Image source: wikiart.org

First Impressions: A Road That Breathes and Trees That Lean

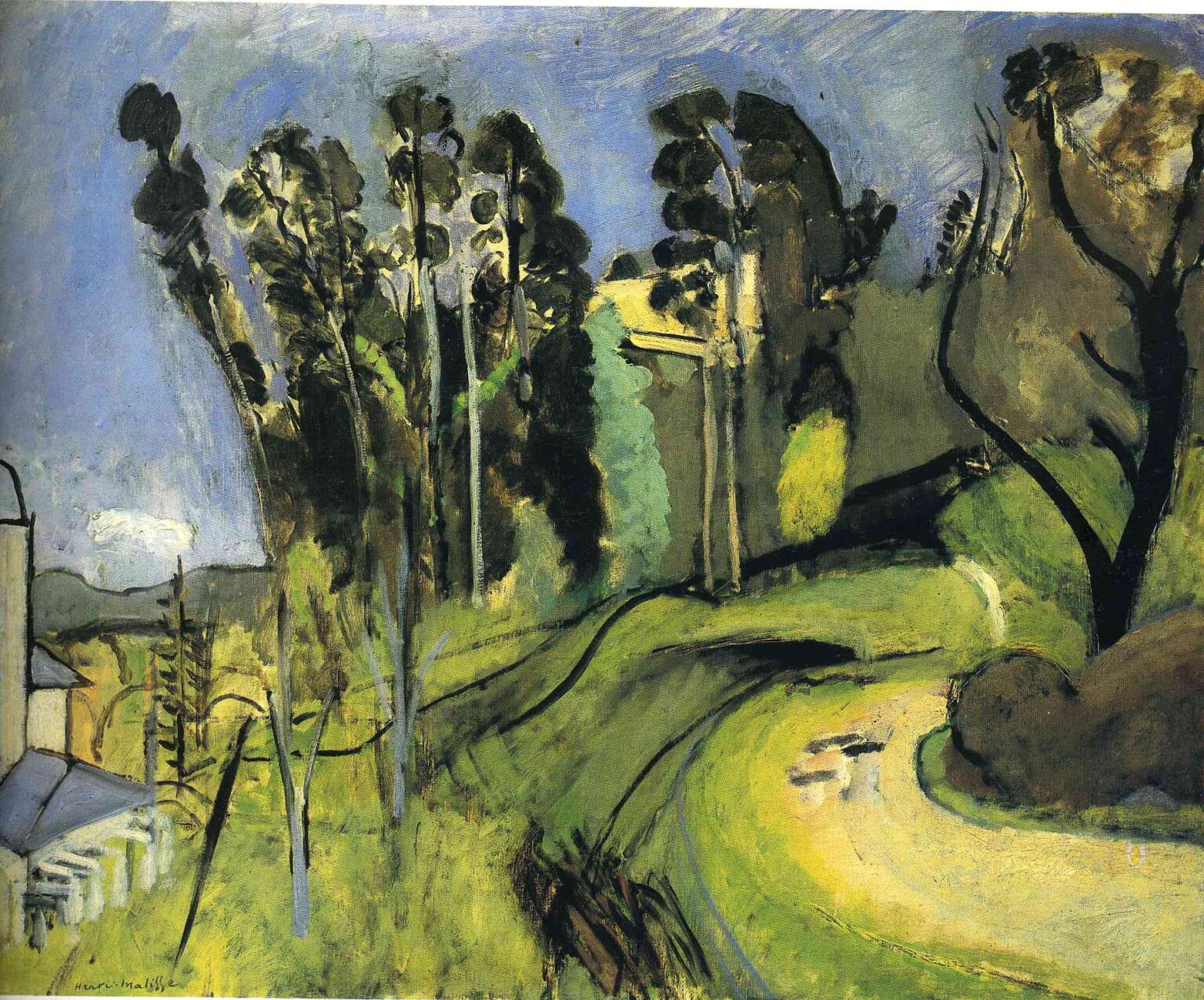

Henri Matisse’s “Montalban, Landscape” from 1918 greets the eye with a sweeping, pale road that curves like a crescent through a hillside and disappears behind a mass of foliage. Tall, wind-leaning trees launch into a blue, quick-brushed sky; black calligraphic trunks and limbs snap like ink across planes of green; and, at left, angled rooflines and a pale wall hint at the outskirts of a town. Nothing feels fussy. The image is built from large, decisive relations—curve against vertical, light against dark, warm against cool—so that the landscape reads at once and then deepens during slow looking.

1918 and the New Key of the South

The date matters. In 1918 Matisse consolidated a new grammar forged on the Côte d’Azur: tuned color rather than shock, shallow but convincing space, visible brushwork, and black treated as a positive color. “Montalban, Landscape” stages that grammar outdoors. The canvas preserves the decisiveness of his mid-1910s drawing while tempering it with Mediterranean air. He rejects theatrical contrasts for measured temperature shifts and replaces descriptive detail with rhythmic structure. The result is an image that is at once modern and classical—restful in its order, alive in its surface.

Composition: Crescent, Ladder, and Brackets

The design turns on three big moves. First is the bright road, a crescent that begins in the lower right and arcs toward the middle distance. It both organizes the ground and invites the viewer inward. Second is a ladder of verticals: trunks rise in a cluster at center-left, echoed by a single arcing tree at the right edge. These uprights stabilize the picture and counter the road’s sweep. Third are bracket shapes—the dark mound at lower right, the roofline and walls at lower left—that hold the composition laterally so the eye does not slide out of frame. Together, these forces—curve, ladder, brackets—give the scene its legibility and momentum.

The Road as a Visual Sentence

Matisse’s road is not literal topography; it is a sentence that the eye reads. Its pale surface pulls light into the painting, its edges describe the hill’s pitch, and its narrowing width regulates depth without perspective tricks. Around the road, darker grasses and bands of green bank like riversides, quickened here and there with short strokes that suggest raked earth or wind-tossed blades. A few small, cool notes flash inside the road—wet spots or reflected sky—proving how little information is required to conjure experience.

Trees as Calligraphy and Architecture

The trees are not botanical records; they are calligraphic structures. Trunks are laid in with long, elastic strokes that thicken and thin with the brush’s pressure. Crowns are masses made from clustered, rounded daubs that catch light and then collapse into near-black shadow. Near the center, several trees step diagonally up the hill; their vertical cadence creates a scaffolding that holds the middle ground like a colonnade. At far right, a single, serpentine trunk arcs across the sky, answering the road’s curve and keeping the picture from tilting left.

Palette: Tempered Greens, Blue Air, and Living Darks

Color is tuned rather than saturated. Greens range from lemon and sap to olive and bottle, organized so that cooler notes recede and warmer notes lift. The sky is a quick, airy blue—thinly brushed so lighter streaks read as cirrus and the weave of the support shines through. Darks are near-black but warm and cool by adjacency: cooler when pressed against sky, warmer where they sink into grass. Patches of pale yellow-green and a minty vertical strip in the center suggest sunlit shrubs or a cut through trees, placing a high note where the eye needs rest. Because Matisse avoids theatrical saturation, temperature carries the emotion of place.

Black as a Positive Color, Not a Void

Matisse’s darks act like pigments, not holes. He uses them to draw trunks, to state the deepest pockets of foliage, to score edges along the road, and to hinge rooflines to walls. The black lifts and cools next to blue, warms and glows near the yellow road, and intensifies neighbor greens by contrast. That positive use of black is crucial to the painting’s architecture: it anchors the airy palette and supplies the bass line to the landscape’s chord.

Light as Climate Rather Than Spotlight

There is no single, theatrical light source. Instead, light arrives as climate. The road is brightest where it turns toward us, grass warms where slopes face the implied sun, and halftones cool in the underwood. Planes turn by temperature rather than heavy chiaroscuro—cooler blues and grays under canopies, warmer greens on open ground—so the landscape breathes. This approach captures a day rather than a moment: you can almost feel the air moving across the hill.

Brushwork: The Pace of Making Left Visible

The painting wears its making without apology. The sky’s strokes are broad and diagonal, leaving ridges that catch light; the trees’ crowns are packed with small, rounded touches; trunks sweep in single gestures; grass is scumbled and dragged over under-color to create nap. The road gathers thin, creamy passes whose edges overlap in faint halos, as wet paint met wet paint. Each zone keeps its tempo—sky slow, trees pulsing, road gliding, grasses quick—so that the surface itself becomes a record of time and weather.

Edges and Joins: Where Forms Share Air

Edges are tailored with care. Where foliage meets the sky, boundaries alternate between crisp and feathered, imitating leaves dissolving into light. Where the road cuts into grass, a dark, narrow seam seats it; where hill meets distance, the join softens so atmosphere can intervene. Along the left edge, roofs and a pale wall meet vegetation with a firm line—architectural clarity against organic drift. These varied joins prevent the simplified shapes from looking pasted on and create the illusion of shared air across the scene.

The Architectural Margin at Left

That small, stepped sequence of roofs and wall at lower left is strategic. It introduces human measure, calibrates scale for the trees, and adds a moment of angular geometry to a composition dominated by curves. Its pale planes echo the light of the road and tilt us subtly into the picture. It is also an index of place: Montalban (often written Mont Alban in Nice) is a hill crowned by fortifications and villas; those cool roofs and pale walls are believable fragments of that built world, glimpsed as you round a bend.

Depth Kept Close to the Plane

Matisse refuses deep perspective corridors. Depth is achieved through overlap (road before mound, mound before trees, trees before sky), through value steps (foreground lights brighter than distance), and through temperature (cooler blues and grays toward the horizon). Because space is kept near the plane, the picture reads with one glance as a designed arrangement of shapes even as it convinces as a place you could walk into. That balance—surface clarity with spatial believability—is a hallmark of his mature landscapes.

Rhythm: Scallops, Serpents, and the Slow S

The painting’s music unfolds in three families of rhythm. Scalloped edges of canopies repeat across the skyline; serpentine trunks bend and counterbend in a slow dance; the road lays down a long S-curve that guides the eye. The hill’s contour lines echo this S with fainter strokes. As you read the scene from right to left and back again, those rhythms interlock and carry you forward. The painting never stands still, but its movement is measured rather than agitated.

Weather and Time of Day

Hints of weather emerge from color and stroke. The sky’s cool blue leans toward afternoon; low, pale cloud shapes drift at left; the road’s warm light suggests late sun catching dust; the shadows pooled beneath crowns indicate air clear enough to carve forms without turning them into silhouette. It feels like a breezy day after rain—clean light, moving air, the scent of wet leaves and sun on stone.

A Conversation with Cézanne and the Fauves

The lineage is clear but rephrased. From Cézanne: the construction of volume by adjacent planes and temperature shifts, not by theatrical shadow; the sense that a hill is a stack of tilting planes. From Fauvism: the courage to let color and line carry emotion. But Matisse avoids both Cézanne’s faceting rigor and his own earlier fireworks. Here he composes for calm: a limited chord, a few black anchors, and a disciplined surface where each relation is necessary.

Relation to Sister Works of 1918

Seen alongside “Landscape around Nice,” “Landscape with Olive Trees,” or “The Road,” this canvas takes a bolder linear stance. The calligraphic blacks are more declarative; the road has greater agency as a design element; the sky is brushed with visible diagonals rather than feathered veils. Compared with “Large Landscape with Trees,” the present work is more animated, its tree forms more individuated. Compared with “The Stream,” it is sunnier and more architectural, thanks to that left-hand margin of roof and wall. As a group, these works map Matisse’s outdoor grammar in 1918: rhythm before detail, temperature before chiaroscuro, and black as architecture.

Guided Close Looking: A Walk Through the Picture

Enter at the bright road in the lower right and feel the creamy paint catch on the canvas tooth. Track the thin dark line along its inner edge—it’s the seam that sets the road into the hill. Move toward the small reflective flecks mid-curve; let them bounce you upward into the dark mound. Climb the serpentine trunk at far right and cross the skyline along scalloped crowns that step leftward. Drop down into the central ladder of trunks; notice how each leans at a slightly different angle, like a conversation in wind. Slip toward the minty green vertical—perhaps a cypress or a cut of air—and then descend the hill into rooflines and the pale wall. Finally, skim the blue sky’s diagonal striations back to the road. Each circuit clarifies the painting’s inner pulse.

Material Evidence and the Courage to Stop

Look for pentimenti—adjustments left visible. A trunk widened with a second pass of dark; a canopy edge restated to interrupt too-smooth a curve; a patch of sky reclaimed between leaves; the road’s boundary repainted to sharpen the turn. Matisse does not polish these decisions away. He halts when relations feel inevitable, not when the surface is cosmetically uniform. That earned inevitability gives the landscape its quiet authority.

Lessons Embedded in the Canvas

For painters and designers, “Montalban, Landscape” functions as a patient tutorial. Use black as a living color to anchor airy chords. Model with temperature shifts rather than heavy shadow. Let a few big shapes—the S of the road, the ladder of trees—carry the narrative of looking. Vary edge quality to seat forms in shared air. Keep depth near the plane so the image reads instantly and then rewards sustained attention. Above all, trust rhythm—curve against vertical, warm against cool—to deliver feeling more directly than detail.

Why the Painting Still Feels Contemporary

A century later, the canvas looks fresh because it matches contemporary habits of seeing. Large shapes read at a glance; the palette is sophisticated rather than loud; the process is legible and honest; and space is shallow enough to sit comfortably next to photography and graphic design. The road’s S-curve could be a logo stroke; the tree calligraphy could be vector lines; the tuned greens and black anchors would not look out of place in a modern interface. Yet the painting remains resolutely human—about breath, daylight, and the pleasure of moving through trees toward an opening.

Conclusion: A Hill Built from Essentials

“Montalban, Landscape” distills a walk along a Mediterranean hillside into a few necessary relations: a road of light, a ladder of trees, an airy sky, measured greens, and positive blacks. With those means Matisse constructs depth without strain, atmosphere without theatrics, and rhythm without noise. The painting is generous to live with because it is disciplined: nothing redundant, nothing missing. It offers the restorative calm of order discovered outdoors—a road that breathes, trees that lean, and blue air you can almost step into.