Image source: artvee.com

Introduction to the Painting

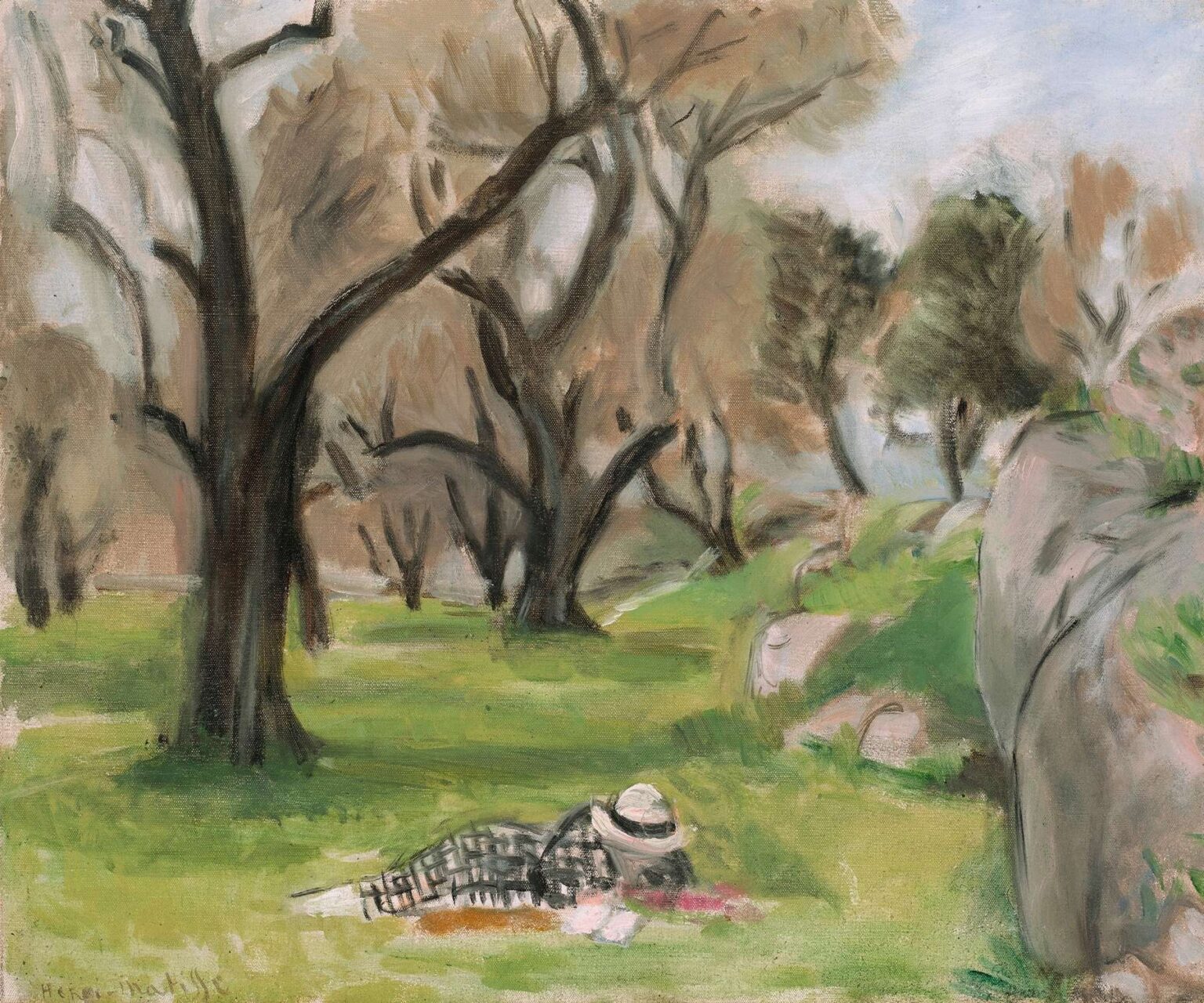

“Midi Landscape” places us in a sun-washed grove where dark trunks arc like calligraphy across quick patches of spring green. A single figure lies stretched on the grass near the foreground, hat tipped, clothes patterned in checks that echo the broken shadows around her. To the right, rounded rocks climb a low rise; to the left, trees mass into a screen of trunks and branches; above, a pale sky slips through a gauze of foliage. The scene is simple, yet every element participates in a larger rhythm of curve, counter-curve, and quiet intervals. Henri Matisse, working in 1923 at the heart of his Nice period, turns a modest corner of the Midi into an image of composure powered by line.

The Title and the Spirit of the Midi

The word “Midi” in French names both the south of the country and the midday hour. Matisse’s canvas carries both meanings. The southern light is unmistakable: cool and clear, it clarifies forms without casting theatrical shadows. The hour feels like noon or early afternoon, when the ground’s greens are brightest and the sky whitens slightly at the horizon. Rather than describe a particular landmark, the painting offers a distilled sensation of the region—olive-toned foliage, chalky stones, air that makes edges read cleanly—so the title becomes a statement of climate and tempo as much as geography.

Nice Period Context and the Pursuit of Calm

By 1923 Matisse had settled into a routine of measured work in Nice, alternating between intimate interiors and nearby landscapes. After the disruptions of war and the exploratory strictness of the late 1910s, he sought a language of clarity and rest. “Midi Landscape” belongs squarely to this project. It borrows the Nice interiors’ emphasis on a few tuned colors and strong linear scaffolding, then carries those values outdoors. The aim is not optic shock but a sustained chord in which every mark is necessary.

Composition as Choreography

The painting’s design can be read as a choreography of arcs anchored by a diagonal rise. A dark trunk springs from the lower center and sweeps left; another counters it to the right; secondary branches repeat the movement at smaller scales. The ground plane climbs gently toward the right, where boulders pile up like pauses in the rhythm. The figure lies exactly where the main trunk’s curve meets the edge of the grassy rise, so our eye continuously loops from the body to the trees, from repose to motion and back. The composition is stable without being static because the big curves keep the surface elastic.

The Figure as Scale, Accent, and Theme

Matisse reduces the reclining figure to a handful of essentials: the ellipse of a hat, a pinkish face turned down, the patterned rectangle of a dress or coat, and a pale strip of leg. She functions first as a scale unit, confirming the trees’ breadth and the meadow’s openness. She is also an accent of value and pattern, a compact cluster of darks and lights within a field of moderated tones. Most importantly, she introduces the theme of rest. Her pose is a visual rhyme to the painting’s larger restfulness—color held in a narrow key, line allowed to flow—so that human ease and environmental calm reinforce one another.

Color Key and Tonal Economy

The palette is disciplined: olive and citron greens laid thinly over the ground, gray-brown trunks deepened with black, a skim of whitish blue in the sky, and hushed pinks and violets tucked into rock and foliage. The greens do the heavy lifting; they are modulated rather than multiplied, shifting temperature to indicate light without breaking harmony. Black is used constructively, not to deaden but to quicken adjacent hues, and it provides the calligraphic bite that holds the composition together. Because the key is so restrained, small departures—a streak of warm pink near the figure, a cool bluish wash in distant trees—read like musical ornament, sharpening attention without upsetting balance.

Light and Atmosphere

Light in this canvas is a condition rather than an event. Edges soften as they move away from us; trunks darken where they meet foliage and lighten as they pass in front of the sky; the rocks carry a thin, milky glare that suggests chalk warmed by noon sun. Matisse resists cast shadows that would pin the scene to a specific second; instead he constructs volume through gentle value steps and subtle temperature shifts. The air feels dry and lucid, typical of the Riviera, and it gives every contour a natural clarity.

Drawing with the Brush

The picture’s decisive strength is its drawing. Matisse paints as if writing, laying down elastic lines that thicken and fade according to pressure. The major trunks are single gestures; branches break and resume like clauses; leaf masses are suggested by quick, rounded strokes that act more as verbs than as nouns. He rarely resorts to outline for its own sake. Where a boundary is needed—trunk against sky, rock against grass—he lets two color fields meet to make the edge. This drawing by adjacency maintains atmosphere while keeping forms legible.

Surface, Touch, and the Evidence of Making

The paint is thin in many passages, allowing the weave of the canvas to show. This decision suits the subject: the thinness reads as air. In the trees and rocks he increases the load slightly, letting soft ridges of pigment catch the light. A few visible corrections—ghosts of earlier strokes, a trunk shifted, a rock re-shaped—remain on the surface and make the picture feel present tense. The viewer senses the time of the painter’s hand, a quality Matisse prized because it keeps the image lively without resorting to noise.

Space Without Theatrics

Depth is organized by overlap and by the progressive cooling and lightening of color, not by hard perspective. The nearest trunks carry the darkest darks; the middle grove softens into gray-greens; beyond, a distant bank of trees and a light sky close the space. The right-hand boulders step back in gentle terraces. This shallow staging preserves the primacy of the surface while still conveying a believable place. The viewer experiences the grove both as pattern and as terrain.

Rocks as Counter-Rhythm

The boulders to the right are more than local detail. Their rounded volumes provide a counter-rhythm to the trees’ arabesques. Where branches whisk, rocks sit; where trunks leap, rocks lodge. Their pale surfaces catch the field’s light and reflect it back as cooler notes, making a quiet dialogue with the warmer greens. They also carry the path visually into depth: small arcs and slashes of paint near their bases imply a worn track that the eye follows upward.

Editing and the Power of Omission

Matisse leaves out everything that would not serve the painting’s order. There are no blossoms, no dappled leaf shapes, no texture for texture’s sake. The sky is a single breathing field; the ground is a handful of tones; the figure’s features are not described. This editing is not austerity but concentration. By pruning description, he allows relations—curve to curve, warm to cool, dark to light—to carry meaning. The omissions ask the viewer’s imagination to complete what is deliberately only suggested, which deepens the sense of participation.

Movement and the Viewer’s Path

The composition guides the eye as surely as a path guides a walker. We enter along the bright grass at lower right, pass the resting figure, and are lifted by the big left-leaning trunk toward the canopy. From there we drift across the screen of trees and descend along the rocks’ slope back to the meadow. The loop is unhurried; it keeps us within the picture’s calm weather. That circular movement echoes the figure’s rest—no destination, only looking.

Relation to the Nice Interiors

Though an outdoor scene, “Midi Landscape” speaks the same language as Matisse’s Nice interiors of the early 1920s. In those rooms, shutters, screens, and patterned draperies become large, tuned fields held by strong linear armatures; figures rest within a decorative order that never feels mechanical. Here, the grove functions like an interior: the trunks are the armature; the leaf masses are patterned fields; the reclining body is a guest within a harmonized space. Seeing the continuity clarifies the period’s ambition: to construct environments of poise—outside or inside—by aligning a few essential shapes and a restrained palette.

Constructive Black and the Calligraphic Tradition

Few modern painters use black with Matisse’s confidence. In this canvas the black is supple and melodic. It articulates joints in the trees, threads through the figure’s plaid, and sets the rocks into relief without deadening the greens nearby. The effect owes something to the calligraphic tradition—ink used not merely to outline but to energize a surface. Because the black has its own life, color can remain light and thin; the line carries structure while color supplies air and temperature.

Emotional Register: Composure with a Pulse

The painting’s tone is composed, even meditative, but not inert. The figure’s ease, the measured key, and the open air all speak of recovery and quiet after years of turmoil in Europe. Yet the long, swinging lines keep energy stored in the scene, like wind passing invisibly through boughs. This balance—calm held by movement—captures what many viewers cherish in Matisse’s Nice period: serenity that arrives by design, not by absence.

Comparisons and Kinships

Placed beside the Maintenon riverbank pictures of 1918, “Midi Landscape” is brighter in key and more open in structure; placed beside the odalisque interiors of 1923, it trades ornamented fabric for the natural décor of trees and rocks while keeping the same harmonic rigor. It also nods to earlier park scenes, such as the Luxembourg Gardens views of 1902, where color already began to behave as architecture. Across these works a method emerges: start with a simple motif, limit the palette to a tuned chord, draw with the brush in decisive arabesques, and place a body—or a path or a rock—where the rhythms meet.

Material Presence and Scale

While the scene expands outward, the painting remains intimate in its facture. The scale of marks matches the size of forms: large trunks in single sweeps, mid-sized leaf clusters in clusters of strokes, ground laid in broader, transparent passes. The uniformity of touch across figure, rock, and tree keeps the world knitted together. From across a room the painting reads as a stable pattern; up close it offers the pleasure of brush ridges, thin scrapes, and the small surprises of color meeting color.

Modernity As Clarity

“Midi Landscape” is modern without aggression. It refuses anecdotal detail in favor of essential relations; it lets the surface declare itself as painted while preserving the recognizability of place; it constructs an experience of rest through design rather than sentiment. This clarity—neither schematic nor showy—explains why paintings from the Nice years continue to feel fresh. They meet the eye quickly, then reward lingering with quiet intricacy.

Conclusion: A Grove Tuned to Rest

In this canvas Matisse composes a grove like a piece of chamber music. The large trunk writes the main phrase; secondary branches answer; rocks provide soft percussion; the figure supplies a sustained note of repose. Greens are tuned to one another; black sings through them; sky and ground share the same calm light. Nothing in it is excessive; everything is considered. “Midi Landscape” holds a small world in balance and, by doing so, models the larger promise of painting at this moment in Matisse’s career: that harmony, carefully constructed, can feel as natural as air.