Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

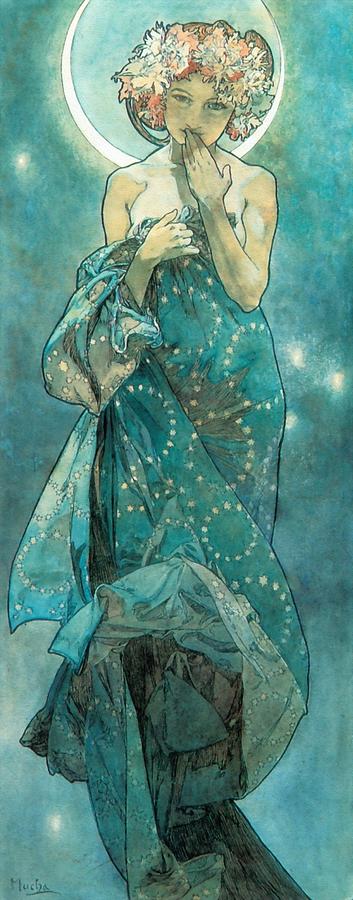

Alphonse Mucha’s “Moonlight” is one of those images that seems to arrive already glowing. A lone figure, crowned with flowers and haloed by a crescent, floats on a column of night. She gathers a star-pricked shawl around her body and listens to the silence with a finger poised at her lips. The narrow, vertical panel amplifies her ascent as folds of turquoise cloth unfurl like tides. It is a nocturne about attention and shelter, a manifesto for Art Nouveau’s belief that line, color, and ornament can make the invisible palpable. Where other moon goddesses dominate the sky, Mucha’s “Moonlight” invites the viewer into a private weather where thought brightens slowly, like eyes adjusting to darkness.

Historical Moment

The work belongs to the rich seam of lunar images that Mucha made around the turn of the twentieth century, when Paris was his adopted studio and the city’s appetite for decorative panels, calendars, and lithographic suites seemed inexhaustible. He had already reshaped poster art with his arabesque heroines, and he was sharpening the symbolic vocabulary that would later support his grand national canvases. “Moonlight” is part of that development: a transitional piece that keeps the commercial clarity of his posters while yielding to the contemplative hush of his later allegories. Its elongated format, unbroken by textual borders, shows an artist taking full advantage of the decorative panel as a stage for myth distilled into everyday beauty.

Subject And Iconography

Mucha’s subject is a woman who is also the night. The crescent describes both moon and halo; the wreath of pale blossoms reads as a coronet of dew; the shawl is a firmament of tiny stars. Rather than point to the heavens, she shelters herself in them. The gesture at her lips is not coyness. It is a call to quiet, a reminder that moonlight is the hour when inwardness clarifies. The figure is neither goddess nor saint in any strict doctrinal sense; she is an allegory—a human vessel that lets the lunar world take on posture and temperament. In this, Mucha is a child of Symbolism: meaning arrives by suggestion, and the viewer is trusted to complete the circuit.

Composition And Format

The panel’s architecture is deceptively simple. A tall rectangle contains one figure who nearly fills the vertical; she is anchored near the bottom by a dark, weighty hem and crowned near the top by the crescent’s cool ring. Between those poles the body describes an elegant S-curve. The leftward drift of the shawl and the rightward turn of the knees generate a counterpoint that keeps the composition alive. There are no hard borders, only the night itself, mottled with soft, nebular lights. The figure’s feet do not step on ground; they dissolve into dusk, a choice that renders her both present and unmoored. The result is a choreography of suspension—what music would call a sustained note.

The Crescent As Moral Geometry

Mucha’s crescents act like compasses. Here the pale arc fixes the figure in the firmament, framing the head and flowers while opening a small sphere of coolness around the brow and eyes. It is a device with a long art-historical pedigree—moon, aureole, arch—and Mucha exploits all three at once. The crescent is cosmic emblem, spiritual sign, and compositional anchor. Its crisp contour also sharpens our attention to the soft complexity of hair and blossoms that it encloses, a contrast that becomes a visual metaphor for clarity surrounding thought.

Gesture And Psychology

The right hand rises toward the mouth, the index finger barely touching the lower lip. The left hand gathers the shawl close. These are not mannered poses but psychological cues. The first invites silence, the second offers protection. Together they say: keep still, keep warm. This quiet authority is typical of Mucha’s allegorical women. They seldom command; they persuade by presence. Here the face is direct and unmasked—no jewelry beyond the floral crown—so the viewer can meet a person rather than a mannequin of myth.

Drapery As Language

Few artists make cloth speak as fluently as Mucha. In “Moonlight” the shawl is a whole night sky held at human scale. Its weighty lower folds secure the figure in the panel the way a bass line secures melody; its upper planes catch milky glints that read as moonbeams; its floating edges produce the sensation of breeze that a stage manager might dream about. Stars are distributed like embroidered beads: densest where the cloth turns toward us, sparser where shadow thickens. In the absence of architectural setting, drapery becomes the room, and the room is the night itself.

The Color Of Night

The palette rests on a family of blue-greens that collectors sometimes call “Mucha blue”—a mineral, seawashed hue that can feel at once luxurious and cool. Into that field he introduces secondary notes: the peach tones of skin and blossoms, a graphite-like gray in the deepest creases, a dusting of white starlight. The dominance of turquoise is crucial. It refuses the purple melodrama of many nocturnes and chooses instead a color with daylight memory in it, as if the moon were reminding us of the sea. The harmony is gentle, never sugary, and the small warm accents keep the blues from turning anesthetic.

Light As Breath

There is no single spotlight. Illumination seems to exist as a climate—everywhere and nowhere—more like breath on skin than like stage light. The crescent glows but does not cast harsh shadows; the stars flicker but do not dazzle. Mucha distributes small highlights along the shawl’s ridges and the cheek’s roundness, enough to model form but not enough to break the dream. This evenness of light encourages a kind of democratic looking: we dwell as easily on a hem’s turn as on the face, and so the image reads as an ecosystem rather than as a hierarchy of details.

Line, Wash, And Surface

Under the glazing and thin color rests the confident line of an illustrator. Contour stays supple—thicker where form needs authority, finer where air should pass. Within those boundaries, translucent washes build the atmosphere, their tide lines barely visible at the edges of larger passages. The technique matters because the medium becomes metaphor. Watercolor and gouache behave like moonlight: they layer without shouting, they let paper glow through, they reward the second glance. Mucha’s lithographs often translated these painterly solutions into print; here we enjoy them at their most immediate.

Comparison With Sister Images

Mucha painted and printed several lunar personifications—the 1902 “The Moon,” the quartet “The Moon and the Stars,” and variants often titled “Clair de Lune.” “Moonlight” is kin to those but more inward. Many earlier versions stage the figure against a patterned border with ornamental devices that announce their decorative purpose. This panel relaxes the frame and lets the night occupy the edges. The gesture is subtler too. Where other moons offer goblets, tap stars, or spread arms to the sky, this one guards the quiet. It is the difference between pageant and soliloquy.

Art Nouveau Without A Cage

A hallmark of Art Nouveau is the transformation of natural forms into pattern—arabesque foliage, enamel-like fields, whiplash lines. “Moonlight” preserves that grammar without enclosing it in a hard frame. The shawl’s dotted stars and flowered wreath supply the ornamental vocabulary; the figure’s contour provides the whiplash; the long format becomes an architectural element. But there is no tiled border, no emphatic cartouche. The style breathes. It is Art Nouveau turned to meditation rather than commerce.

The Body And The Ethics Of Modesty

Mucha’s women are famously present and yet unexposed. Here the shawl’s sweep hints at curves without parading them; the bare shoulders read as human, not provocative. The effect is respect rather than prudery. He was not painting a body to be consumed; he was shaping a person to host an idea. In “Moonlight,” that idea is sanctuary—how we keep the night from frightening us, how we keep our minds from scattering. The figure’s modesty becomes the portrait of a discipline.

Movement And Rhythm

Imagining the panel as music clarifies its charm. The lower hem supplies the low notes, heavy and slow. The midsection provides a string of triplets—the fluttering scarf ends and tiered underskirt. The upper half settles into a sustained, high tone—the face and hands held in stillness. The whole page plays as a nocturne: simple melody, patient accompaniment, no sudden crescendos. Even the small bright stars read like dotted notes that keep time across the bar lines.

How The Eye Travels

Mucha designs the viewer’s path with care. We begin at the crescent, slide into the flowers, meet the face, and pause at the finger’s whisper. From there the eye descends through the starred shawl, catches on the bright corner where fabric turns, and drops to the darker weight below. The composition then lifts us back along the leftward sweep of cloth to the edge of the page, where the night reclaims us. Every return to the face feels earned. The artist has taught us how to look without our noticing.

Folklore And Humanism

The flower crown reads as a soft Slavic echo, a reminder that Mucha’s ideal women often carry memories of village festivals and midsummer rites. Yet the painting remains comfortably cosmopolitan. There is no ethnographic costume, no insistence on national motif. The marriage of folk tenderness and urban polish is central to the artist’s humanism: archetypes are only useful if they remain hospitable to many viewers. “Moonlight” keeps its mythology generous.

Decorative Purpose And Everyday Use

Panels like this were designed to live with people—in salons, bedrooms, studies—rather than in museums alone. Mucha understood that art hung at home must be legible at a glance and comforting at length. “Moonlight” satisfies both demands. Seen across a room, it compresses into a single glyph: crescent, figure, turquoise column. Studied up close, it dilates into fabrics, freckles of light, and the small drama of gesture. It is not an illustration of a story; it is a companion to hours.

Technique As Hospitality

The edges of washes, the granulation of pigment, and the tactful line all contribute to the work’s hospitality. Nothing is over-finished. Paper shows through like breath; small irregularities keep the surface human. Mucha’s graphic intelligence never hardens into mechanical sheen. The best decorative art knows when to stop. It leaves room for the viewer’s eye to complete a fold or supply the shimmer of a star. “Moonlight” embodies that tact.

Legacy And Contemporary Relevance

More than a century later, the image feels freshly useful. In a culture saturated with glare, it praises low light. In a world of constant speech, it models a fingertip’s call to quiet. Its beauty is not an escape from modern life but a practice for living inside it—the practice of drawing a shawl of attention around the self so that thought can form. Designers still borrow its color; photographers still quote its pose; viewers still feel steadier after standing in its weather. That constancy is the real fame of Mucha’s art.

Conclusion

“Moonlight” distills Alphonse Mucha’s gifts—supple line, lucid composition, humane allegory—into a single, vertical hush. It offers a vision of night that does not threaten but keeps, a person who does not perform but attends, a style that does not imprison but opens. The crescent is an emblem of cycles; this painting honors that truth by meeting us reliably in many seasons of life. Each time, the shawl falls a little differently and the stars seem newly placed, but the invitation remains the same: be still, gather the sky, and let your eyes learn to see in the dark.