Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

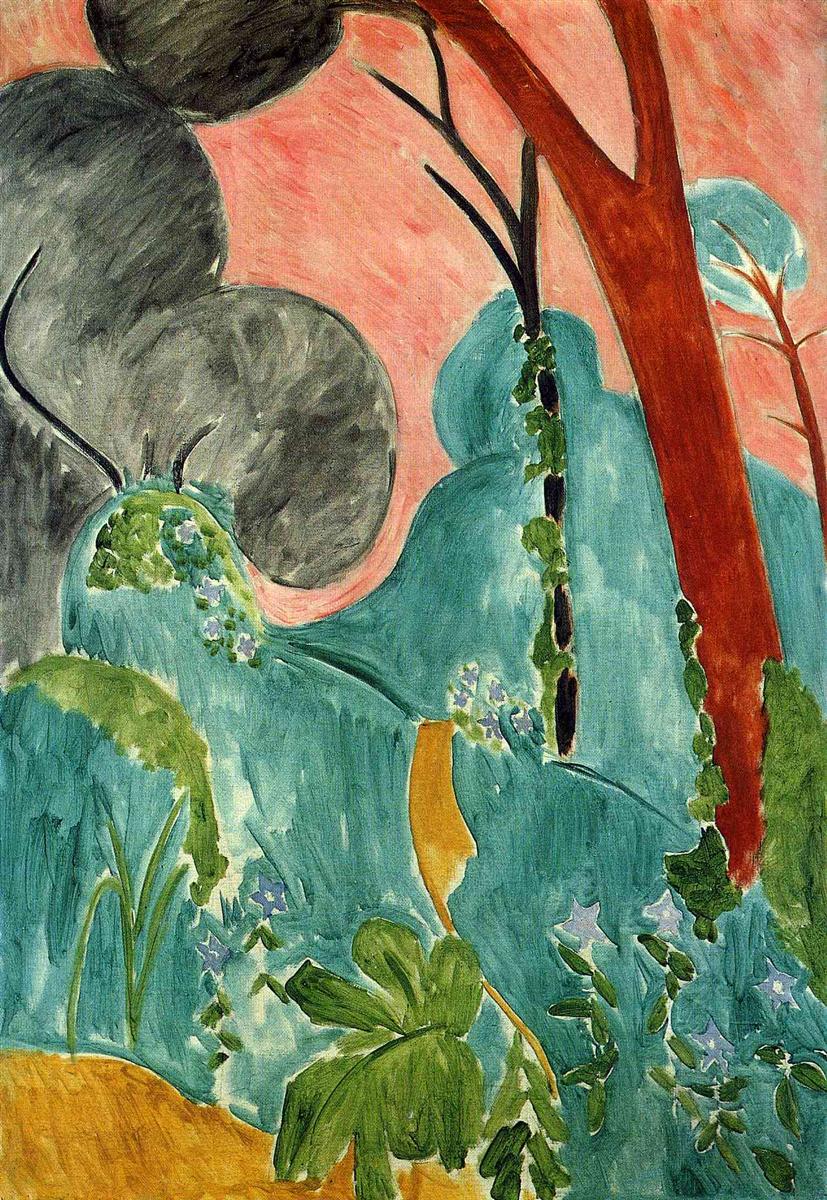

Henri Matisse’s “Moroccan Garden” (1912) captures the sensation of a garden seen for the first time under blinding North African light. Rather than cataloging leaves and branches, Matisse distills the experience into buoyant color planes and elastic contours. A salmon-pink sky presses forward like a warm wall; pools of turquoise-green describe mounded foliage; a rust-red trunk slices vertically at the right; soft gray disks swell like shade trees or passing clouds. The entire surface breathes with the paradox Matisse loved: a world reduced to a few signs that nevertheless feels abundant, living, and specific.

Historical Context

Painted during Matisse’s first Moroccan journey, “Moroccan Garden” belongs to the moment when he sought a purer, more architectural color than he had used in earlier Fauvist works. Tangier offered just such a laboratory. Whitewashed walls, saturated skies, and the flat clarity of midday turned shadows into planes and simplified forms at a glance. Matisse’s Moroccan pictures from 1912–13 show a decisive shift toward broad fields of color, shallow yet convincing space, and a decorative unity derived from Islamic gardens and courtyards. This canvas records that fresh encounter: the subject is a garden, but the deeper subject is a newly clarified way of seeing.

What the Painting Shows

The composition is not a literal botanical study. It offers a set of emblematic forms—rounded mounds of foliage, tree trunks, vine strings, starry blossoms, a gold path—that together evoke a small, lush enclosure. The gray, cloudlike circles at left can read as dense canopies or shaded parasols; the turquoise swells imply layered hedges; the red trunk and black branchlets give the scene an anchoring spine. A ribbon of ochre winds through the greenery like a sunlit path. The garden is less a place one could map than an environment of temperature, aroma, and quiet movement.

Composition and Structure

Matisse organizes the picture as a choreography of opposing vectors. Most volumes are rounded and swelling; against them stand two emphatic verticals—the red trunk at right and the black sapling behind it. The left side is heavy with three stacked gray disks, while the right side is lighter, punctuated by thinner stems and scattered star-flowers. The central area is a series of overlapping green masses crossed by a narrow ochre path that points upward, keeping the eye in motion. The composition is asymmetrical yet balanced, like a garden designed to feel spontaneous while obeying an unseen plan.

Color Architecture

Color carries the meaning. The turquoise that dominates the foliage is neither purely naturalistic nor arbitrary. It is a cool counterpart to the warm pink of the sky; together they establish a complementary pulse that animates the surface. The red tree trunk does more than depict bark; it sets a vertical flare that holds its ground against the surrounding cools. Spots of pale blue-violet in the flowers echo the sky’s coolness while gently standing out from the green. The ochre path bridges warm and cool zones, suggesting sun that has soaked into the ground. This interlocking structure of warm and cool makes the painting feel both fresh and stable.

Brushwork and Surface

The paint handling is relaxed but decisive. In the turquoise fields Matisse allows the bristles to leave a breathable texture, so underlayers flicker through and the greenery seems to shimmer. Edges are often softened or left ragged, letting the white ground articulate the boundary—a method that fuses drawing with painting. The red trunk is brushed more densely, asserting its weight. The gray disks at left carry soft, circular strokes that make them swell without resorting to tonal modeling. Everywhere the surface reveals the painter’s hand while maintaining the clarity of large shapes.

Space Without Conventional Depth

There is little linear perspective here. Space is created by overlaps and by the stacking of color zones. The pink sky is brought forward rather than pushed back, denying a deep horizon and turning the whole garden into a shallow, theatrical set. This is deliberate. Matisse wants the viewer to experience the garden as a tapestry of sensations laid upon a flat surface. The sense of depth that remains—the path that seems to slip between mounds, the vine that creeps along the red trunk—results from the way forms interlock, not from vanishing points.

Light of Morocco

The color decisions are inseparable from the climate in which Matisse worked. Moroccan light at midday can obliterate half-tones and turn shadows into simple slabs. “Moroccan Garden” bears that stamp: the leaves do not gradate smoothly from light to dark; they flip between planes of turquoise and mint. The sky is not feathered with atmospheric blue; it is a solid, sun-warmed pink, as if light reflecting from surrounding walls has colored the air. The painting gives us the sensation of stepping from shade into a courtyard where color seems to radiate its own heat.

Ornament and Motif

Islamic gardens emphasize pattern, water, and enclosure. Matisse translates that sensibility into pictorial terms. The repeated mounds function like a vegetal pattern; the vine that climbs the trunk reads as a decorative border; the small star-shaped flowers are arranged like textile motifs. Yet nothing becomes stiff. Each motif is adjusted to its neighbor so that ornament merges with organic growth. The painting proposes that decoration is not opposed to nature; it is nature perceived through a mind tuned to rhythm.

Drawing as Arabesque

Matisse’s line is spare but eloquent. The vine on the trunk is a string of small, leaf-shaped ovals, quick and musical. The black branch rising behind the trunk is a calligraphic flourish that opens the picture vertically. The ochre path is a single, winding stroke that slips between masses like an improvised melody. Even where no contour is drawn, the meeting of two colors creates a soft edge that reads as a line. The whole image can be traced with the finger as a continuous arabesque, a hallmark of Matisse’s mature style.

Rhythm and Movement

Although nothing overtly moves, the painting hums with slow momentum. The mounds rise and fall like breathing; the vine climbs; the path insinuates forward; the gray disks gather and release pressure at the left edge. These rhythms lead the eye from one zone to the next without interruption. Matisse achieves this flow by repeating curves at different scales and by allowing edges to remain porous. The result is a garden that seems to grow while you look.

Economy and Suggestion

One of the painting’s pleasures is how much it accomplishes with how little. A sliver of black inside a turquoise mound suddenly reads as a deep crevice. A quick stripe of mint turns a swell of foliage into two overlapping layers. The small violet star-flowers are no more than cross-shaped touches with white halos, but they conjure blossoms, aroma, and season. Matisse trusts the viewer’s capacity to complete forms and to feel their presence without descriptive detail.

The Garden as Idea

Beyond botany, the garden here is an image of calm enclosure. It is neither a vast landscape nor a windowed studio but a place of refuge bounded by color. The pink sky functions like a surrounding wall; the mounds form internal partitions; the path offers quiet passage. In many cultural traditions, the garden stands for order cultivated from nature. Matisse’s version suggests order achieved through color, where harmony arises not from trimming plants to a shape but from tuning hues so that they breathe together.

Dialogues with Other Works

“Moroccan Garden” converses with interiors and courtyards from the same period, such as arched doorways and kasbah thresholds where blue and red play opposing roles. It also anticipates later Nice-period pictures in which screens of foliage or patterned textiles flatten space and intensify color. Compared to the monumental studio pictures of 1911, this garden feels looser and more atmospheric, as though the discoveries of those disciplined canvases have been released into open air.

Relationship to Decorative Arts

Matisse admired textiles, tiles, and carpets for their ability to transform space through pattern. In this canvas, color fields act like pieces of cloth pinned to a wall. The repeated mounds could be read as appliqué shapes; the vine resembles an embroidered border. Importantly, the decorative impulse never becomes mere surface play. The garden’s structures—trunk, path, hill—remain legible. Matisse grafts decoration onto structure so that the painting reads both as a place and as a textile-like arrangement.

Emotional Tone

The prevailing feeling is one of warm serenity. The pink sky bathes the scene in a diffuse glow; the greens are cool but inviting; the red trunk, though assertive, is not alarming but vital. Nothing is stormy or dramatic. Even the gray disks carry the softness of shade rather than the threat of storm clouds. This emotional clarity stems from the tuning of color intervals. Each hue finds its partner and its foil, producing a stable yet lively accord.

Process and Revision

Close looking reveals subtle adjustments. In places where turquoise meets pink, a thin rim of white ground remains, sharpening the edge while letting air in; elsewhere, Matisse drags one color over another, creating a soft seam. The ochre path appears to have been edited, leaving a faint ghost of its earlier route. These traces of change are not distractions; they testify to a process of searching for the simplest, most resonant arrangement.

Nature, Culture, and the Red Trunk

The red trunk deserves special attention. Its color is striking, almost artificial, yet branches and ivy tether it to the garden’s living system. It becomes a hinge between nature and culture, a living form that also functions as a constructed column within Matisse’s architecture of color. The decision to paint it red is not arbitrary. Red is the complement of green; by giving the trunk that hue he locks the garden’s cool abundance to a warm pillar. The trunk is a support—botanical and pictorial.

The Painting’s Modernity

In 1912 painting could proceed by analysis, as in Cubism, or by synthesis, as in Matisse’s approach here. Rather than fracture forms into facets, he fuses them into large, legible shapes. Rather than model volumes with light and shadow, he lets color edges define them. The modernity of “Moroccan Garden” lies in its confidence that a few well-chosen relations can carry the experience of a place more powerfully than a mass of detail. This economy, far from decorative superficiality, is a hard-won clarity.

Why the Work Matters

“Moroccan Garden” matters because it distills a new way of inhabiting the world through painting. It shows how travel can yield not exoticist inventory but structural insight: the recognition that certain climates reduce experience to vivid zones of light and shade, warm and cool, wall and foliage. It demonstrates how a painter can honor nature while embracing the flatness of the canvas, making space and surface collaborate rather than compete. Within Matisse’s oeuvre, it stands as a key step toward the later cut-outs, where color becomes a literal shape and gardens are composed from leaves of painted paper.

Conclusion

Across its surface, “Moroccan Garden” keeps multiple truths in play. It is a garden one could almost walk through and a textile one could almost hang; it is a memory of a Moroccan courtyard and a manifesto about color’s power. Pink air presses forward; turquoise mounds breathe; a red trunk stands like a warm column of life. With minimal means and maximal sensitivity, Matisse composes a space of repose where the eye lingers and the mind brightens. The painting invites a simple act that is never simple: to look long enough for color to become form and for form to become feeling.