and Paris, illustrating his mastery of the medium. In the postwar period, major museums such as the Munch Museum in Oslo and the National Gallery of Denmark acquired key impressions, ensuring its place in the canon of early 20th-century printmaking. Today, “Neutralia” is frequently included in retrospectives exploring Munch’s wartime output and his contributions to modern color print techniques.

Critical Reception and Scholarly Perspectives

Early critics praised “Neutralia” for its lyrical beauty and technical refinement, though some dismissed it as a tranquilizing departure from Munch’s earlier drama. Mid-century scholars reevaluated wartime works as integral to understanding Munch’s sustained engagement with existential themes. Feminist readings highlight the nude figures’ agency and the absence of overt eroticism, interpreting the scene as a proto-feminist communion with nature. Contemporary art historians emphasize “Neutralia” as a key example of printmaking’s expressive potential—where registration errors and woodgrain irregularities become part of the aesthetic. The print’s layered meanings continue to inspire interdisciplinary studies in psychology, political symbolism, and the art of neutrality.

Legacy and Influence on Modern Printmaking

Munch’s color woodcuts of the 1910s, including “Neutralia”, paved the way for later modernists to explore multi-block printing as a fine art. German Expressionists such as Emil Nolde and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff adopted similar techniques, using wood-grain textures and bold color planes to convey emotional states. Contemporary printmakers cite Munch’s integration of hand-applied color washes as a model for blending reproducibility with artistic spontaneity. “Neutralia” in particular is celebrated for its synthesis of political allegory and pastoral lyricism, inspiring artists who seek to address social themes through the intimate scale of prints.

Conclusion: A Poetic Vision of Peace and Vulnerability

Edvard Munch’s “Neutralia” (1915) transcends a simple pastoral idyll to become a poetic exploration of neutrality as political stance, psychological refuge, and spiritual aspiration. Through the interplay of simplified figures, harmonious pastels, and expressive woodcut lines, Munch crafts a vision of human vulnerability anchored in nature’s tranquility. The standing and seated youths enacting a ritual of gathering fruit symbolize both active aspiration and contemplative receptivity—echoing the tension between engagement and detachment that defined wartime Europe. As a technical tour de force in color woodcut and a thematic meditation on balance amid crisis, “Neutralia” occupies a unique place in Munch’s oeuvre and continues to resonate with viewers seeking solace and insight in art’s quiet power.