Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

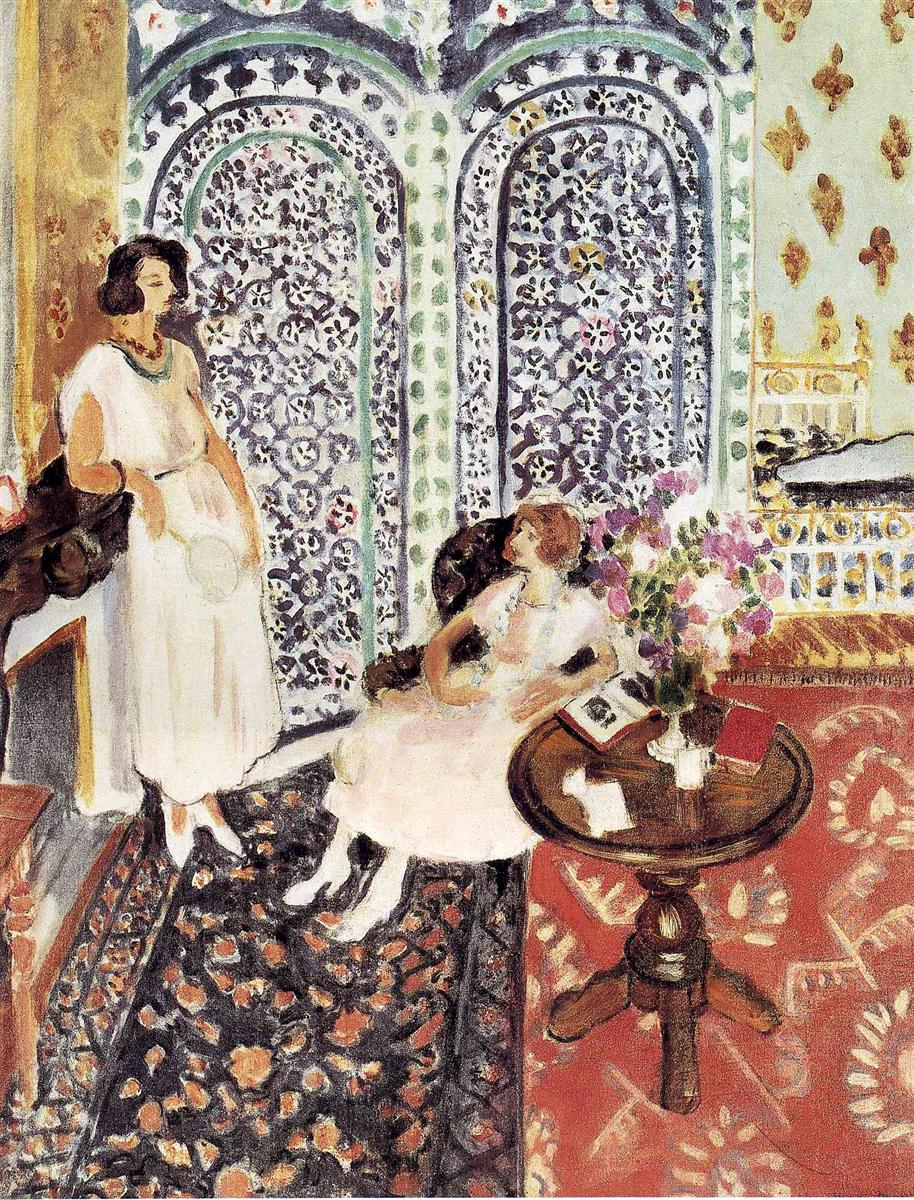

Henri Matisse’s “Moorish Screen” is a chamber of harmonies where figure, furniture, textiles, and architecture converse as equals. The scene is a sun-warmed interior: two women in pale dresses share a quiet interval beside a round wooden table; a vase of flowers blooms at their elbow; patterned carpets meet at a seam; and behind them, an ornate Moorish screen—two arched panels densely braided with vegetal arabesques—rises like a soft, luminous wall. Rather than treating the screen as exotic décor, Matisse makes it a structural instrument that organizes the entire composition. Color, line, and pattern are tuned with such tact that the room becomes a single instrument of poise.

A Nice-Period Interior Scored for Pattern

Painted during Matisse’s Nice years, the work joins his sequence of interiors in which the decorative is not an accessory but the medium of thought. The title foregrounds the screen, yet the painting is not a still life of ornament. It is a living space where people and patterns inhabit the same tempo. The standing woman to the left balances the seated companion to the right; the heavy, dark floral carpet anchors the lower half; a coral-red rug with stylized motifs lifts the right-hand side; and the Moorish screen carries the eye upward in a rain of cobalt, charcoal, and pale mint notes. The result is modern classicism by way of the decorative arts: relationships are clear, rhythms are legible, and the whole feels freshly breathed rather than fussed.

The Moorish Screen as Architectural Music

The screen’s twin arches create a stone-soft architecture that replaces hard walls with lace of paint. Matisse renders the filigree as a field of small, breathing marks—leaf-like and floral—set within repeating lattice. Their density is carefully graded: slightly darker along the inner ribs of each arch, lighter toward the outer margins, so the “wall” holds together without flattening. The vertical stripes of mint dots that flank the arches act like pilasters, tying the screen to the rest of the room and echoing the slender, upright posture of the standing figure. Because the screen is a veil rather than a barrier, it invites the viewer’s gaze to hover without trying to look “through.” In this way, it becomes architectural music—sustained ornament that carries the composition’s main melody.

Figures as Tempos: Standing and Seated

Matisse stages two human tempos. The left-hand figure, upright and attentive, is drawn with long, unbroken contours: the dress falls in a pale column, the arm folds into a relaxed ellipse, the face turns in profile, and a short rope of dark hair anchors the head. The right-hand figure reclines diagonally, knees forward, head tipped back toward the screen—her body echoing the arch’s curve. Each woman’s dress is a different white: the standing figure’s cloth is cooler and flatter; the seated figure’s is warmer, with pearly pinks that gather the red rug nearby. These subtleties keep the figures distinct while holding them within the room’s climate.

Pattern as Timekeeper, Not Distraction

In “Moorish Screen” pattern is never a static wallpaper; it keeps time. The long, dark floral carpet functions like a bass line—steady, weighty, running under the figures. The red rug is more syncopated, dotted with broken leaf and feather motifs that nod toward the screen’s arabesques but in a looser rhythm. The women’s dresses, nearly unpatterned, serve as rests in the score—moments of light where the eye can pause before entering the dense screen again. The bouquet supplies a treble—quick, bright notes of pink, violet, white, and leaf green that sparkle atop the striped tabletop.

Color Climate: Coral, Coal, Cobalt, and Milk

The palette is a four-part chord. Coral red warms the right-hand rug and leaks into the tabletop book and the flowers’ pinks. Coal and charcoal anchor the floral carpet and the darkest vinework within the screen. Cobalt and ultramarine flicker across the screen’s patterning, cooling the interior and recalling Mediterranean air. Milk whites—of dresses, paper, and highlights—knit the figures to furniture and mesh back into the pale mint and ivory of the screen. Tiny accents—emerald necklace, brown tabletop, mustard wall stripe—are placed like punctuation, never shouting over the sentence.

Drawing That Conducts the Eye

Matisse’s line is a conductor’s baton. It thickens where architecture must hold (the table leg, the chair curve, the arch ribs) and thins where light should pass (chin lines, dress edges, flower stems). Facial features are compressed to a few planes and a contour; the point is not likeness but steadiness. The small, dark outline around the seated figure’s calf and shoe pins her to the floor; the more open contour at the standing figure’s shoulders allows her to breathe against the screen. Through these small adjustments the drawing guides the eye’s path while keeping the surface ventilated.

The Round Table as Compositional Hinge

At the right foreground, the round table is both practical and structural. Its circular top repeats the screen’s rounded arches and the standing figure’s arm ellipse. Its dark leg, splayed into three feet, is a visual anchor that prevents the red rug from floating away. On the tabletop, Matisse arranges a small still life—vase, open book, a red-covered volume, slips of paper—whose palette recapitulates the painting’s climate in miniature. The diagonal of the open book points back toward the seated figure’s head, closing a compositional loop.

Light as Relation, Not Spotlight

Illumination in the painting is distributed through value relations. Whites glow differently depending on neighbors: the standing dress appears cooler against the dark carpet; the seated dress warms against the red rug; the papers flare by contrast with the walnut table; the screen breathes because small flecks of raw canvas and pale paint glint among denser strokes. There is no hard cast shadow telling us the hour; rather, the whole room behaves like a well-lit stage, with soft intensity that allows color to carry the mood.

Space Built From Stacked Planes

Depth is achieved without linear perspective. The dark carpet lifts toward us as a tilted plane; the figures occupy a middle band; the screen stands as a patterned wall; and a second pale wall at right, stenciled with ochre motifs, peeks beyond a gilt balustrade. Overlap does the work: the standing woman’s hem interrupts screen and carpet; the tabletop slices into the red rug; the bouquet eclipses part of the balustrade. Because space is built from stacked, legible planes, the viewer can navigate it easily while remaining aware of the painted surface.

A Dialogue With Islamic Ornament

The Moorish screen, with its vegetal arabesques and repeating lattice, alludes to Islamic art’s aniconic tradition, where infinite pattern stands in for the divine. Matisse, who absorbed North African ornament during earlier travels, does not mimic it archaeologically. He translates its logic—the way pattern can be structure—into his own painter’s syntax. The screen stabilizes the room, dictates tempo, and offers a field against which human presence can read calmly. In this sense, the painting is not about “exotic” décor; it is about a Western painter learning from non-Western systems how to make architecture out of pattern and air.

The Ethics of Ease

Matisse famously wanted his art to act like a “good armchair” for the spirit. “Moorish Screen” embodies that ethic without slipping into prettiness. Ease here is not idle luxury; it is the right adjustment among parts. The women are not mannequins but measured presences; the ornaments are not display but structure; the color is generous yet disciplined. The painting proposes a livable equilibrium in which pattern and person, object and air, share a steady pulse.

The Viewer’s Circuit and Renewed Discoveries

The composition invites a repeatable walk. Many viewers begin at the bouquet’s bright cluster, travel across the table to the red book, hop to the seated woman’s face, slide down to the dark carpet, step across to the standing figure’s cool dress, then climb into the Moorish arches where the eye can wander, leaf to leaf, before returning to the flowers. Each lap yields new incidents: a mint dot that keys a column; a coral fleck embedded in the arch; a black leaf on the carpet that rhymes with a vine in the screen; a paper slip that echoes the dress whites. The painting is designed to remain vivid across many viewings.

Sensation Over Description

“Moorish Screen” persuades not by cataloguing furniture or textile weave but by producing the sensation of being in a room where pattern hums like air. The hand remains visible in every passage—the grain of the table, the thick-and-thin drag of a vine, the scumble over the red rug—so the image never congeals into illustration. We believe the space because color temperatures are truthful; we believe the light because values are relational; we accept the people because their postures and proximities are right.

Kinship With the Odalisque Suites—And a Difference

Matisse’s Nice years are often associated with the odalisque theme: reclining models, striped cloths, North African textiles. “Moorish Screen” shares their love of pattern and their basking light, yet differs in tone. Instead of erotic languor, we find domestic composure. The dresses are modern and demure; the gestures are everyday; the still life suggests reading, not display. This emphasis on ordinary leisure—reading beside flowers in a patterned room—makes the painting less fantasy and more proposal: a way to live with artfully tuned surroundings.

Why the Image Endures

The picture lingers because its order feels inevitable: twin arches for the upper field, a long dark carpet for the bass, a red rug for warmth, a round table for hinge, two figures for tempo, a bouquet for treble. Nothing is extraneous; nothing is starved. The painting gives you a steady scaffold of pattern and then invites you to enjoy how color and touch animate it. That synthesis—structure plus breath—is the reason the work continues to feel fresh.

Conclusion

“Moorish Screen” is Matisse’s demonstration that the decorative can carry serious form. He composes a lucid interior where pattern is architecture, figures are rhythms, and color is climate. The Moorish arches breathe rather than wall off; the carpets keep time; the table knots the room; and the women lend it humane tempo. In this room, ornament is not an extra—it is the means by which calm is made visible. The painting asks the viewer to inhabit that calm, to feel how relations tuned with care can turn ordinary furnishings into a symphony of ease.