Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

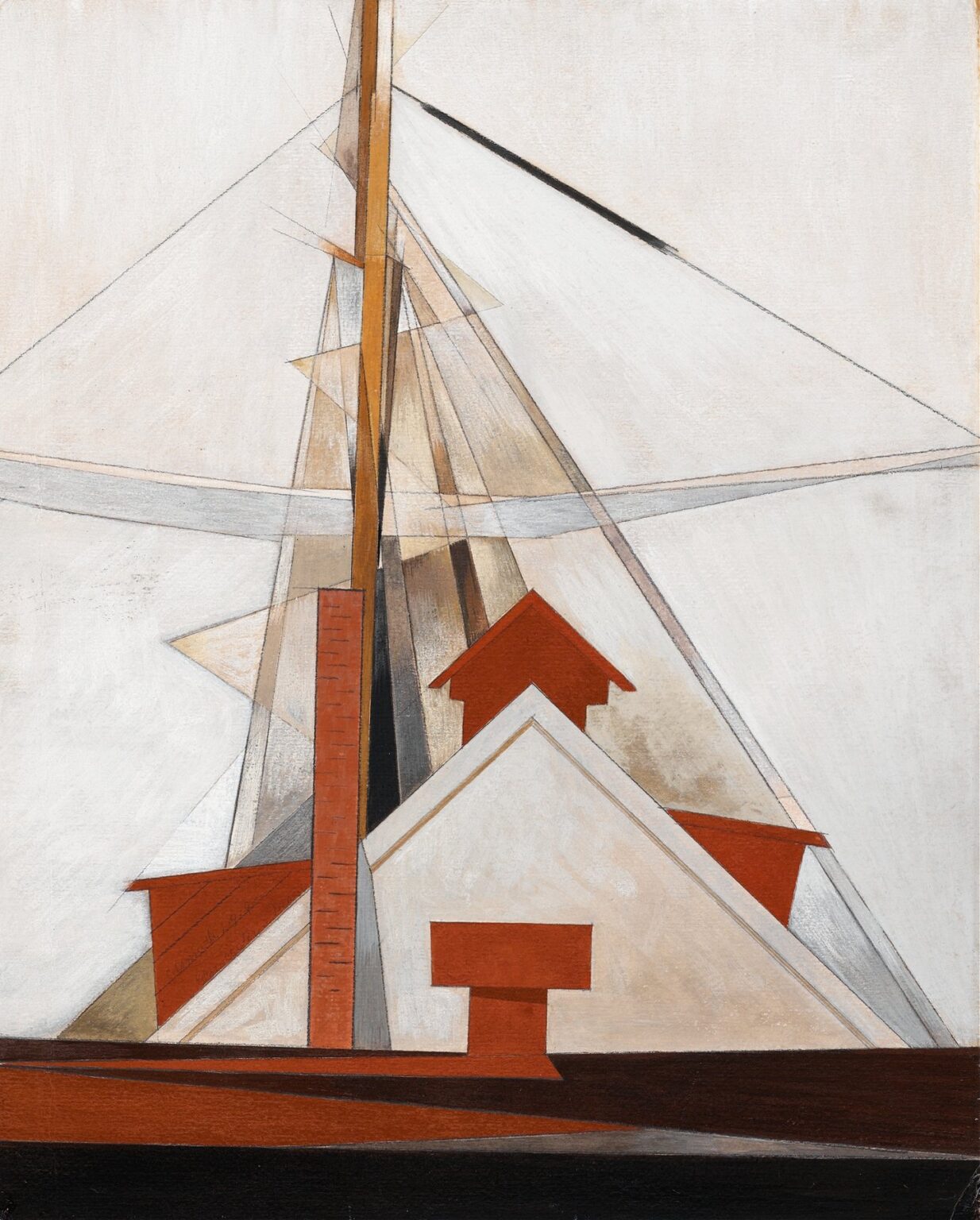

Charles Demuth’s Masts (1919) epitomizes his pioneering role in American modernism, translating the familiar rigging of a ship into a symphony of geometry, line, and light. Rendered in watercolor and pencil on paper, the work eschews literal representation in favor of dynamic abstraction, capturing the essence of nautical architecture through intersecting planes and rhythmic diagonals. Rather than depicting sails and rigging in a straightforward maritime scene, Demuth deconstructs masts and spars into crystalline facets that echo both Cubist fragmentation and Precisionist discipline. Through Masts, he not only celebrates the machinery of seafaring but also redefines still life and landscape, asserting that even the most utilitarian subject can yield profound formal innovation.

Historical Context and Artistic Milieu

In 1919, the world was emerging from the upheaval of World War I, and American artists were embracing modernist currents from Europe while forging a distinctly national identity. Demuth, born in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, in 1883, had studied in Leipzig and Paris before returning to the United States on the eve of the war. He associated with literary and artistic circles in New York and Philadelphia, including William Carlos Williams and Alfred Stieglitz, absorbing ideas from Cubism’s multifaceted perspectives and Futurism’s celebration of motion and machinery. At the same time, he gravitated toward Precisionism, an American movement that extolled industrial and architectural subjects rendered with crystalline clarity. Masts arises within this fertile confluence: it applies avant‑garde abstraction to a maritime subject, reflecting both technological optimism and a desire to distill form to its purest essence.

Demuth’s Evolving Style and Influences

Demuth’s early works display a gradual shift from representational watercolors of landscapes and figures to increasingly abstracted compositions that emphasize structure over illusion. In Paris, he encountered the fractured planes of Picasso and Braque, which inspired him to break objects into geometric segments. Futurist exhibitions in New York introduced him to the notion of dynamic movement conveyed through repeated forms and directional lines. By 1919, Demuth had synthesized these influences with his American sensibility, focusing on everyday industrial and natural motifs—bridges, factories, and, in Masts, the nautical infrastructure of ships. His style became characterized by a rigorous framework of pencil underdrawing overlaid with translucent watercolor washes, achieving a balance between the hand‑drawn gesture and mechanical precision.

Visual Description and Composition

At first glance, Masts presents a network of triangulated shapes and slender axes that converge toward the center of the composition. Two dominant vertical lines—suggestive of ship’s masts—rise from the lower margin, their pale ochre hues contrasting with the surrounding grays and warm neutrals. These upright forms support an intricate fan of diagonal shafts—representing spars and shrouds—rendered in pale grey and buff washes that overlap at varying angles. Behind this filigree, a broad triangular plane of soft beige implies the expanse of a sail caught by wind, its subtle tonal gradations evoking curvature. Beneath and around, darker horizontal bands create a low horizon or deck surface, grounding the composition. The entire scene is framed by the white of the paper, allowing the abstracted rigging to hover weightlessly, as though suspended in air rather than attached to a vessel.

Color and Light Interplay

Demuth’s palette in Masts is deliberately restrained, favoring neutral washes that emphasize form and structure over chromatic spectacle. Pale ochres and taupes convey the wooden masts and spars, while soft grays and diluted browns outline sails and shrouds. The paper’s untouched white serves as brilliant highlights, suggesting sunlight striking taut canvas. In a few areas, Demuth introduces warmer washes—subtle terra cotta or peach—hinting at the warmth of wood or the horizon’s glow. By modulating pigment density and employing both wet‑on‑wet and wet‑on‑dry techniques, he achieves nuanced transitions from light to shadow. The effect is one of airy luminosity: the rigging seems both substantial and ethereal, as if illuminated from within by the drifting light of an open sea.

Line, Form, and Abstraction

While watercolor provides tonal depth, Demuth’s pencil work defines the painting’s architectural backbone. Fine, precise lines trace the outlines of masts, the edges of spars, and the triangular facets of sails. In places, parallel hatching suggests the grain of wood or the tension of rope, while faint construction lines extend beyond painted planes, revealing the artist’s process and the underlying geometry. The fragmentation of form—each object rendered as an assembly of flat, angular surfaces—aligns with Cubist principles, inviting multiple perspectives to coexist on a single plane. Yet Demuth tempers this fragmentation with a minimalist elegance, ensuring each line and plane contributes to an overarching sense of harmony rather than chaos.

Maritime Motifs and Symbolism

Ships and the sea have long symbolized exploration, commerce, and human ingenuity in the face of nature’s vastness. Masts focuses on the infrastructure that enables seafaring—the masts, spars, and rigging—rather than the hull or deck, underscoring the interplay of force and counterforce that propels a vessel. The painting abstracts these motifs into a visual architecture, evoking both the potential energy of wind‑blown sails and the meticulous engineering that tames that power. In the post‑war era, ships represented global connectivity and the promise of peaceful exchange, even as mechanized warfare had showcased technology’s destructive capacities. Demuth’s elegant rendering thus offers a tempered celebration of technology harnessed for productive, rather than destructive, ends.

Technique and Material Considerations

Demuth’s choice of watercolor on high‑quality wove paper reflects his mastery of a medium often associated with spontaneity rather than structural precision. He begins with a careful pencil underdrawing, mapping out the intersections of masts and shrouds before any pigment touches the surface. The watercolor layers are built up gradually: initial light washes establish the broad planes, followed by more saturated tones that define edges and add weight. In certain areas, Demuth lifts pigment to create clean edges or emphasize highlights, and he occasionally allows pigments to granulate, producing subtle textures reminiscent of weathered wood or salt‑air corrosion. The result is a surface that balances crisp, mechanical order with the delicate verve of hand‑applied wash.

Comparison with Related Works

Masts sits alongside Demuth’s other abstracted architectural compositions from the same period, such as The Prodigal Son interior studies and his Bermuda series watercolors. Compared to his industrial scenes—towering factories, silos, and bridges—Masts evokes a lighter, more lyrical atmosphere, as though the subject floats in open sky rather than tightening industrial grids. Yet the formal vocabulary remains consistent: intersecting planes, slender linear accents, and restrained color punctuated by warm highlights. This consistency underscores Demuth’s conviction that modernist abstraction could be equally applied to natural, urban, and maritime motifs without sacrificing formal rigor.

Viewer Engagement and Interpretive Invitation

Although abstract in approach, Masts retains enough referential cues—vertical poles, triangular sail shapes—to anchor viewer interpretation. Observers may first recognize the joyous geometry of rigging, then gradually discern echoes of masts, sails, and wind. The whitespace surrounding the network of forms invites contemplation of negative space as integral to the composition, mirroring the emptiness of sky and sea. The work encourages a dynamic engagement: one’s gaze traces the diagonal lines as though following the path of wind across canvas, feeling the tension in each shroud, the lift of each sail. Through this active viewing, Demuth transforms a static paper into a vivid tableau of maritime energy.

Legacy and Significance

Masts exemplifies Charles Demuth’s contribution to early American modernism, demonstrating that abstraction could illuminate the structural poetry of everyday subjects. While Demuth is often celebrated for his later Precisionist cityscapes and typographic works, his watercolors from 1918 to 1920—of which Masts is a highlight—reveal his experiments in merging Cubist fragmentation with soft, atmospheric wash. These works influenced contemporaries and successors who sought to explore industrial and nautical themes without resorting to photorealism. Today, Masts remains a touchstone for artists and historians interested in the intersections of watermedia, modernist abstraction, and maritime iconography.

Conclusion

In Masts (1919), Charles Demuth distills the essence of nautical architecture into a vibrant interplay of line, plane, and color. Through the elegant fragmentation of masts, spars, and sails, he captures both the mechanical precision and ethereal beauty of seafaring equipment. The painting stands at the crossroads of Cubist deconstruction, Precisionist order, and watercolor’s luminous potential, offering a timeless meditation on technology harnessed to human aspiration. As viewers continue to trace its intersecting lines and drifting washes, Masts endures as a masterful testament to Demuth’s vision and the broader possibilities of American modernist art.