Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

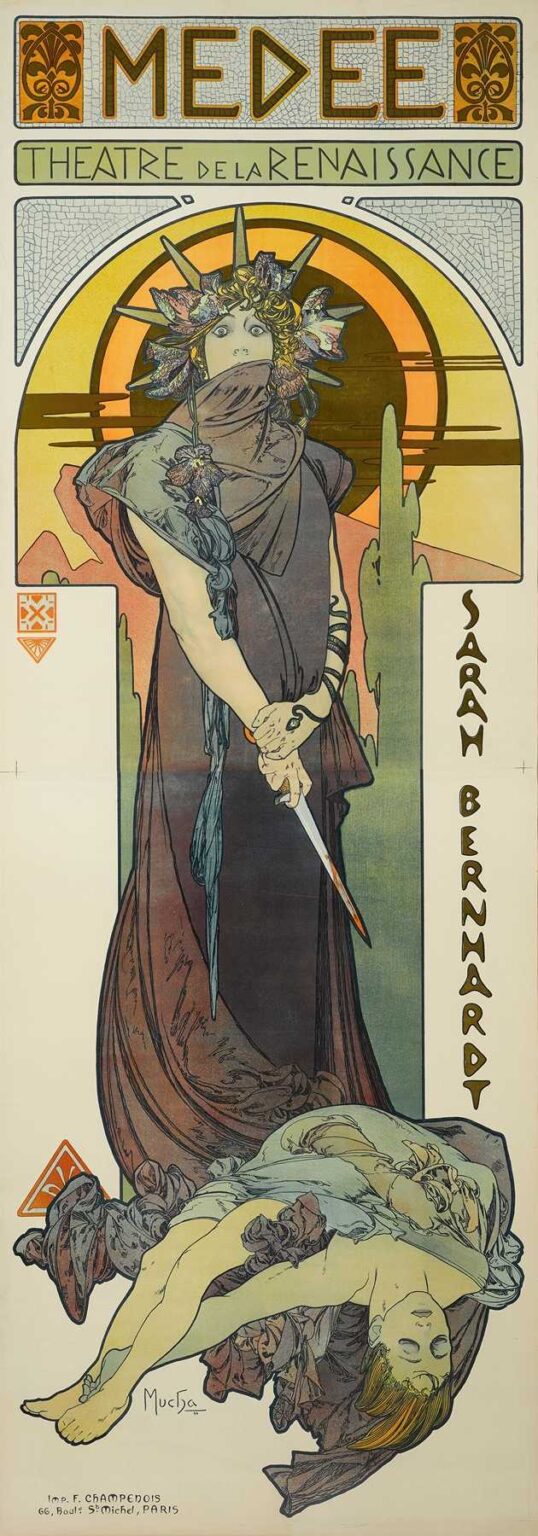

In 1898, Alphonse Mucha created the striking lithographic poster Médée to promote Sarah Bernhardt’s performance in Euripides’ classic tragedy at the Théâtre de la Renaissance. Measuring nearly 120 by 50 centimeters, this work exemplifies Mucha’s mature Art Nouveau style—melding sinuous lines, decorative motifs, and mythological drama into a unified visual statement. More than a simple advertisement, Médée captures the psychological intensity of the play’s vengeful heroine, while showcasing Mucha’s mastery of composition, color, and typographic integration. This analysis explores the poster’s historical context, artistic innovation, mythic symbolism, technical execution, and enduring influence on graphic design.

Historical and Theatrical Context

The late 19th century was a golden age for French theatre, with Sarah Bernhardt (1844–1923) reigning as Europe’s most celebrated actress. Her passion for classical drama led her to stage Médée—adapted by Maurice de Guérin from Euripides—in December 1898 at the Théâtre de la Renaissance. Parisian audiences flocked to see Bernhardt embody the sorceress who murders her children to punish unfaithful Jason. Meanwhile, poster art had become a vital promotional tool, with Paris’s boulevards plastered in vibrant lithographs. In this competitive environment, Mucha was Bernhardt’s go-to artist, having designed her breakthrough Gismonda poster in 1894. The Médée sheet thus arrived at the nexus of theatrical spectacle, celebrity culture, and the decorative revolution known as Art Nouveau.

Alphonse Mucha’s Career and Art Nouveau

By 1898, Alphonse Mucha had fully crystallized his signature aesthetic: elongated female figures, organic whiplash curves, ornate halos of botanical ornament, and integrated custom lettering. After migrating from his native Moravia to Paris in 1887 and a formative period in Munich, Mucha found fame through Bernhardt’s patronage. His 1894 poster for Gismonda sparked the “Mucha style,” making him the most sought-after poster artist of the Belle Époque. Over the next four years, Mucha refined his lithographic technique—layering translucent inks, experimenting with metallic highlights, and balancing natural forms with geometric patterns. The Médée poster represents a mature phase: it channels the artist’s decorative exuberance into a darker, more dramatic narrative.

Commission and Promotional Purpose

Théâtre de la Renaissance aimed to attract discerning theatre-goers with Bernhardt’s star power and the ancient allure of the Médée myth. Mucha’s commission was to produce a poster that would simultaneously announce dates, convey the play’s tragic intensity, and align with the Art Nouveau ethos of beauty in everyday life. Rather than depict a scene verbatim, Mucha chose to evoke the play’s mood through emblematic imagery: a startled, veiled figure holding a blood-tipped dagger, poised above her fallen children. The poster’s public placement—on kiosks, station walls, and café windows—ensured maximum exposure, while attracting both theatregoers and art enthusiasts to the Renaissance’s repertoire.

Mythological Background of Médée

Médée (Medea) is one of Greek drama’s most complex heroines. A sorceress and princess of Colchis, she aids Jason in obtaining the Golden Fleece, then marries him. When Jason abandons her for political gain, Médée exacts vengeance by murdering their children and Jason’s new bride. Euripides’ 431 BCE play explores themes of passion, betrayal, and the limits of human agency. Mucha’s poster distills this rich narrative into a single, haunting moment: the instant before vengeance is fully realized. The work’s mythic underpinnings resonate with Art Nouveau’s fascination with ancient symbolism, positioning Médée as both timeless and terrifying.

Composition and Spatial Design

Mucha arranges Médée on his characteristic vertical format, optimizing it for street poster display. The composition divides into three registers:

Title Panel: The top third bears the bold word “MÉDÉE” in custom mosaic-inspired lettering, framed by stylized tile patterns and flourishes.

Central Figure: Médée occupies the middle section, standing in a heroic contrapposto pose. Her draped cloak and veiled face draw the viewer into her emotional turmoil.

Theatre and Artist Credits: The bottom band announces “THÉÂTRE DE LA RENAISSANCE” and “Sarah Bernhardt,” balancing the design and providing essential information.

Behind Médée, a circular gradient from amber to ochre evokes both the setting sun and the heat of her passionate rage. Flanking the circle, vertical mosaic-like panels ground her figure and echo the title’s border. This layered structure—text, figure, venue—ensures clarity and visual impact at a glance.

Color Palette and Light

Mucha employs a restrained yet powerful palette: warm ochres, burnt siennas, and olive greens punctuated by ivory and charcoal accents. The central circle shifts from deep rust at its core to pale gold at its edge, creating a radiant halo around Médée’s head. This chromatic glow contrasts with the cool greens of her cloak and the muted background landscape, symbolizing the dichotomy of divine wrath and earthly sorrow. Subtle metallic inks on the dagger’s blade and the title letters catch ambient light, lending the poster a jewel-like quality. Mucha’s layered approach—translucent lithographic inks on cream-toned paper—yields gentle gradations that heighten the dramatic mood.

Line Work and Ornamentation

At the heart of Art Nouveau is the sinuous “whiplash” line, and Mucha uses it masterfully in Médée. The folds of her cloak, the curling strands of her hair wreath, and the swirling patterns in the circular field all flow in continuous, dynamic curves. Mucha contrasts these organic lines with precise, geometric tessellations in the title border and side panels—creating a tension between natural movement and structural order. Line weight varies judiciously: thick outlines for the figure’s silhouette ensure legibility from afar, while fine strokes render facial features, floral details, and the dagger’s gleam. The result is a harmonious interplay of line rhythms that animate the static lithograph.

Symbolism and Iconography

Veiled Face: Médée’s partially covered face suggests hidden motives and the duality of her character—both victim and perpetrator.

Blood-tipped Dagger: The gleaming blade drips with red, foreshadowing the play’s horrific climax.

Floral Wreath and Spikes: A crown of lilies and iris petals, interspersed with radiating spikes, merges purity with danger—evoking Médée’s divine heritage and mortal wrath.

Circular Halo: The sun-like disc behind her head elevates Médée to quasi-divine status, hinting at the classical concept of tragic heroism.

Landscape Silhouette: In the background, angular hills and cypress trees reinforce a mood of desolation and fatal destiny.

Through these symbols, Mucha conveys Médée’s psychological complexity and the myth’s timeless resonance.

Typography and Graphic Integration

Mucha believed that lettering should complement imagery. In Médée, the title letters are broad, mosaic-textured blocks whose internal grid patterns echo the circular background. The diacritical marks (accents) above the És add decorative flourish. The “Théâtre de la Renaissance” subtitle employs a slender, hand-drawn serif that contrasts with the bold title while echoing ornamental linework. “Sarah Bernhardt” runs vertically alongside the figure, reinforcing the poster’s height and guiding the eye downward. Mucha’s custom typefaces integrate seamlessly with the overall design, underscoring his conviction that graphic elements and text form an indivisible whole.

Lithographic Technique and Production

Creating Médée involved multiple lithographic stones—likely eight to ten—for each color and tonal layer. Mucha’s original gouache and pencil artwork guided printers in ink selection and registration. The warm ochres, deep greens, and metallic accents required precise mixing to match Mucha’s swatches. Slightly textured, cream-toned wove paper enhanced the translucency of glazes and lent the poster a tactile quality. Printers at Champenois’s workshop maintained tight quality control, producing runs that withstood outdoor display while retaining color vibrancy. Surviving proofs reveal subtle variations in shading, testament to the artisanal nature of turn-of-the-century lithography.

Reception and Cultural Impact

Upon its release, Médée garnered acclaim from both theatrical and art circles. Reviewers in Le Gaulois and La Plume praised its “haunting intensity” and “poetic fusion of myth and modernity.” Theatre managers reported sold-out performances, attributing part of Bernhardt’s draw to the poster’s magnetic allure. Art Nouveau enthusiasts collected the sheet as decorative art, further swelling its renown. The Médée poster became a fixture in exhibitions of contemporary design, influencing painters, illustrators, and architects who sought to integrate narrative and ornament in public art.

Influence on Poster Art and Beyond

Mucha’s Médée stands as a milestone in graphic design, demonstrating that commercial posters could match the emotional power of fine art. Its success inspired contemporaries such as Georges de Feure and Eugène Grasset, who adopted Mucha’s decorative principles in their own commissions. The poster’s fusion of classical mythology with modern aesthetics resonated in Jugendstil Germany and Vienna Secession, broadening Art Nouveau’s international reach. In advertising history, Médée marks a turning point: it proved that narrative depth and stylistic unity could elevate brand communication—and theatrical promotion—to an art form.

Legacy and Modern Relevance

More than 120 years later, Mucha’s Médée continues to captivate. Original lithographs are held in major collections such as the Musée d’Orsay and the Victoria & Albert Museum. Graphic design curricula study the poster as a paragon of holistic composition, custom typography, and symbolic storytelling. Contemporary theatre producers and designers reference Mucha’s integrated approach when creating promotional materials that demand both aesthetic appeal and narrative resonance. The poster’s themes of passion, betrayal, and artistic transformation remain universal, ensuring Médée’s enduring relevance in both art history and cultural discourse.

Conclusion

Alphonse Mucha’s Médée poster transcends its role as a theatrical advertisement to become an icon of Art Nouveau and graphic design. Through masterful composition, sinuous linework, a resonant color palette, and integrated typography, Mucha captures the tragic intensity of Euripides’ myth and Sarah Bernhardt’s star power in a single, unforgettable image. The poster’s fusion of mythological symbolism and modern decorative art reshaped public expectations of visual communication, influencing generations of artists and designers. Today, Médée stands as a testament to the transformative potential of graphic art—where commerce, drama, and beauty converge to create timeless cultural artifacts.