Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

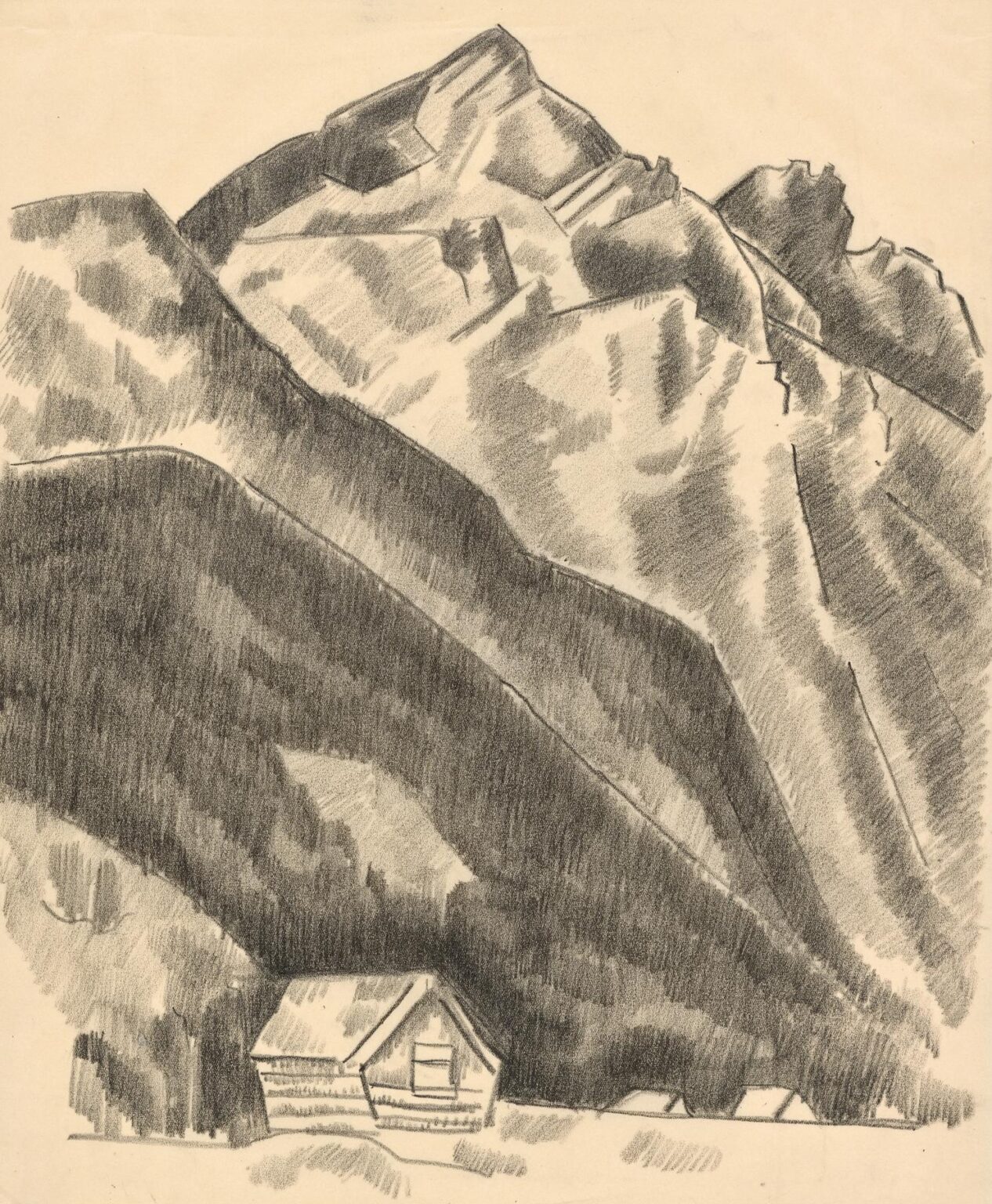

Marsden Hartley’s “Mountain Landscape” (1935) is a spare graphite drawing that compresses an entire cosmology into paper, pencil, and pressure. A massive ridge dominates the sheet, its facets caught in angled shade, while a humble cabin crouches at the base like a votive offering to geological magnitude. What looks at first like a straightforward study of peaks becomes, on slower viewing, a manifesto about scale, belonging, and the American modernist search for spiritual anchorage in nature. Hartley orchestrates contour, hatch, and negative space so that the mountain seems to rise and breathe, even as the drawing’s economy of means keeps the viewer acutely aware of the artist’s hand at work.

Returning Home: Hartley’s 1930s Quest For Place

By 1935 Hartley had resolved to be “the painter from Maine,” but his imagination roamed beyond the coast to interior immensities—Katahdin’s bulk, western mesas, alpine memories retained from European travels. “Mountain Landscape” belongs to this late period of consolidation, when he translated decades of experimentation in Berlin abstraction and New Mexico color into a lean, American idiom. The timing matters: the Great Depression had pushed artists to reconsider the local and the essential. Hartley, who had walked through grief, war, and ceaseless migration, found in the mountain a figure of permanence. Drawing it in graphite—portable, direct, unforgiving—signaled a desire for clarity and truth stripped of bravura.

Graphite As Instrument Of Structure And Atmosphere

Graphite lends itself to gradation, sheen, and immediacy. Hartley exploits all three. He lays down velvety fields with the side of the pencil, then scores crisp edges with the sharpened tip. Pressure shifts create a spectrum from whisper to bark, making shadowed valleys feel dense and sunlit planes light as breath. Unlike charcoal, graphite’s metallic luster can catch light at certain angles, a micro-echo of snow glare or mica in rock. This material nuance allows Hartley to suggest atmospheric clarity and the tactile grit of stone simultaneously. The drawing thus becomes both a map of pressure and a translation of mountain weather into touch.

Compositional Logic: Diagonals, Terraces, And The Shelter Below

The sheet is ruled by diagonals. A dark, sweeping slope cuts from mid left to lower right, creating a triangular swath of shadow that anchors the cabin. Above it, broken zigzags articulate the summit and its subsidiary peaks. These jagged profiles echo each other, producing a visual rhythm akin to a heartbeat rising and falling toward the apex. The cabin sits in the lower band, framed by the mountain’s descending curtain. Its roofline parallels the primary diagonal, integrating human architecture into geologic order. Hartley thereby avoids mere contrast between nature and shelter; instead, he composes them as interlocking parts of one design.

Contour As Carving: The Mountain Drawn Like A Sculptor

Hartley’s outlines are not timid tracing but decisive incisions. Where a ridge meets sky, the line bites with a weight that reads as rock edge. Where planes within the mountain meet, he often lets value changes carry the border, implying seams rather than announcing them. This sculptural approach—modulating between cut and merge—recalls his Berlin period’s bold contours, now repurposed to describe granite rather than emblems. The mountain is not an amorphous mass; it is a hewn body, a cathedral of planes assembled by tectonic thrusts and the artist’s analogous strokes.

Tonal Blocks And The Cubist Echo

Look closely at the shading: Hartley does not smooth graphite into seamless gradients. Instead he stacks short, angled strokes into tonal blocks. Each block corresponds to a plane catching a certain light angle, echoing Cubist modeling but softened by naturalistic intent. The result is a faceted mountain that still reads as mountain, bridging abstraction and observation. These tonal tesserae guide the eye over the surface, making the act of shading a pathfinding exercise. Hartley invites viewers to climb with their gaze, stepping from patch to patch like hikers negotiating ledges.

Negative Space And The Breath Of The Paper

Large sections of untouched paper surround and infiltrate the drawing. The sky is essentially blank, but its emptiness is charged: it stresses the peak’s height, gives the eye rest, and lets the mountain’s graphite weight feel heavier by contrast. Within the mountain, Hartley leaves small light pockets that read as snowfields or reflective rock. These voids are not indecision; they are oxygen. Just as mountaineers need air between exertions, viewers need visual silence between dense marks. Paper becomes atmosphere, and the unmarked becomes active presence.

The Cabin As Measure And Metaphor

Scale enters via the small, rectilinear cabin. Its minute windows and shingles humanize the scene, supplying a unit of measure against which the mountain’s enormity becomes palpable. But the cabin is more than a yardstick. It is Hartley’s surrogate, a sign of habitation, of choosing to dwell under overwhelming forces rather than flee them. Its placement at the mountain’s base evokes humility and resilience. The building’s alignment with the compositional diagonal hints at harmony: to live well, align yourself with the grain of the land. In a broader reading, the cabin is art itself—modest shelter built beneath the sublime, offering vantage and refuge.

Light As Narrative: Morning Crispness Or Snow-Glare Memory

We cannot pin a specific hour to the drawing, yet Hartley’s value scheme suggests high-contrast illumination, perhaps morning sun slicing across slopes. Light here tells a story: certain faces leap forward, others recess, implying passage of time across the mountain’s body. That narrative of light-on-form parallels remembrance—select parts of the past stand out, others dim. Hartley’s own memories of European Alps or Maine’s Katahdin might fuse here, illuminated by a present desire to make them his. Light functions as editing, revelation, and emotional spotlight.

Psychological Geography: Monumentality, Solitude, And Stoic Calm

Mountains are psychology externalized. Their mass suggests endurance; their silence, contemplation; their forbidding angles, challenge. Hartley has long used landscape as emotional proxy, and in 1935 he faced aging, financial stress, and historical upheaval. “Mountain Landscape” is stoic without being cold. The drawing’s calm tonal rhythm and orderly composition project acceptance. Yet the sharp summits and looming shadow hold tension. Solitude is palpable; no trail, no figure, only the cabin’s mute presence. This is the solitude Hartley cultivated—fertile, chosen, charged with creative focus.

Dialogue With Earlier And Later Works

Compare this drawing to his 1913 abstractions: the mountain’s planes mirror those colored shards, but here reduced to graphite values. Later, in oil paintings of Katahdin, Hartley will adopt thick outlines and saturated color; the formal bones visible in “Mountain Landscape” underpin those canvases. Conversely, the cabin anticipates the fishermen’s houses of his coastal scenes. The drawing is thus a crossroads, binding Hartley’s emblematic past to his place-based future. It proves that even minimal media can carry his characteristic amalgam of symbol and structure.

American Modernism And The Ethics Of Simplicity

In the mid-1930s, American art oscillated between social realism and abstraction. Hartley forged a third path: essentialized realism. “Mountain Landscape” embodies an ethic of simplicity—use what you have, say only what matters, let line and value speak. This approach resonates with transcendentalist roots and Yankee pragmatism. It also forecasts later minimal and hard-edge landscapes where reduction equals revelation. Hartley demonstrates that modernism need not abandon subject to achieve formal innovation; it can discover modern form inside the subject’s truth.

Process Made Visible: The Artist’s Hand As Seismograph

Nothing here is overblended. Each hatch mark records a minute decision: darker here, lighter there, stop, lift, rotate. The drawing is a seismograph of attention. One can sense Hartley’s hand moving steadily, adjusting pressure like a climber testing footholds. Erasures, if any, are minimal; confidence governs. This transparency of process invites empathetic looking: we follow, understand, even mimic the motion. The drawing becomes instructional—not didactically, but physically—teaching us how to build solidity with repetition and restraint.

The Ethics Of Looking: Reverence Without Romantic Fog

Romantic mountain imagery often dissolves in mist and drama. Hartley denies vapor. His clarity is reverent but unsentimental. He neither sentimentalizes the cabin nor demonizes the massif. He observes and synthesizes. This ethical stance—respecting the mountain’s otherness while finding kinship—aligns with emerging ecological consciousness. The drawing says: behold, measure yourself, dwell humbly. In its quiet way, it models a sustainable gaze.

Memory, Translation, And The Act Of Recollection

The title’s generic breadth, “Mountain Landscape,” suggests a composite rather than a specific peak named. Hartley is translating remembered forms into archetype. Graphite’s grayscale assists: freed from color’s specificity, the mountain becomes an essence. Recollection edits; Hartley’s marks are those edits. The drawing thus stages memory’s mechanics: selection, emphasis, omission. Viewers participate by projecting their own mountain memories into the template.

Legacy And Contemporary Resonance

Today, when drawing is often eclipsed by digital immediacy, Hartley’s graphite sheet feels radical again. Its slowness, its attention to value, its trust in minimal tools resonate with contemporary desires for tactility and mindfulness. Artists exploring the boundary between abstraction and representation can find in “Mountain Landscape” a masterclass on how to facet reality without breaking it. Environmental artists can see a precedent for honoring landforms without spectacle. The work’s modest scale and medium also democratize greatness: you do not need a mural to speak monumentally; you need conviction and a pencil.

Conclusion

“Mountain Landscape” distills Marsden Hartley’s mature vision into graphite geometry. The towering ridge, the nested planes of tone, the small steadfast cabin—together they enact a drama of endurance, humility, and form. Hartley proves that drawing can be both analytical and devotional, that a mountain can be both rock and symbol, that modernism can be both rigorous and rooted. Long after the initial glance, the sheet continues to reveal its balances and tensions, inviting viewers to climb its marks, rest in its blankness, and perhaps build their own inner cabins beneath whatever mountains they face.