Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

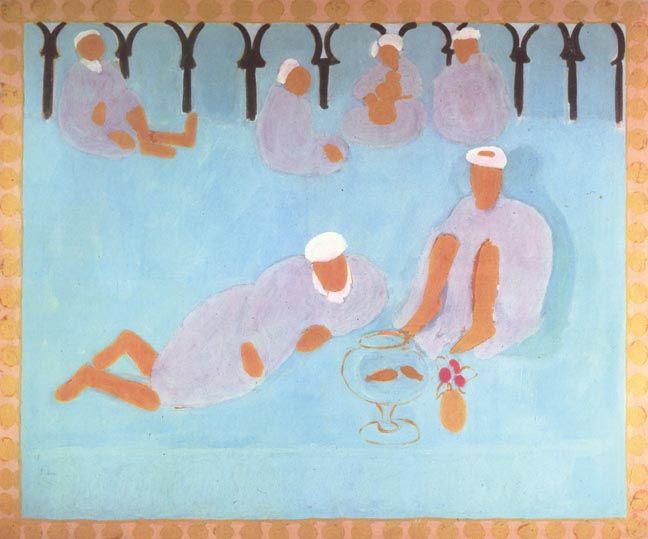

Henri Matisse’s “Moroccan Café” (1913) condenses the social ease of a public gathering into a luminous, carpet-like field of color. A handful of seated and reclining figures, simplified to rounded robes and small caps, float across an expanse of cool blue. A trellis of dark arches caps the scene like a frieze; a sandy, patterned border encloses it like a woven frame. Near the foreground, a glass bowl and a tiny vase with flowers punctuate the calm. Nothing is described in detail, yet the atmosphere is unmistakable: shade, conversation, waiting, the gentle drift of a warm afternoon. Matisse’s subject is not portraiture or anecdote but the very idea of sociability, translated into the decorative logic that governed his most innovative work.

Historical Moment

“Moroccan Café” belongs to the cycle that Matisse produced after two long stays in Tangier in 1912 and early 1913. The shock of North African light—white sun, blue air, planes of shadow that looked like color rather than gray—pushed him to reduce form to large, unmodulated areas and to rethink how a painting could be both a window and a patterned surface. In Morocco he also encountered Islamic architecture and ornament, where repetition, geometry, and calligraphic silhouette create order without perspective. The café, a space of pause and community, gave Matisse a subject that aligned with his desire for “balance, purity, and serenity.” This painting is one of the clearest distillations of that desire: a scene where the world becomes a tapestry of relations.

First Impressions and Visual Walkthrough

The canvas reads at a glance as a pale, airy rectangle set inside a sandy border. Within the blue field are figures simplified to lavender robes, warm terracotta hands and faces, and crisp white caps. Some sit upright; one reclines along the lower left; a small cluster gathers in the back as if in quiet conversation. Across the top edge, a row of dark, forked arches suggests a railing or screen. In the foreground to the right, a glass bowl—only a few contour lines and two orange shapes suggesting fruit—sits beside a small vase with a splash of red flowers. Nothing casts a hard shadow; bodies do not press against the ground; yet the scene feels anchored. The border acts as a floor and wall at once, the way a carpet defines a room.

Composition as Stage and Frame

Matisse organizes the painting like a portable fresco. The sandy border, dotted with soft circular marks, operates as a self-contained frame and as a visual echo of tiled thresholds and courtyard mosaics. Inside that frame, the blue field is nearly uniform, interrupted by gentle transitions that keep it breathing. The figures are distributed like notes on a staff: three small ones along the top, a central pair anchoring the foreground, and the reclining figure balancing the left. The dark arch frieze compresses the space and prevents the figures from drifting, while the objects near the right foreground anchor our eye in the immediate present. The entire design is legible at once, yet it rewards slow scanning; the eye traces from border to border as one would follow the repeat of a textile.

Color Architecture and Atmosphere

Color does the structural work. The dominant blue—cool, milky, and slightly varied—creates a sensation of shade and air. Against it, the sandy border and the ochre accents in faces and hands supply warmth, implying sun just beyond the picture’s edges. Lavender garments mediate between cool and warm, keeping the palette from splitting into two camps. White appears only where needed—caps, collars, small highlights in the bowl—and reads as concentrated light. Black, reserved for the arch frieze, provides the strongest graphic contrast and stabilizes the otherwise vaporous field. With only these few hues, Matisse builds not just a scene but a climate.

Pattern, Ornament, and the Café Setting

The arch motif at the top and the dotted border around the entire field are not decorative afterthoughts; they define the café as a patterned space. The arches hint at ironwork or mashrabiya screens that filter light and create privacy. The border’s repeated dots are like lozenges on ceramic tiles or stitches on a woven edge. Together they convert the painting into something that behaves like an object—a panel, a carpet, a wall hanging—that could live within an interior. Matisse’s café is not just a place people occupy; it is an ornamental structure that orders their presence.

Figures as Signs

The people in “Moroccan Café” are not individualized portraits. They are glyphs—a head, a robe, a gesture of a hand—reduced to their most legible shapes. Yet the reduction is not cold. Each figure’s pose suggests a different tempo: the recliner’s long diagonal reads as leisure; the central seated figure’s verticality suggests alertness; the back group forms a murmured chord of conversation. Matisse uses negative space to articulate these postures; the blue around each body is as important as the body itself. What might sound like a limitation—few details, few tones—becomes the source of eloquence. The viewer supplies the hum of voices and the clink of glass.

Space Without Perspective

Traditional perspective would place a horizon, converge lines, and create measurable recessions. Matisse declines all three. Space is conveyed through overlap, scale, and placement within the field. The back cluster is smaller and floats nearer the arch band; the foreground pair is larger and sits lower; the reclining figure crosses the lower edge and creates a near diagonal. The glass bowl and little vase are unambiguously frontal, their bases aligned with the border, establishing a shallow plane at the picture’s front. The result is a space as calm and navigable as a courtyard: shallow, coherent, and suffused with light.

The Language of Objects

Matisse often uses small still-life elements as tuning forks for a composition. Here the glass bowl—two oranges suspended in a clear contour—acts like a quiet gong of transparency amid opaque color. The small vase with pink blossoms, placed beside it, adds a vertical accent and a touch of ceremonial grace. These objects do not announce a narrative, yet they ground the painting in hospitality: fruit to share, a flower to delight. They also test how little information is needed to evoke volume; two or three lines around an opening and a stem are enough for the mind to complete a vessel.

Brushwork and Surface

Although the picture reads as flat, the surface is varied. The blue field is brushed in broad, slightly diagonal passes, leaving faint ridges that create a soft current. The lavender garments are scumbled so that hints of blue show through, binding figures to ground. The border’s dots are dabbed, their edges irregular, which keeps the frame from becoming mechanical. The frieze at the top is painted more crisply, as if its severity were necessary to keep the airy field in order. Everywhere the handling is light, closer to fresco or gouache than to oil’s modeled depth, appropriate to a subject of cool shade and rest.

Dialogue with Fauvism and Cubism

The painting owes something to the Fauvist conviction that color can stand on its own, but the momentary, vibrating brush of 1905 has given way to a more considered decorative plane. In relation to Cubism, “Moroccan Café” offers a parallel modernism. Instead of cubist fracture and analytic forms, Matisse proposes a shallow architectural stage where patterns and silhouettes do the work of structure. Space is modern not because it is dismantled, but because it is acknowledged as a flat surface with its own laws. The café becomes a manifesto for a different path: clarity, order, and an art that can live happily on a wall like a textile.

Islamic Aesthetics and the Ethics of Looking

Matisse admired Islamic art for its non-narrative richness and for how it treated ornament as thought rather than as embellishment. “Moroccan Café” honors that sensibility. The arch frieze is calligraphic rather than mimetic; the border reads like a repeat one could trace with a fingertip. The ethical stance follows: the painting avoids exoticizing detail and instead grants the figures dignity through compositional centrality and calm. They are not props or curiosities; they are the reason the pattern exists. The work translates an encounter into a language that respects both the painter’s discipline and the integrity of a shared public space.

Time, Rhythm, and Sound

The picture feels quiet, but not static. The repeated caps and robes set up a gentle beat; the reclining figure introduces a syncopation; the little back-row group hums like a soft choir. The bowl and vase punctuate the foreground like percussion. Because there is no cast shadow and no single light source, time seems suspended—an afternoon stretched into a timeless noon. Matisse’s rhythm is musical rather than cinematic; it does not tell a story, it sustains a mood.

From Scene to Interior

Matisse often thought of paintings as furnishings for a room—objects that could create an atmosphere as a textile or screen might. “Moroccan Café” makes that ambition explicit. The sandy border turns the canvas into a portable architectural panel. One can imagine it hanging within a modern interior, casting a blue haze of calm over a wall, the way a window does. The café, a space for rest, becomes a painting that performs rest in the room where it hangs.

Anticipation of the Cut-Outs

The simplified silhouettes and the emphasis on flat, unmodulated color make “Moroccan Café” feel like a precursor to Matisse’s paper cut-outs of the 1940s. The figures are already close to the cut-out language—shapes defined more by edge than by modeling, placed in a field that reads as a single chromatic atmosphere. The arch frieze could be cut paper; the border could be stenciled. The painting shows Matisse discovering that the strongest forms often appear when description is shed and only relations remain.

Leisure and Community

Cafés host both solitude and togetherness, and Matisse captures that duality. The figures share a ground and a climate, yet they keep their own gentle distances. The space feels public but not crowded, communal but not staged. The reclining body invites the viewer in; the seated pair offers company; the back group leaves room for one to listen rather than speak. In a moment when European modernism often courted agitation, Matisse chooses repose as a radical value.

Reading the Border

The border deserves a final, close reading. Its sandy color relates to the earth and to sun-warmed walls; its dotted rhythm carries the eye around without insisting on itself. It is the painting’s threshold, the edge where interior and exterior meet. Cross it, and the cool blue breath begins. Land at it again, and warmth returns. The border teaches how to look at the whole: move slowly, accept repetition, let color do the thinking.

Legacy and Place in Matisse’s Oeuvre

“Moroccan Café” sits near the center of Matisse’s lifelong effort to marry painting with the decorative ideal. It keeps company with the Tangier windows and with the portraits of Moroccan sitters from the same period, sharing their preference for frontality, shallow space, and large fields. It also prefigures the 1920s interiors where odalisques, screens, and carpets become an interlocking pattern of life. The painting’s lesson—that a social scene can be rendered as an ordered field of color—would echo through later modernists who sought to build worlds with the fewest possible means.

Why the Painting Matters Today

The enduring appeal of “Moroccan Café” lies in its successful translation of hospitality into form. In a time attentive to cross-cultural ethics, the work shows a way to look across difference without overclaiming, to honor another place by attending to its light and cadence rather than by raiding it for exotic detail. It also offers a model for how paintings can act in rooms: not as spectacles but as climate—cooling, clarifying, and quieting the space they inhabit.

Conclusion

“Moroccan Café” is a modestly scaled painting with a vast radius of calm. Figures are reduced to essential shapes; objects are drawn with a few lines; a field of blue becomes shade, air, and social ease. The arch frieze and dotted border bind the scene into an object that behaves like architecture and textile at once. Matisse’s Morocco is not a postcard but a grammar of color and distance that anyone can learn to read. To linger before the painting is to practice that grammar: to follow the rhythm of caps and robes, to feel the pause of the midday room, and to find, in a handful of hues, the quiet dignity of people at rest together.