Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

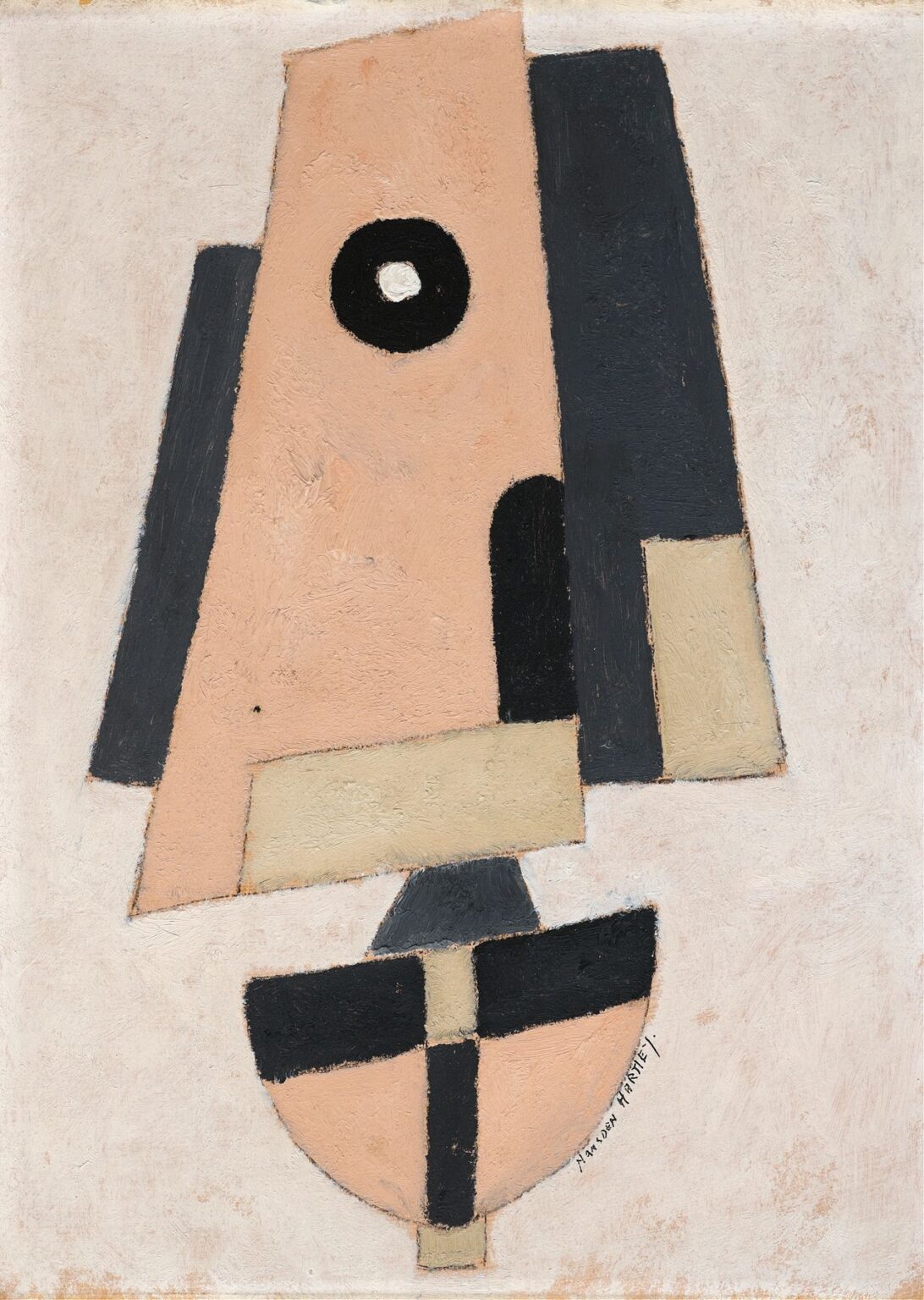

In Movement, Bermuda (1916), Marsden Hartley undertakes an audacious exploration of form, color, and abstraction, marking a pivotal moment in his artistic trajectory. Painted during his time in Bermuda, this canvas rejects direct representational cues in favor of geometric planes that evoke the rhythms and energies of an island seascape. Rather than depicting palm fronds or sandy beaches, Hartley distills his experience into a vertical arrangement of interlocking shapes—rectangles, ellipses, and circles—in a restrained palette of peach, black, and off‑white. Through this bold formal experiment, he channels not only the physical sensations of wind and wave but also the transcendent qualities of motion itself. Over the course of this analysis, we will examine how Movement, Bermuda synthesizes Hartley’s influences from Cubism and German Expressionism, his personal response to wartime displacement, and his quest for a new visual language that could capture the dynamism of modern life.

Historical Context

The year 1916 found Marsden Hartley undergoing profound personal and artistic transformations. Having left New York for Paris in 1912, he immersed himself in the avant‑garde currents of Cubism and Fauvism, yet the outbreak of World War I and the subsequent chaos in Europe compelled him to relocate to Bermuda. The island offered physical refuge and the promise of uninterrupted artistic exploration, but it also confronted Hartley with the dislocation wrought by global conflict. In Bermuda, he painted landscapes, marine views, and still lifes, gradually moving away from the representational toward abstraction. Movement, Bermuda emerged from this crucible, reflecting both the isolation of wartime refuge and the exhilarating freedom of tropical light and color. As Hartley strove to reconcile his American identity with European modernism, this painting crystallized his vision of art as a means of transcending the fractures of history.

Artist’s Evolution up to 1916

Marsden Hartley’s early career combined elements of academic realism with hints of the Symbolist and Post‑Impressionist styles popular in the United States during the first decade of the twentieth century. His move to Europe in 1912 exposed him to the avant‑garde circles of Paris, where he encountered Picasso’s Cubist experimentations and Matisse’s vibrant colorism. By 1914, Hartley had moved to Berlin, forming friendships with luminaries such as Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc of the Blaue Reiter group. These interactions fostered his interest in abstraction and the spiritual dimensions of color. The onset of war in 1914 disrupted his European sojourn, leading to a two‑year period in Bermuda that would see Hartley synthesizing his academic training with avant‑garde influences. Movement, Bermuda thus represents the culmination of his prior explorations and the beginning of his unique contribution to modern American art.

Visual Description

At first glance, Movement, Bermuda presents a vertical composition dominated by two large, overlapping shapes: a central peach trapezoid and a dark charcoal rectangle set slightly behind it. A smaller ivory trapezoid intersects the lower portion, while an oval form, bisected by a black cross‑bar, floats at the bottom edge. Near the upper center, a black circular disc houses a smaller white circle—an abstract sun or porthole. The off‑white background is rendered with a subtly textured, nearly monochromatic wash, allowing the central shapes to project forward with almost sculptural prominence. The canvas’s raw edges reveal hints of underpainting and canvas weave, reinforcing the work’s material presence. Despite the lack of literal landscape elements, viewers may sense the suggestion of sails, masts, and maritime horizons, conveyed through geometric abstraction.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics

Hartley arranges Movement, Bermuda according to a careful balance of vertical and diagonal axes. The central peach form tilts slightly to the left, while the charcoal shape behind it tilts gently rightward, generating a sense of tension and counter‑thrust. The ivory trapezoid at the base provides a horizontal anchor, counterbalancing the vertical thrust of the upper forms. This interplay of angles creates an implied rhythmic oscillation, reminiscent of the swaying masts and shifting sails of a vessel at sea. By compressing the spatial depth—eschewing realistic perspective—Hartley transforms the canvas into a dynamic stage where abstract elements interact like components of a musical composition. The viewer’s eye is guided along the folds and overlaps, evoking the continuous motion that the painting’s title promises.

Color Palette and Light

The restrained color scheme of Movement, Bermuda is integral to its expressive power. The central peach hue, close to a muted terra cotta or sun‑bleached stucco, contrasts with the deep charcoal and the pale ivory forms. These three dominant colors are modulated through textured brushwork: impasto in the darker areas, thin washes in the lighter ones. The off‑white ground, with its subtle undertones of ochre and pink, suggests ambient tropical light filtering through clouds or mist. There is no direct chiaroscuro; instead, Hartley relies on juxtaposition—light against dark, warm against cool—to animate the composition. This careful modulation of color evokes the sensory experience of Bermudian daylight, while preserving the painting’s abstract integrity.

Texture and Surface Treatment

On close inspection, Movement, Bermuda reveals a nuanced surface texture that testifies to Hartley’s painterly process. The background wash bears the irregular strokes of large brushes, leaving visible canvas weave and underscored edges. In contrast, the edges of the central forms are defined by thin outlines of darker paint, imparting a cut‑paper quality that reinforces the shapes’ autonomy. Within the shapes themselves, Hartley employs both dense impasto and scumbled underlayers, creating a sense of depth and materiality. The black circular disc, for instance, exhibits layered rings of paint that suggest concentric energy fields. These textural variations lend the work a tactile resonance, inviting viewers to consider the painting not only as an image but also as an object imbued with physical presence.

Formal and Geometric Structures

Hartley’s abstraction draws deeply on Cubism’s analytic dissection of form, yet he adapts these principles to create a visual language uniquely his own. The geometric structures in Movement, Bermuda—trapezoids, rectangles, ovals—are simplified, almost archetypal, yet they maintain a sense of relational complexity. The interlocking of shapes suggests both acceleration and deceleration, as if the forms expand and contract in response to unseen forces. The use of a circular motif—a black disk with a white center—introduces a counterpoint to the largely rectilinear vocabulary, adding a portal‑like reference or cosmic resonance. By subordinating literal depiction to pure form, Hartley invites viewers to experience the essence of movement rather than its concrete representation.

Symbolism and Thematic Interpretations

While Movement, Bermuda is primarily abstract, its formal choices carry symbolic weight. The central peach plane may evoke a mast or the hull of a ship, while the charcoal form behind could signify an accompanying sail or shadow. The ivory shape that intersects the base suggests the deck or foaming surf. Together, these elements create an allegory of maritime passage—a metaphor for Hartley’s own journey through war‑torn Europe to the relative isolation of Bermuda. The black disk with its white core could represent the tropical sun, a telescope aperture, or even a spiritual eye, alluding to Hartley’s interest in metaphysical themes. In this reading, the painting transcends mere aesthetic exercise to become an emblem of navigation—both geographic and existential.

Influence of Bermuda and Maritime Motifs

Bermuda’s archipelago, with its pastel-hued houses, translucent waters, and azure skies, left a profound impression on Hartley. Although the artist seldom indulged in direct landscape depiction, his Bermuda period paintings evoke the archipelago’s light and color through abstraction. Movement, Bermuda translates maritime motifs into geometric syntax: the vertical thrust of the central forms suggests ship masts, the overlapping shapes recall folded sails, and the circular motif hints at portholes or navigational instruments. This abstraction allows Hartley to capture the essence of seafaring energy without resorting to naturalistic detail. The painting thus stands as a testament to Bermuda’s role in catalyzing Hartley’s shift toward distillation of experience into pure form.

Relationship to European Avant‑Garde

Although Hartley remained geographically removed from the European epicenters of abstraction during his Bermuda sojourn, he maintained intellectual ties to Cubism, Futurism, and the Blaue Reiter group. The fragmented planes in Movement, Bermuda resonate with Picasso and Braque’s Synthetic Cubism, yet Hartley eschews collage or simulated textures in favor of direct brush application. His emphasis on motion and dynamic tension recalls the Italian Futurists, while his interest in spirituality and color fields aligns with Kandinsky’s Theosophical explorations. Hartley’s painting thus occupies a transatlantic nexus: it interprets European avant‑garde ideas through the prism of American sensibility and the luminous context of the Caribbean.

The Notion of Movement in Hartley’s Work

Movement was a central preoccupation for Marsden Hartley, evident in his earlier marine paintings and his later abstract canvases. In Movement, Bermuda, he literalizes this interest by orchestrating shapes that imply rhythmic flux. The slight tilts of intersecting forms, the contrast between stable horizontals and charged diagonals, and the counterplay of positive and negative space all coalesce into a visual choreography. This conception of movement is less about depicting motion itself than about evoking the sensation of continuous transformation—a metaphor for the artist’s own evolution and the world’s ceaseless change amid war and exile.

Comparative Analysis with Hartley’s Other Works

Movement, Bermuda can be contrasted with Hartley’s earlier representational works—such as his 1913 watercolor landscapes of Maine—to highlight the gulf between his academic approach and his later abstraction. Similarly, comparing this painting to his New York City visit works of the mid‑1910s underscores Hartley’s response to the urban milieu versus the insular calm of Bermuda. In later decades, Hartley would intensify his abstraction in works like Painting Number 51 (1919) and Canadian Journal watercolors (1930s), yet Movement, Bermuda remains singular for its serene yet dynamic geometry, synthesizing formal innovation with experiential immediacy.

Psychological and Emotional Resonances

At its core, Movement, Bermuda channels Hartley’s emotional state during a period of uncertainty. The painting’s balanced tension—between warm and cool colors, stable and dynamic forms—mirrors the artist’s oscillation between insecurity and creative liberation. The central shapes, though abstract, resonate with human gestures: the leaning trapezoid of peach seems to tilt forward in curiosity, while the upright charcoal rectangle maintains stoic resolve. This emotional duality invites viewers to inhabit the psychological space of displacement and discovery, feeling both the weight of war’s aftermath and the exhilaration of uncharted artistic possibilities.

Reception and Legacy

Although Movement, Bermuda did not gain widespread acclaim in Hartley’s lifetime, it has since been recognized as a critical juncture in his career and in the development of American abstraction. Scholars have lauded the painting for its seamless integration of European avant‑garde principles with the unique light and landscape of Bermuda. Exhibitions of Hartley’s work in the late twentieth and early twenty‑first centuries placed this painting alongside his Berlin and Maine periods, highlighting its role as both culmination and point of departure. Today, Movement, Bermuda is celebrated for its visionary approach to abstraction, its emotive resonance, and its testament to cross‑cultural exchange in modern art.

Conclusion

Marsden Hartley’s Movement, Bermuda (1916) stands as a masterful embodiment of the artist’s quest for a new visual language that could convey the rhythms of nature, the energies of modern life, and the emotional depths of wartime exile. Through a bold synthesis of geometric abstraction, nuanced color modulation, rhythmic composition, and textured surface treatment, Hartley distills his Bermudian experience into an emblem of motion and transformation. The painting’s interplay of form and symbolism, its dialogue with European avant‑garde currents, and its poignant psychological undercurrents ensure its place as a landmark in the history of American modernism. As viewers continue to engage with Movement, Bermuda, they are invited to contemplate the ongoing dance between stability and flux, the personal and the universal, that defines both art and life.