Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

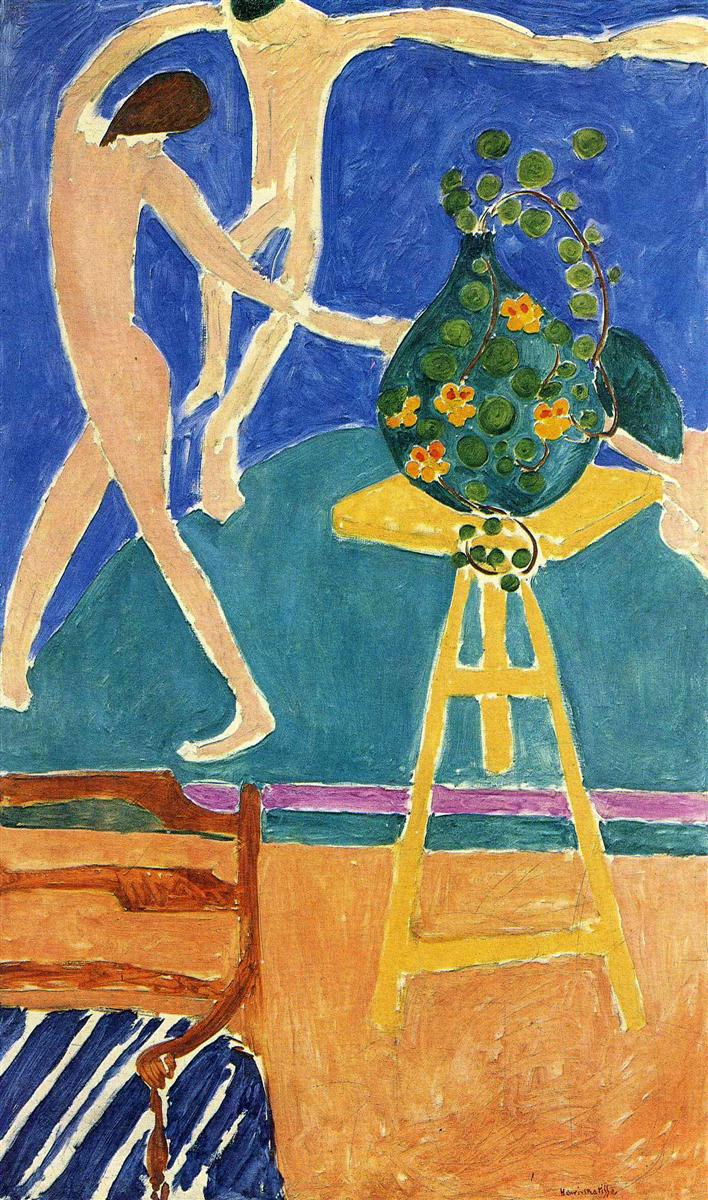

Henri Matisse’s “Nasturtiums with ‘The Dance’” (1912) is a studio picture that stages a meeting between two temperaments within the artist’s practice: the intimate still life and the monumental decorative panel. On a small yellow trestle table a plump, green vessel filled with nasturtiums tilts toward us; beside it a wooden chair anchors the foreground. Behind these domestic objects rises a vast blue field inhabited by linked, nude figures from Matisse’s earlier composition “The Dance.” The result is a painting within a painting, a dialogue between movement and stillness, and a concentrated statement of the artist’s belief that color and line can create a complete world.

Historical Moment

The year 1912 finds Matisse at a pivot. The upheaval of Fauvism had passed, but its discoveries—saturated color, flat planes, audacious simplification—remained his foundation. He had just painted interiors of fierce chromatic power and would soon travel to Morocco, where the intensity of light sharpened his sense of clear, high-key color. At the same time, Cubism was pushing Paris toward analytic fragmentation. Matisse chose a different path: instead of disassembling objects, he would fuse them through color harmonies and arabesque line, knitting the pictured space into a decorative unity. “Nasturtiums with ‘The Dance’” crystallizes that choice.

The Painting Within the Painting

The backdrop of interlaced dancers is a direct quotation of Matisse’s own “The Dance,” originally executed on a grand scale for a Russian patron. By echoing that composition on the studio wall, Matisse turns the canvas into a conversation across his own oeuvre. The dancers embody pure, ritual movement: arcing bodies join hands to make a ring that pulses like a heartbeat. They are not observers to the still life; they are its invisible energy source. The insertion of “The Dance” is not a mere souvenir but a conceptual device that lets Matisse propose that the dynamism of the human figure and the calm of a tabletop still life can belong to the same pictorial symphony.

Composition as Orchestration

The design is a rigorously controlled play of circles, diagonals, and frames. The round tabletop echoes the circular chain of dancers and the coin-like leaves of the nasturtiums, establishing a rhythm of discs that move the eye around the surface. The yellow trestle legs thrust diagonally downward, countering the lateral sweep of the dancers’ arms. A chair enters at the lower left like a low chord, giving the composition a base note. The major shapes are kept large and simple so that their relationships, not their details, carry the expressive message. Everything is flattened slightly toward the picture plane, letting the painting read as a tapestry of interlocking forms.

Color Architecture

Matisse builds the scene out of a handful of architectural colors: ultramarine blue for the wall, turquoise-green for the table platform, orange for the floor, and lemon yellow for the trestle. These are not descriptive in the naturalistic sense; they are structural tones that establish emotional climate and spatial logic. Blue and orange, complementary opposites, set up a high-voltage contrast that energizes the whole canvas. The green of the vase and table modulates between them, acting as a bridge. The nasturtiums’ small orange blossoms spark against the greens like accents in chamber music. Color becomes the grammar by which the disparate elements—human movement, pottery, furniture—are made to speak one language.

The Expressive Line

Outlines in chalky white and dark strokes mark the dancers, stool, and chair. These contours are not fences; they are currents. Matisse’s line has the quality of an arabesque: elastic, continuous, and rhythmic. It does not simply describe edges but instructs the eye how to travel through the painting. The curve from a dancer’s shoulder to wrist repeats in the vine looping from the vase neck; the hooked scroll of the chair’s arm echoes in a trailing tendril. Even where the brush leaves a raw seam of ground around a form, that gap vibrates like a drawn line. The painting thus offers two interwoven melodies—one of color fields, one of linear arabesques—that combine into a single, memorable motif.

Space Without Illusion

Perspective here is deliberately unstable. The tabletop tilts too steeply, the stool legs spread as if on a shallow stage, and the wall refuses to recede. Rather than simulating depth through vanishing points, Matisse creates a hierarchical space where the wall is a vast backdrop and the still life floats in front of it like a set piece. Overlapping does the work that perspective once did: the vase crosses the edge of the table; the table cuts into the blue field; the chair overlaps the floor and rug. This stacking of zones flattens while also clarifying relations, directing attention to the compositional logic rather than to optical realism.

Movement and Stillness

The core drama is the meeting of kinetic and static energies. The dancers are all motion—limbs flung outward, torsos bending, the implied circle never fully closed because bodies extend beyond the canvas edge. The still life, by contrast, is poised and weighty. The round leaves spread like little shields, and the squat vase anchors the composition. Yet the still life is not inert: tendrils curl, the handle arcs, and the flowers create flecks of rhythm. Matisse balances these conditions so that the quiet objects seem charged by the dancers’ pulse, while the dancers acquire substance by being tethered to the calm furniture. The painting becomes a meditation on how art can hold both serenity and vitality at once.

The Motif of the Circle

Circles knit the painting together. The dance itself is a ring. The tabletop is a circle, echoed again in the dots of leaves and blossoms. Even the negative space between two linked arms reads circularly. The roundness of forms forms a counterpoint to the rectilinear trestle and the planks of the floor. Through repetition of the circle, Matisse declares the unity of the composition: the world of the studio is not fragmented; it revolves around a single, sustaining pattern of motion.

Still Life Reimagined

Nasturtiums are a modest subject. Their disc-like leaves and bright orange flowers make them ideal for graphic simplification. In Matisse’s hands they become agents of structure. Their forms permit him to set a cadence of spots across the green mass of the vase and to rhyme with the dancers’ rounded limbs. Symbolically, the plant’s jaunty, trailing growth speaks to spontaneity and pleasure—appropriate companions to dance. The still life is thus far from merely decorative; it is the hinge that connects the domestic realm of objects to the idealized realm of communal ritual behind it.

The Studio as Theatre

Matisse often transformed his studio into a stage on which paintings, fabrics, furniture, and plants performed roles. Here the space is both literal and metaphorical. The chair suggests the artist’s daily presence; the laid rugs and colored floorboards read like set dressing. On this stage, the painting “The Dance” becomes a living backdrop. By painting his own painting into the scene, Matisse claims that art is not separate from life but circulates within it—leaning above a stool, glowing over a work table, sharing the air with flowers. The studio becomes the place where the energies of the world are rehearsed and recomposed.

Material Surface and Brushwork

Close inspection reveals the tactility of the paint. Large areas are laid in as flat, opaque passages, but the brush occasionally scumbles, leaving undercolor to breathe through. Along edges, Matisse sometimes leaves a pale halo, allowing the primed ground to register and sharpen contours. The surface is not polished to invisibility; it tells the story of its making. The density of blue differs from the comparatively thin orange of the floor; the green of the table is rubbed to varying transparencies, which causes it to shimmer between solid platform and color veil. This material variety keeps the eye alert while supporting the overall clarity.

Dialogue with Tradition and the Avant-Garde

Matisse’s tilted table recalls the modern still-life space pioneered by Paul Cézanne, who taught painters to treat the tabletop like a small landscape of shifting planes. But where Cézanne built with small tonal bricks, Matisse leaps in broad color slabs. He also engages Gauguin’s decorative flattening and interest in the expressive power of contour. In 1912, as Picasso and Braque analyzed form into facets, Matisse presents an alternative modernism grounded in color harmony and ornamental unity. The painting also converses with the decorative arts—carpets, textiles, ceramics—asserting that the boundary between “fine” and “applied” art is porous when color and rhythm are primary.

The Afterlife of “The Dance”

When he quotes “The Dance,” Matisse is not simply repeating himself. In the earlier mural the dancers float in an endless, open landscape; here they inhabit the studio, hemmed by furniture and table edge. The quotation is scaled down and cropped, becoming a motif rather than a world. This change of context lets Matisse reflect on how large public art can live inside private space. It also allows him to demonstrate that the essence of that celebrated mural—the ring of energy, the bodily sense of rhythm—can be carried by the humbler language of still life and interior.

Morocco in the Background

Although the setting is the French studio, the painting’s temperature hints at the luminous climate that would mark Matisse’s Moroccan canvases from the same year. The crystalline blues and saturated oranges feel sun-struck; forms are simplified as if seen through bright, dry air. The shift is not ethnographic but optical: the artist pursues a clarity of color intervals that approximates the sensation of bright light. In that sense, “Nasturtiums with ‘The Dance’” belongs to the broader endeavor of 1912–13, when Matisse was refining a register of colors capable of holding a scene without reliance on shadow and modeling.

Scale, Cropping, and Modern Vision

The composition is aggressively cropped. Dancers shear out of the frame; the chair is truncated; the table is cut by the canvas edge. This cropping suggests a modern, photographic way of seeing, but it also emphasizes that the painting is an autonomous surface. What matters is not the completeness of objects but the intensity of relationships at the edges where they touch and interrupt one another. The viewer is invited to feel the picture as a living fragment, a slice of a longer visual rhythm continuing offstage.

Interior Harmony as Theme

Matisse often spoke of his desire to give the viewer a sense of repose, like a good armchair. In this painting, repose is not the absence of energy but its coordination. Every element participates in a controlled harmony: the dancers’ centrifugal motion, the vase’s gravitas, the trestle’s oblique thrusts, the chair’s curving arm, the cool wall and warm floor. The harmony is achieved not by suppressing contrast but by tuning it. The blue/orange opposition is fierce, yet it is balanced by interposed greens; the dynamic dancers are offset by a sturdy still life; linear arabesque overlays broad color fields. The whole becomes a durable, breathable equilibrium.

Relationship to Other Studio Pictures

Seen alongside “The Red Studio” from the year before, this painting reveals a persistent fascination with the artist’s workroom as a microcosm. In “The Red Studio,” Matisse floods the space with a single color field. Here he keeps distinct zones, allowing the confrontation between field and object to play out more explicitly. Later interiors with goldfish and patterned fabrics will elaborate this logic by piling decorative motifs into complex tapestries. “Nasturtiums with ‘The Dance’” is a concise, almost didactic version of that project, where fewer elements make the underlying principles easy to read.

Emotional Tone

Despite the dancers’ nudity and outward motion, the painting feels domestic and humane rather than wild. The warmth of the floor and stool, the homeliness of the chair, and the friendly plant temper the grandeur of the quoted mural. Matisse does not dramatize psychological conflict; he arranges pleasures. The dancers suggest communal joy rather than frenzy; the flowers suggest cultivated beauty rather than ostentation. This emotional clarity helps explain the painting’s enduring appeal: it promises a world where intense sensations can coexist with comfort.

Why the Work Matters

“Nasturtiums with ‘The Dance’” is one of Matisse’s clearest demonstrations that modern painting could abandon traditional modeling, renounce deep perspective, and still communicate structure, emotion, and meaning with extraordinary directness. It shows an artist inventing a coherent pictorial universe using very few tools: high-key color, decisive contour, and large, legible shapes. It bridges the gap between the private realm of objects and the idealized realm of communal ritual, making a case for art’s ability to suffuse everyday life. The painting also speaks to self-reflection in modern art: by quoting his own masterpiece, Matisse explores how an artist’s past can live productively in the present, transformed by new contexts and new pictorial problems.

Conclusion

In “Nasturtiums with ‘The Dance’” Matisse presents an interior powered by the idea of dance. The studio becomes a chamber in which color performs, line sings, and objects hold their ground with serene assurance. Dancers whirl in a cobalt cosmos while nasturtiums bloom on a yellow trestle; between them moves the viewer’s eye, testing and enjoying the ties that bind the elements. The painting’s achievement lies not in spectacle but in equilibrium. It offers a modern image of happiness constructed from pure pictorial means—a harmony of movement and rest, of monumental memory and domestic presence, of color that both anchors and uplifts.