Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

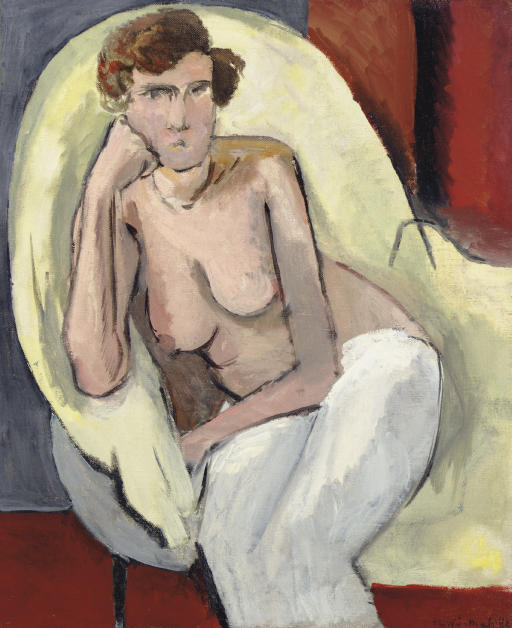

Henri Matisse’s “Naked Leaning” (1919) captures a private interval in the studio: a model sinks into a pale armchair, torso bared, elbow propped, eyes turned away in absorbed thought. The pose is familiar from classical nudes, yet the painting feels modern because of its frank simplifications, its compressed space, and the declarative force of color. A handful of tones—ivory, gray, wine-red, rose, and flesh—organize the picture like notes in a spare chord. The body is not polished into marble; it is built from planes and brushstrokes that retain the immediacy of looking. Matisse places sensation over finish, rhythm over description, making the painting read as both figure and architecture, both intimacy and design.

Historical Context: A Postwar Studio And The Opening Of The Nice Period

Painted in 1919, the work arrives on the cusp of Matisse’s Nice period, when he turned to interiors drenched in Mediterranean light, odalisques, and ornamental screens. Europe had just emerged from the First World War; artists sought steadiness in domestic subjects and timeless genres. The nude was a natural site for renewal, offering a lineage back through Ingres and Titian even as it could bear the innovations of modern color and contour. In “Naked Leaning,” the artist tempers the earlier blaze of Fauvism without relinquishing its core: color as expressive structure. The palette quiets, the light softens, but the essential conviction remains that painting can distill life to a few resonant relations.

Subject And Pose: Leaning As Thought

The model’s left arm props her head; her right hand slips toward the hip. The lean compresses one side of the torso, letting the breast drop naturally and creating a diagonal line from elbow to knee. This diagonal animates an otherwise still moment and gives the composition its pulse. The face, turned slightly away, is withheld just enough to keep the encounter from feeling theatrical. We are granted proximity but not performance. The pose reads as thought rather than display—a pause between shifts of attention, a human being at rest in the presence of another human being who looks and paints.

Composition: Ovals, Wedges, And A Stage Of Color

The armchair is a great pale oval; within it, the body forms a second oval defined by shoulder, elbow, flank, and knee. These large curves are braced by angular wedges: the white drapery over the legs creates a sturdy triangle; the dark panel behind the chair is a vertical bar; the floor’s wine-red field forms a strong horizontal base. Matisse builds the composition like a stage set of blocks and arcs, giving the figure both cradle and counterweight. Cropping is decisive: the body is cut at the shins and again at the top of the head’s halo of hair, heightening immediacy and preventing academic distance.

Color Strategy: A Quiet Fire

The painting’s power rests on the poised conversation between warm and cool. Flesh tones run from rosy beige to cooler gray-pink; the chair’s pale lemony ivory cradles the torso with a bath of light; the background oscillates between dove-gray and deep red. That red—neither crimson nor brown—radiates across the lower portion like a carpet of heat, while the gray wall cools the stage and pushes the figure forward. Matisse avoids intricate local color; instead he tunes a few fields until they vibrate together. The effect is a quiet fire: restrained, but glowing from within.

Drawing And Contour: The Calligraphic Edge

Matisse’s line moves like a wrist-written sentence. Contours swell and thin, sometimes closing a form, sometimes leaving it open for the paint to complete. The outline of the left arm is a single continuous phrase; the jaw is indicated by a clipped curve; the chair’s rim is reinforced with dark accents that keep the pale cushion from melting into the wall. These lines are not afterthoughts; they are structural. They hold the broad color areas in tension, letting the body remain solid without heavy modeling. Where Ingres used drawing to polish, Matisse uses it to breathe.

Modeling And Surface: Planes Instead Of Anatomy

Volume is suggested by planar turns rather than anatomical minutiae. The breast is a soft oval shaped by temperature shifts; the abdomen is a cool plane that meets the warmer flank; the cheek catches a flat, pale light that refuses elaborate shadows. Brushstrokes remain legible, especially in the chair and drapery, where their direction helps define form: verticals on the cushion’s outer rim, diagonals across the cloth on the legs. This painterly surface keeps the image in the present tense; one senses decisions made and left visible, a record of looking as action.

Space And Depth: Shallow, Pressurized, Intimate

The room is compressed into a shallow box. A vertical dark panel at right and a gray plane at left pinch the space around the chair, while the red floor pushes the figure toward us like a rising platform. There is just enough recession to keep the chair grounded—its back overlaps the wall—but not enough to dissipate intensity. This shallow depth is quintessentially modern: the painting acknowledges both the reality of a room and the flatness of the canvas that hosts it.

The Chair As Second Body

The chair does more than support; it participates. Its crescent of pale upholstery echoes the curve of shoulder and hip, making a duet of human flesh and padded furniture. In several places the chair’s rim and the body’s contour run in parallel, like two lines in harmony. The upholstery’s cool light softens the body’s warmth, and the dark seam along the chair’s edge frames the torso as if with a drawn parenthesis. The chair becomes a second body—pliant, sheltering, answering the figure’s arcs with its own.

Eroticism And Reserve

“Naked Leaning” is direct without being prurient. The model’s nudity is frank, yet the averted gaze and the emphasis on structure temper the erotic charge with decorum. Matisse refuses sensational detail: no luxuriant textiles, no props to stage an exotic fantasy. Instead he asks whether emotion can be carried by balance—how weight on an elbow, the fall of a breast, and the curve of a chair can register desire, fatigue, and presence. The result feels both intimate and respectful, a nude that acknowledges the viewer while preserving the sitter’s inner life.

A Dialogue With Tradition

The leaning nude has deep roots in European painting—from Venetian reclinings to Ingres’s odalisques. Matisse keeps the tradition’s essential contrapposto but strips away the ornament. The figure’s dignity comes not from jewels or drapes but from compositional poise. At the same time, the broad planes evoke Cézanne’s lessons in construction, while the reduced palette and decisive contour carry the memory of Fauvism in a tempered key. The painting speaks to the past without bowing to it, translating the classical nude into a modern syntax of surface and shape.

The Face: Structure Over Portraiture

Matisse withholds particularity in the face, avoiding the traps of anecdote. Features are simplified into interlocking planes: brow and cheekbone as cool facets, lips a small horizontal, eyes as focused shapes under a firm brow. The expression is ambiguous—pensive, perhaps mildly skeptical—a mood maintained by the compressed mouth and the slight pinch between brow and hair. By limiting detail, the artist lets the body’s larger rhythm carry character; the sitter is known through posture rather than through likeness.

Rhythm And Repetition: From Elbow To Knee

The painting is woven from echoes. The angular wedge of the bent forearm repeats in the angle of the thigh; the curve of breast and belly answers the chair’s arc; the diagonal from left elbow to right knee sets the composition’s main current, which is caught and steadied by the contrary diagonal of the drapery across the legs. These repetitions create musical coherence. The eye moves in smooth loops, returning again and again to the elbow—the hinge that organizes the body’s lean and gives the picture its name.

The Role Of Red

The wine-red floor is not background noise; it is the painting’s bass note. Against the cool grays and ivories it reads as body-heat diffused into space, a field of latent energy. By letting this red touch the lower edge of the white drapery and the chair’s base, Matisse makes heat interact with the cool planes, preventing the image from becoming pallid. The red’s saturation also anchors the composition, giving the heavy lower register needed to support the pale upper half.

Tactility And Material Weight

Matisse’s surfaces insist on the painting as object. The paint sits with slight thickness in the chair and drapery, thinner in the flesh, so that the sensation of materials is differentiated: plush cushion, crisp cloth, soft skin. The brush leaves its handwriting along contours, reminding us that a human hand translated another human presence into color and line. That insistence on tactility is ethical as much as aesthetic: it refuses the illusion that we are seeing the person herself, keeping the painting honest about its means.

The Body As Architecture

Although tenderly observed, the body is also a piece of constructed geometry. The torso reads as a trapezoid joining the wedge of thigh to the oval of shoulder; the head caps the structure like a modest cornice. This architectural clarity gives the figure weight and durability, countering the historical tendency to treat the female nude as vanishing spectacle. In “Naked Leaning,” the model is a built presence, a structure among structures, as solid as the chair and more commanding than the wall.

From Fauve Heat To Nice Calm

Compare this canvas to Matisse’s prewar “Blue Nude” or the brash interiors of 1908–11 and you can feel the temperature change. The earlier works explode with chromatic daring; this one radiates from a quieter core. Yet the continuity is real: flat color areas, black-brown contours, and the belief that simplification intensifies sensation. “Naked Leaning” exemplifies the artist’s ability to refine without retreating—to channel previous discoveries into a new, humane calm that would dominate the 1920s.

Time, Gesture, And The Present Tense

The painting holds a moment without freezing it. You can sense the next small motions: the shift of weight in the hips, the rub of fingers against cheek, the slide of cloth along the shin. Matisse achieves this by avoiding hard locks in the contours and by keeping edges slightly alive—especially around the head and elbow, where lines feather into surrounding paint. The moment is suspended, not stilled; the picture feels awake.

Looking Today

For contemporary viewers, the canvas offers a lesson in attention. It invites us to read a person not by facial expressiveness alone but by structure—how a body occupies space, how support and fatigue find balance, how heat and cool carve zones around a seated figure. The painting proposes that dignity can reside in the management of big relations: curve to wedge, pale to saturated, near to far. Its modernity lies less in shock than in composure, a confidence that feeling can be distilled rather than amplified.

Conclusion

“Naked Leaning” is a masterclass in clarity. Matisse sets a human body into a shallow architecture of color and line and lets a few decisions do the work. The chair embraces the figure without swallowing it; the red ground warms the scene without theatrics; the contour draws and releases with musical timing. What we are left with is not an anecdote but a condition—thoughtful rest—rendered with generosity and restraint. In the aftermath of upheaval, such poise counted as a kind of renewal. It still does.