Image source: wikiart.org

First Impressions: A Dark Dress, a Blue Spark, a Calm Field of Air

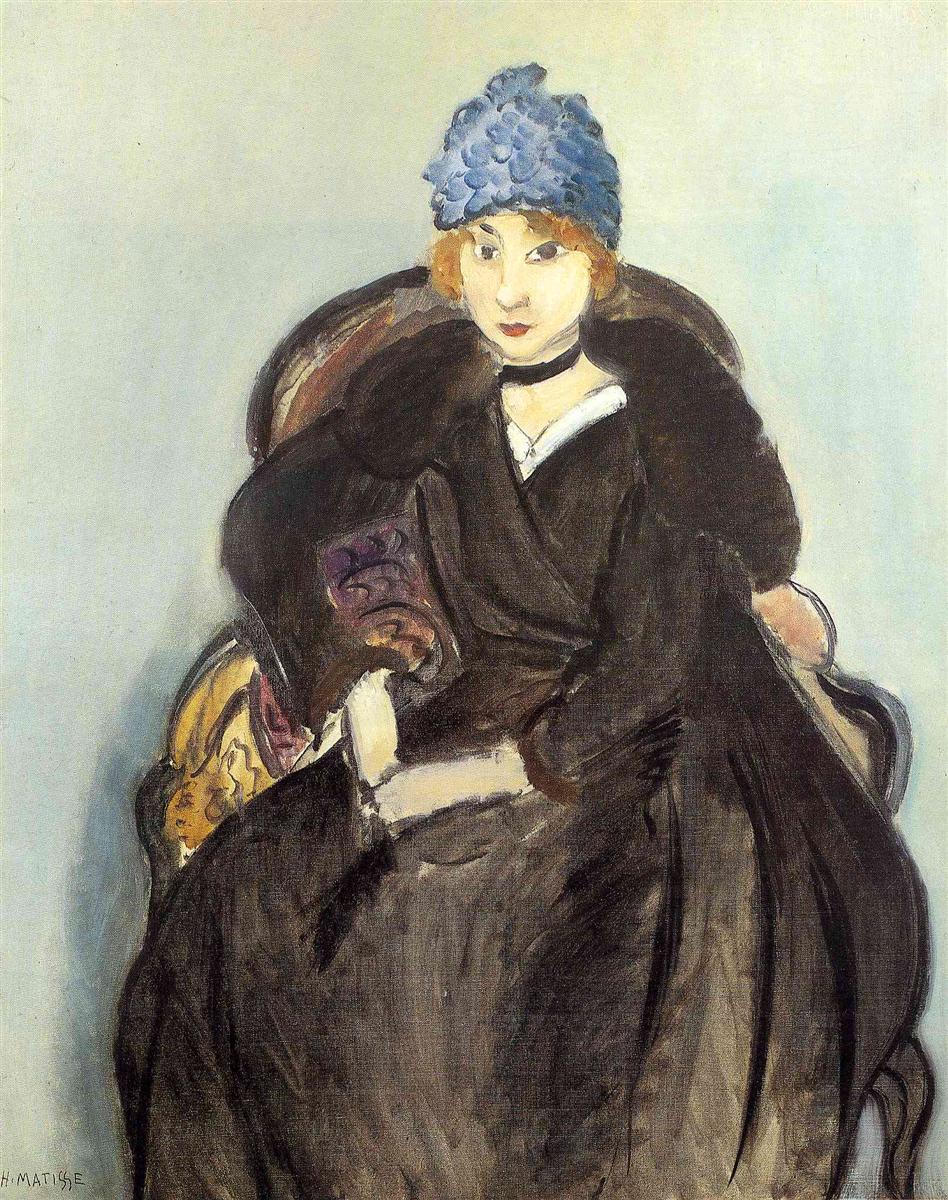

At first glance “Marguerite Wearing a Hat” appears disarmingly simple: a young woman sits deep in an upholstered armchair, enveloped in a dark dress whose mass fills the lower two thirds of the picture. Her face is small and luminous, framed by a short black choker and the textured pop of a blue hat that catches the light like a cluster of petals. The ground is a pale, even climate of blue-gray, free of architectural distraction. One sees three forces at play immediately: the weight of the dress as a stabilizing triangle, the clear oval of the face as the point of focus, and the hat as a chromatic keystone that locks the composition together. The sensation is poised and modern. Nothing pleads for attention; everything sits in measured relation.

1918 and the Turn to Nice

The year 1918 marks a pivot in Henri Matisse’s art. After the carved severity and high-contrast experiments of the mid-1910s, he arrived on the Côte d’Azur and began what would become the Nice period. The key changed. He traded fireworks for tuning, bravura for breath, and he used black as a positive, structural color rather than a mere outline. Portraits from this moment—often of his daughter Marguerite—prove the point. They are intimate without anecdote, calm without blankness, and built from a handful of exact relations: a moderated palette, visible brushwork, shallow space held close to the plane, and a respect for the sitter’s privacy. “Marguerite Wearing a Hat” condenses that new grammar into a single, lucid statement.

The Sitter and the Ethical Space of Looking

Marguerite Matisse posed for her father across two decades, and her presence anchors some of his most searching portraits. Here, she is neither idealized nor dramatized. The gaze is frank but uninsistent; the mouth is composed; the tilt of the head is slight. Matisse’s ethics of looking—attention without intrusion—governs every choice. The chair wraps but does not swallow; the costume is declarative but not elaborate; the background offers air rather than narrative. The painting’s humanity rests on that restraint.

Composition: Pyramid, Oval, and Brackets

The composition reads cleanly at a distance because its architecture is clear. The black dress forms a broad pyramid anchored to the canvas’s bottom edge. Inside that pyramid the white V of collar and shirtfront rises like a small light well toward the face. The face itself is a pale oval placed slightly above center, and the blue hat crowns it as a rounded keystone. Two bracket forms, left and right—the carved arms of the chair—curve forward to hold the figure and echo the hat’s scalloped silhouette. The result is a set of nested forms: chair around dress, dress around torso, collar lifting to head, hat sealing the whole. The eye settles immediately and then begins to wander along the interior rhythms of fold, curve, and contour.

The Hat as Chromatic Keystone and Character

The blue hat is not a mere accessory; it is the painting’s chromatic hinge. Its cool, bright register pulls the face into focus against the otherwise dark costume and pale air. Texturally, Matisse builds the hat from short, rounded touches that suggest a soft, petal-like surface—a lively contrast to the long, slower drags used in the dress. That change of tempo makes the head feel alert. A few warmer notes around the fringe of hair and the faint rose at the lips echo the hat’s brightness in smaller keys, keeping the head from floating free of the rest.

Palette: Tuned Temperatures, Not Loud Saturations

The chord is lean and sophisticated. The ground is an even, chalky blue-gray, brushed in thin veils that allow the support to breathe and keep the room airy. The dress is an expansive register of blacks—brown-black in the shadowed folds, blue-black along the outer curves, and thin charcoal passes where light skims the fabric. The chair introduces warm ochres and violets in small, upholstered flashes that never challenge the dominance of the dress. Flesh is built with pearly whites, soft ochres, and modest pinks, cooler at the temple and jaw, warmer where cheek meets light. The hat brings a concentrated blue that never shrieks; it simply completes the chord. Because saturation is moderated everywhere, temperature does the expressive work: cool air behind warm face, living blacks against pale skin, blue crown cooling the head while sharpening it.

Black as a Positive, Structural Color

Matisse’s mastery of black is decisive here. The dress is not an undifferentiated void; it is a field of living darks that turn with the body. Near the collar, black warms toward brown; along the hem and at the right, it shifts cooler toward blue; in the deepest folds it thickens to a near-matte note that absorbs light. Shorter black accents—the choker, the inner edge of the eyelids, a tight crescent at the lower lip—supply the painting’s bass rhythm. They keep the airy palette from drifting and they stabilize neighboring colors without imprisoning them in outline.

Brushwork: The Visible Time of Making

The surface carries the time of its construction. In the background the brush moves in broad, slightly diagonal pulls that leave faint ridges and a breathable ground. In the dress, strokes run longer and heavier; some passes are semi-transparent, creating a glaze that lets under-tones warm the fabric. The chair is painted with brisker, curved touches, appropriate to carved wood and upholstery. In the head and hat the strokes shorten, interlocking to shape features while leaving a lively grain. Nothing here is polished to anonymity. Each zone keeps its tempo—air slow, garment legato, chair syncopated, face articulate—so the portrait breathes.

Edges and Joins: How Forms Meet Air

Edges are tailored like seams in a good coat. Where hair meets the blue ground, the contour is sharp at the crown and breathed at the temple, so the head sits and also shines. Where dress meets chair, the seam alternates between firm and softened, suggesting shifting focus and the interplay of dark upon dark. Where collar meets flesh, a luminous edge remains—perhaps underpaint catching light—giving the sensation of a starched white catching air. At the sleeves and lap, dragged paint leaves slight halos that read as reflected light. These varied joins prevent the large, simplified forms from reading like pasted cutouts; they seat the figure in a shared atmosphere.

The Chair as Rhythmic Counterpart

The armchair provides geometry, color, and rhythm. Its curving arms echo the hat and guide the eye back toward the head. Its upholstery offers brief, patterned notes—violets and ochres—that punctuate the field of black without breaking it. Its inner curve on the left creates a pocket of shadow that deepens the dress’s mass while clarifying the boundary between figure and ground. Through these modest means, the chair becomes the figure’s partner rather than a prop.

The Face: Specificity Through Abbreviation

Matisse achieves likeness without pedantry. The eyes are decisive dark almonds; small highlights catch at their inner corners and lend life. The nose is a planar wedge, the mouth a measured shape with a cooler note on the lower lip. The chin carries a faint, soft shadow that keeps the oval from flattening. Marguerite’s hair is stippled at the edges, a light halo at the forehead ceding to darker locks behind the ear. The expression is composed and alert, private but available—typical of Matisse’s best portraits, which refuse theatrical psychology in favor of human presence.

Background as Air, Not Architecture

By denying furniture, moldings, and the busy pleasures of pattern, Matisse lets air do the work of space. The blue-gray surround is a climate more than a wall. Its neutrality amplifies the calibrations elsewhere: it cools the hat, warms the face by contrast, and allows the blacks to read as colored masses rather than as holes. Because the ground is a single, continuous field, the portrait retains a modern, designed surface while remaining completely inhabitable.

Rhythm in the Dark

The large black mass of the dress could have deadened the painting, but Matisse animates it with a rhythm of folds that converge toward the lap. Subtle diagonals, long verticals, and a few curving seams create a slow pulse that rises toward the head. This interior movement keeps the eye traveling and gives the body both weight and breath. The dress is not armor; it is weather moving across dark cloth.

Dialogues with Tradition Without Quotation

The picture converses with several traditions yet never quotes them. The seated pose in a deep chair nods to portrait conventions from Ingres to Manet, but the simplification of form and the flat, breathing ground bring the image squarely into the twentieth century. The use of black as a color and not merely an outline recalls Japanese print design; the construction of volume by adjacent planes rather than by blended shadow remembers Cézanne. These influences are thoroughly assimilated into Matisse’s grammar of relations: calm achieved by measured contrast, presence summoned by a few decisive notes.

Relation to Other 1918 Portraits

Set beside “Brown Eyes,” “Marguerite in a Fur Hat,” and “Woman with Dark Hair,” this canvas strikes a middle key. Like the fur-hat portrait, it features a structural choker and a cool ground; like “Brown Eyes,” it sets a compact head above a dominant dark garment; like the balcony portraits, it relies on a single strong color accent—in this case the blue hat—to energize a restrained palette. What distinguishes the present work is the amplitude of the dress and the centrality of the chair, which together turn the figure into a quiet monument.

Material Evidence and the Courage to Stop

Traces of revision remain visible and lend life: a re-drawn edge of the hat where blue meets air, a broadened fold in the dress corrected by a darker pass, a small restatement at the collar’s V, a reclaimed slice of background around the shoulder. Matisse never polishes these decisions into oblivion. He stops when the relations feel inevitable, not when the surface is cosmetically smooth. That earned inevitability is the portrait’s deepest authority.

How to Look: A Slow Circuit Through the Painting

Enter at the choker and let its firm dark hinge lock head to body. Rise into the face, catching the small cool highlight on the lower lip, then step into the blue hat where short, lively strokes gather light. Travel down the left contour through a softened seam into the chair’s warm curve; cross the dress’s slow diagonals to the right arm where a pale cuff breaks the dark; descend to the lap where folds converge; and then climb the collar’s white V back to the face. Repeat the loop. With each circuit the painting reveals itself as cadence rather than as inventory.

Why the Portrait Still Feels Contemporary

A century later, the image looks fresh because its clarity aligns with contemporary seeing. Big shapes read at once; color is nuanced rather than loud; process remains visible and honest; space is shallow enough to coexist with photography and graphic design. Most importantly, the picture trusts a small set of exact relations—pale oval against black mass, blue crown against gray air, warm chair notes around the perimeter—to carry the full burden of presence. That trust is Matisse’s modernity.

Conclusion: Presence Built from Essentials

“Marguerite Wearing a Hat” distills Matisse’s early Nice vocabulary into a portrait of lasting quiet. The dress’s dark architecture, the chair’s curved brackets, the blue hat’s cool spark, the choker’s decisive hinge, the breathing field of ground, and the measured brushwork together create a humane and lucid design. Nothing is redundant; nothing shouts. The painting invites long companionship—the rare quality of art that steadies rather than exhausts—and it demonstrates how a few true relations, placed precisely, can make a person felt across time.