Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

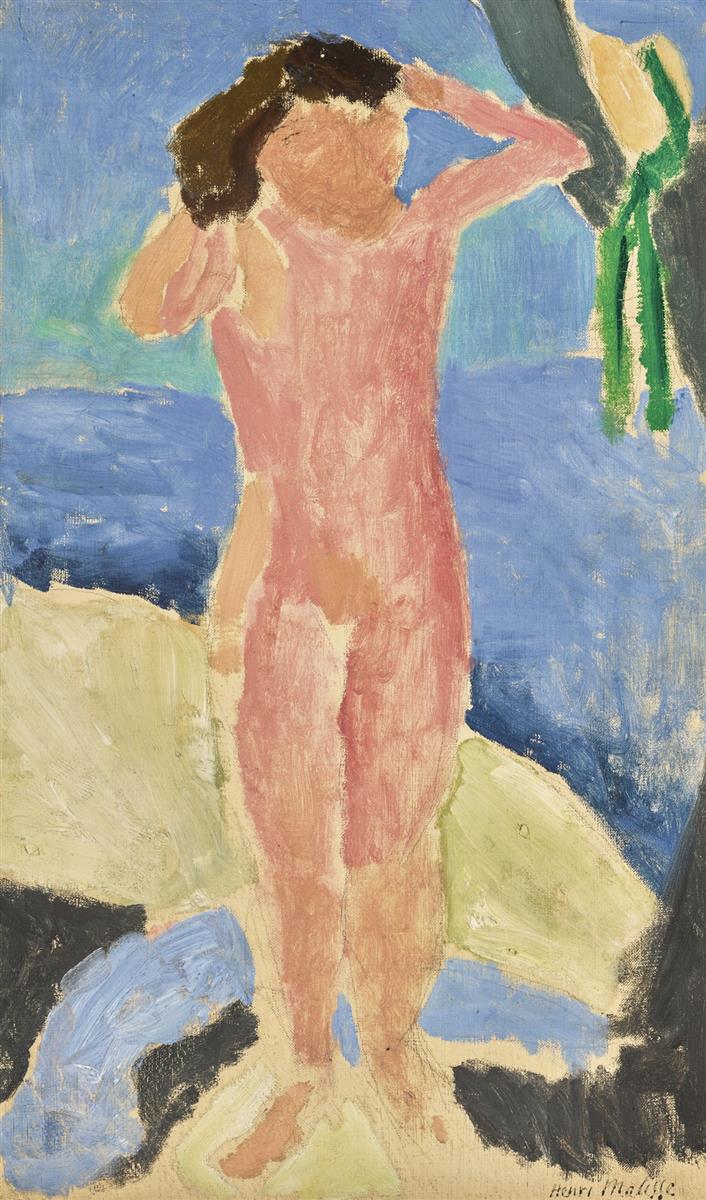

Henri Matisse’s “Naked by the Sea” (1909) is a compact, radiant experiment that reduces the classic theme of the bather to a handful of planes and colors. A standing nude, seen from the back, raises both arms to her hair while facing a blue expanse that reads as sea and sky. Around her, rock forms tilt in pale lemon, chalky green, and slate blue. The head is scarcely articulated, the limbs are simplified, and the contours soften into the surrounding air like chalk rubbed on stone. Matisse uses a narrow vocabulary—pink flesh, cool blues, sandy lights—to propose an image that is at once immediate and timeless. Rather than describe the world, the painting constructs it through rhythm, interval, and color. The result is a lyrical manifesto for his 1909 search for clarity: a modern pastoral where the body and the Mediterranean become a single, breathing structure.

Historical Context and the Mediterranean Turn

The year 1909 marks Matisse’s shift from the incendiary color clashes of Fauvism toward a calmer, architectonic language. He had already set down the path with large simplifications in works like “Dance I,” and he continued to refine a vocabulary in which color would perform the structural work once reserved for drawing and modeling. “Naked by the Sea” belongs to this moment of consolidation. The subject of the bather had deep roots for Matisse, intertwining with his attraction to the Mediterranean as a site of renewal. In the south he found a clarity of light that encouraged radical simplification. Rather than describing the particularities of a cove or a model, he distilled the experience of warmth, wind, and open water into zones of paint that feel inevitable. The painting’s extreme economy—almost a study in reduction—shows a painter confident that the fewest necessary notes can sing the strongest song.

Composition and the Architecture of the Figure

The composition is governed by a tall rectangle whose vertical orientation suits a standing body. The figure occupies the center, rising from the rocks like a column. Her raised arms form a small pediment that caps the vertical thrust and binds head to torso. Matisse avoids outline in favor of abutment: the pinks of the body meet the blues and greens of the surroundings with only the slightest jog of a soft, dragged edge. This decision keeps the form and the field in continuous conversation. The figure’s stance—weight on both feet, one hip subtly higher—generates a quiet contrapposto that enlivens the otherwise monumental simplicity. The diagonal of the rock shelf at the lower right and the slanted shoreline at left contribute counter-movements that prevent the central column from feeling inert. Everything is balanced, not by symmetry, but by measured pushes and pulls.

The Pose and the Motif of the Bather

By raising her arms to her hair, the model assumes a ritualized pose that reaches back to antiquity while remaining entirely modern. The gesture elongates the torso, opens the ribcage, and exposes the back’s long axis so Matisse can stabilize the entire composition with a single, unbroken vertical. The turned head, largely unmodeled, refuses portraiture, transforming the person into an emblem of bathing rather than an individual at a particular moment. This is characteristic of Matisse’s bathers across the decade: the body becomes a sign of vitality rather than a psychological case. The extreme simplification also invites empathy. Because details are withheld, we project ourselves into the posture and feel the stretch of the shoulders and the warmth of stone underfoot.

Color Architecture: Flesh Against Sea

Color does the structural work of perspective and modeling. The sea is a banded blue—deeper at the horizon, lighter near shore—laid in with horizontal strokes that slow and calm the upper field. The body’s pinks are complex: cool near the edges, warmer and more saturated along the spine and thighs, with small patches of light that indicate shoulder blades and the swell of the calf. These are not imitative highlights; they are relational notes that make the pinks breathe against the blues and ochres. Around the figure, Matisse sets pale, chalky greens and buttery yellows that function as warm stone under Mediterranean glare. The palette is limited, but the relationships are rich. Flesh vibrates against water; land cushions the color chord with matte lights; a few darker accents—the hair mass, pockets of black in the rocks—ground the whole.

Brushwork and the Presence of the Hand

The painting’s surface declares its making. The brush drags over rougher ground, leaving dry striations that read as sanded stone or wind across water. Elsewhere, paint is buttery and opaque, especially in the body’s central passages where strokes run vertically to affirm stance. Matisse does not smooth transitions; he lets adjacent fields meet with the minimum necessary mediation. Pentimenti are visible where a shoulder was nudged, a forearm trimmed, or the shoreline shifted. These traces do not signal indecision; they register the search for exact intervals. The candor of facture—scraped edges, resurfaced zones, thin slips of ground peeking through—keeps the picture alive at close range while preserving its serenity at distance.

Drawing by Planes Rather Than by Line

Although a few contours can be found at the outer edge of limbs, the dominant method here is drawing by planes. A cooler pink broadside meets a warmer pink’s edge; a chalky green pushes against blue to turn a rock; a pale wedge at the small of the back sets the spine into relief. The figure emerges not because Matisse has traced her silhouette, but because he has built the world of planes around her. This approach draws from his admiration for Cézanne’s bathers—figures constructed as interlocking facets—and from his own insistence that drawing and color are not separate tasks. In “Naked by the Sea,” every plane pulls double duty: it is both a hue and a piece of architecture.

Space, Depth, and the Shallow Stage

Depth is shallow yet convincing. The sea’s banding gives just enough recession to propose a distance without puncturing the surface. Rocks overlap in a few strategic places to establish near and far. The figure stands firmly in the foreground because the largest contrasts of temperature and value accrue around her. Perspective lines are few; the eye reads space mainly by stacking and by chromatic drift. This shallow stage is crucial to the painting’s mood. It holds the viewer close to the body and the immediate sensory facts—warmth, glare, breeze—while allowing the sea to remain a calm, continuous field.

The Mediterranean as an Idea

The blue expanse is not a named cove; it is the idea of the Mediterranean distilled into color. Matisse had long believed that the south offered a classical clarity unavailable in northern light. Here, he lets hue do what narrative usually does: locate the scene. A single blue, modulated by pressure and mixture, establishes a place as surely as any landmark. The ochres and greens of the rocks reinforce this, recalling chalk cliffs, scrubby vegetation, and sun-baked outcrops. Rather than catalog details, Matisse offers the sensation of a shore, trusting viewers to supply specifics from their own memory or desire.

The Ethics of Simplification

Simplification in this painting is not shorthand; it is principle. By removing facial detail and reducing anatomy to large, legible masses, Matisse invites us to read relations rather than incident. The back becomes an avenue for color modulation; the arms become arcs that lock the composition; the legs become long strokes that tether figure to ground. In the absence of descriptive fuss, the viewer attends to the picture’s true engine: the balance of temperatures, the cadence of shapes, the measured press of figure against field. Simplification here is also humane. It saves the model from objectification by refusing close-up exposure. The nude is monumental because she is rendered essential.

Kinships with “Dance” and the Bather Suite

“Naked by the Sea” is a close cousin to the monumental bathers and dancers Matisse pursued in 1909–1910. The body’s long, unbroken rhythms anticipate the chain of figures in “Dance,” while the restricted palette and shallow stage echo the laboratory conditions of those large canvases. Yet this painting retains an intimacy the larger works forego. Where “Dance” projects public ritual, “Naked by the Sea” preserves private time—an individual caught in a moment of unselfconscious adjustment after bathing. The two modes are complementary: one builds communal archetype; the other tests the strength of a single figure against the same language of planes and color.

Texture of Ground and the Role of the Canvas

The canvas tooth participates in the final effect. Thinly brushed passages allow the weave to sparkle through, especially in light rock areas and in parts of the sea. This sparkle becomes a visual equivalent of grit and salt in air. In thicker passages—spine, shoulder, hair—the paint compresses that texture, creating a tactile hierarchy that the eye reads as weight and nearness. Matisse’s sensitivity to how much of the ground to expose, and where, is part of his broader ethic of economy. He uses just enough material to deliver the sensation and no more.

The Body as Living Architecture

In this painting, the body is both organism and architecture. Its vertical axis provides the column around which the world arranges itself. Yet the soft edges and warm modulations prevent monumentality from hardening into stone. The figure feels vulnerable and strong at once: vulnerable in her bareness and anonymity; strong in her centrality and unembellished stance. This balance is the humanist core of Matisse’s project. He finds grandeur not in heroic action but in the simple fact of a body standing in clear light next to open water.

Process, Revision, and the Trace of Time

Evidence of revision appears in small halos where blue nips into pink along the arm and where pale rock planes lap up to the calves. These are the footprints of a painter weighing distances and rebalancing masses. The signature, slight and unobtrusive at the lower right, affirms that the painting is not just an image but a record of making. Time resides on the surface: earlier decisions show through later ones, and the final state respectfully includes their ghosts. The picture remains fresh because it preserves the steps that brought it into being.

Sensory Atmosphere and Emotional Tone

While the forms are sparse, the mood is palpable. The blue carries coolness and depth; the ochres feel sun-hot; the pinks hold the warmth of skin. The raised arms suggest the afterfeel of water and a small attention to self-care. Nothing is dramatic, yet everything is charged with the quiet intensity of being fully present. The emotional tone is serene, almost meditative. The sea is less a backdrop than a partner in this calm—a vast, steadying presence that makes personal time feel expansive.

Modern Classicism

“Naked by the Sea” belongs to Matisse’s modern classicism, a language that claims continuity with ancient ideals while shedding academic detail. The nude is an eternal subject, but here she is neither goddess nor allegory. She is a person reduced to the lines and planes that matter, presented with dignity in a world that is also reduced to its essentials. That combination—archetype without myth, simplification without emptiness—defines Matisse’s mature ambition and explains why paintings like this continue to feel contemporary.

Influence and Legacy

The lessons embedded in this small canvas ripple outward. Painters learned from its refusal of fussy modeling, embracing drawing by color planes. Designers absorbed its balance of vertical thrust and horizontal calm. Even photography and film echo its insight that clarity comes from a few strong relationships set with conviction. The bather motif would persist through Matisse’s Nice period, often in more opulent interiors; yet the fierce economy of 1909 underwrites those later canvases. “Naked by the Sea” proves that the essential can stand alone.

Conclusion

Henri Matisse builds “Naked by the Sea” from a bare minimum of means: a vertical body, a banded sea, sunlit rocks, and a disciplined palette. From these, he extracts a complete experience—of posture, light, heat, and the restorative freedom of water. Color constructs form; planes replace outlines; brushwork keeps air and flesh alive. The painting’s greatness lies in how decisively it chooses what to keep and how gracefully it lets the rest fall away. In doing so, it offers a durable image of human presence at the edge of the Mediterranean, where simplicity becomes a form of radiance.