Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

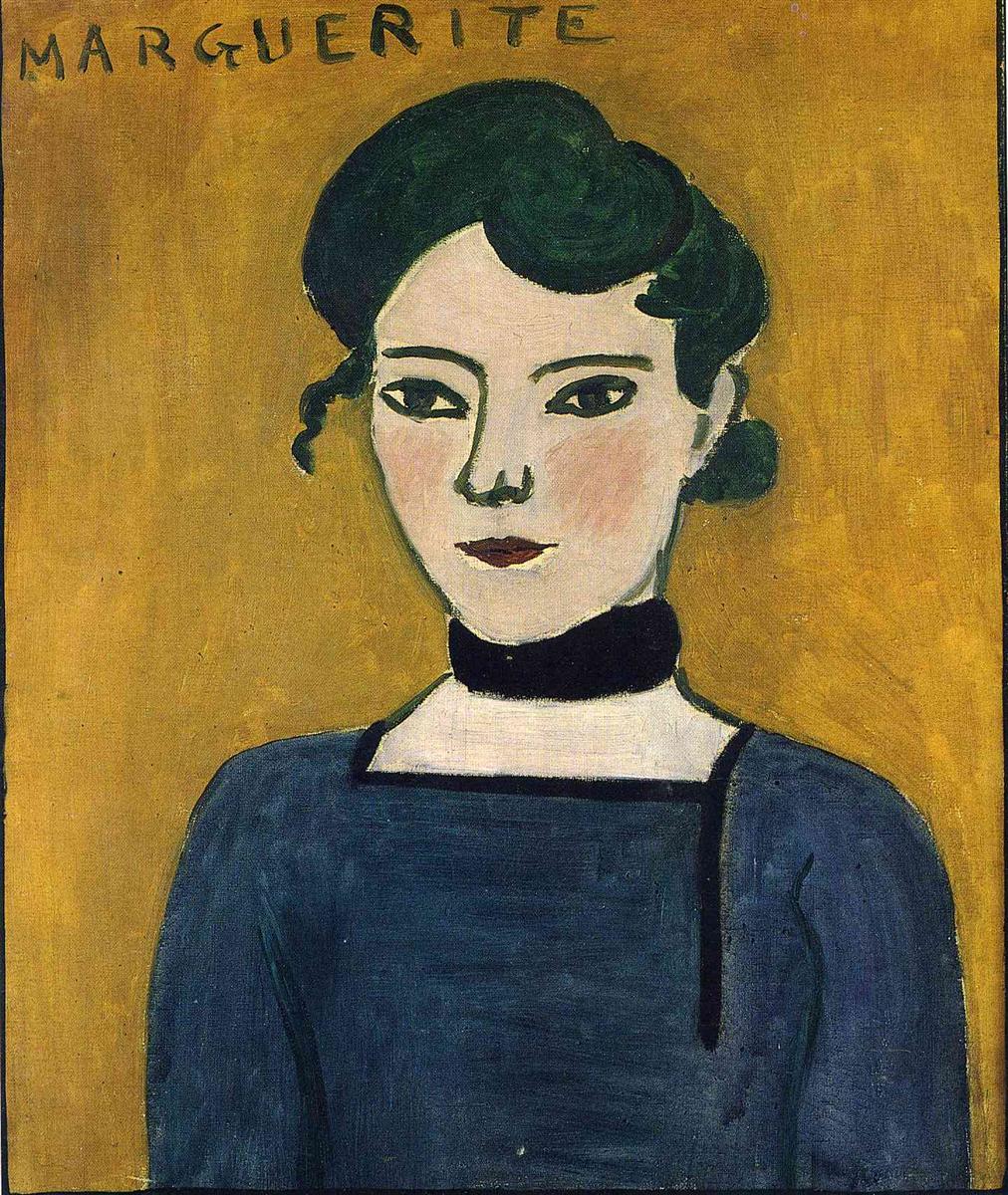

Henri Matisse’s Marguerite (1907) is a small, frontal portrait with outsized presence. The sitter’s name is written at the top like a headline, the background is a saturated field of yellow ocher, and the young woman meets the viewer with a calm, level gaze. The composition is almost startlingly simple: head and shoulders, dark dress, a black choker that cinches the neck like a drawn line, and hair gathered into stylized coils. Yet within this restraint Matisse condenses many of his 1907 ambitions—firm contour, reduced modeling, chromatic courage, and the transformation of a personal subject into a modern emblem. What might have been a conventional likeness of his daughter becomes a crucible where color, line, and intimacy are tested and refined.

Historical Context

The year 1907 marks a juncture in European art and in Matisse’s own trajectory. Two years after the explosive debut of the Fauves, he was moving beyond pure chromatic shock toward a more deliberate structure. While many avant-garde artists turned to fracture and dissonance, Matisse pursued equilibrium: how to retain the vitality of unblended color and decisive contour while granting figures a monumental calm. Portraiture offered a perfect arena. In Marguerite, he uses a close, iconic format to explore how few elements are needed to project character and presence. The painting belongs to a cluster of works from these years in which he reimagines the portrait as a field of bold shapes whose harmony matters as much as resemblance.

Subject and Identity

Marguerite Matisse, the artist’s eldest child, appears in many of his works across decades. This 1907 image crystallizes the daughter not as biographical note but as motif. Her features are pared to essences: a pale, oval face; almond eyes set under simplified brows; a small mouth painted like a dark petal; hair rendered as sculptural masses. The choker and the modest, squared neckline set a sober tone, while the name “MARGUERITE” across the top simultaneously identifies and monumentalizes her. Matisse does not court anecdote or psychological display; he seeks a presence that is cool, poised, and enduring. The portrait’s intimacy springs from proximity and steadiness rather than from narrative details.

Composition and Framing

The format is a classic half-length bust cropped tightly at the shoulders. Matisse centers the head slightly high in the frame so that the hair nearly grazes the upper inscription. This upward placement lends dignity and concentrates the viewer’s attention on the face. The body is composed as a stable trapezoid: broad, dark torso tapering to the bright, narrow column of the neck. The inscription forms a shallow arch that echoes the rounded hairline and leads the eye back down into the face. The frontal pose eliminates directional movement; instead, the picture’s energy comes from the tension between rectangular field and rounded forms, between flatness and subtle relief.

Palette and Color Strategy

Matisse limits the palette to a handful of assertive tones: mustard-ochre for the background, deep blue-green for the dress, black for hair, choker, and contour, a chalky white for the collar and neck, and delicately warmed pinks in the cheeks and lips. This economy heightens the effect of each color. The yellow background advances and flickers around the head like a halo, but because it is a full, earthy ocher rather than lemon, it confers warmth without glare. The dark dress supplies a cool mass that grounds the image. Black is not a neutral absence here; it is an active pigment that carves the features and punctuates the composition. The small reserves of white—especially at the throat—act like a bright hinge that articulates head and torso. Flesh is not modeled through a long scale of tones; it is evoked by a flat, lightly blushed field that gains life through adjacency to surrounding colors.

Contour and Drawing

The portrait’s authority rests on contour. Matisse draws with the brush in firm, unbroken lines: the jaw traced by a single curve, the brow and nose implied by continuous arcs, the eyelids sharply defined so that the eyes command attention without fuss. The black choker doubles as a line drawn around a cylinder; its perfect horizontality steadies the composition and heightens the vertical lift of neck and head. The artist allows small asymmetries to remain—the left eye fractionally higher, the hairline uneven—because they keep the image alive. Contour here is not a cage for color but a partner, a structural device that lets flat planes carry emotional weight.

Surface and Brushwork

Although the shapes are simple, the paint surface is far from inert. The background is brushed in broad, slightly varied strokes that let underlayers breathe through, creating a luminous, granular field rather than a mechanical flat. In the dress, darker and lighter strokes stack in gentle diagonals, giving the textile a quiet movement. The flesh is laid thinly; slight variations in pressure and pigment density create a soft, breathing irregularity that substitutes for traditional modeling. Matisse resists polish. He wants the viewer to sense the painting’s making—to see how a few deliberate sweeps of the brush can propose a world.

The Mask-Like Face

Viewers often describe Matisse’s faces from this period as mask-like. The term suits Marguerite, but it should be understood as praise rather than critique. The mask is a device of concentration. By compressing features to a few signs—arched brows, almond eyes, a dark, closed mouth—Matisse gives the face a serene inevitability. The “mask” refuses the fleeting expression and instead radiates a stable mood. In this portrait the mood is composed and slightly enigmatic, an inward calm that withstands the bright surround. The effect allows the painting to operate on two levels: as an icon whose fields and lines harmonize abstractly, and as a likeness whose stillness suggests intelligence and reserve.

Inscription as Design

The handwritten “MARGUERITE” across the top is more than identification. Its letters, scumbled in dark paint, become a frieze that locks the head into place. The spacing is irregular and lively; the rugged forms of the letters rhyme with the brushy grain of the background. By integrating text into the image, Matisse courts a modern, graphic sensibility that anticipates his later joy in typography and cut-paper forms. The inscription also collapses distance between painting and viewer: the picture names the person you meet, as if making an introduction. It is at once personal and declarative, a father’s label and an artist’s compositional tool.

Costume and the Black Choker

The dress is rendered as a blocky shape with minimal tailoring, its squarish neckline echoing the canvas’s edges. The black choker is crucial. It cinches the neck with an intensity that is formal, not oppressive, transforming anatomy into a clear geometrical juncture. The band’s dark density sets off the pallor of the throat and face, heightening their luminosity. It is also a repeated motif: the same black recurs in hair, eyebrows, and pupils, tying the portrait together through a network of accents. The restraint of costume shifts the expressive burden to color relationships and to the sitter’s steady gaze.

Background as Active Field

Instead of a depicted room or landscape, Matisse uses a single field of ocher that vibrates with small shifts in value and temperature. This background does important labor. It refuses illusionistic depth, keeping the sitter firmly on the picture plane. It also offers chromatic counterpoint to the blue-green dress; the two hues, placed in opposition, make each other vivid. The ocher’s warmth implies light without specifying a source; highlights on face and collar feel inevitable rather than observed. The background thus functions like a stage light that is everywhere at once, bathing the figure in a generalized glow.

Space, Flatness, and Modern Presence

Traditional portraits build volume through shadow and create space with perspective cues. Marguerite instead asserts flatness and proximity. The sitter is not placed in a receding room; she is set against a plane and held there by contour. This results in a distinctly modern kind of presence—closer to a poster or icon than to a window view. The effect is not cold; on the contrary, the closeness and clarity feel intimate. The viewer encounters Marguerite directly, as if the painting were a face-to-face meeting distilled to essentials.

Emotional Tone and Restraint

The portrait’s emotional climate is quiet but not neutral. The eyes, sharply drawn and slightly darkened beneath the brows, project alertness. The closed lips keep the mood composed; the faint flush in the cheeks and the delicate warmth of the skin prevent austerity. Everything signals poise rather than display. This moderated tone is consistent with Matisse’s broader project in 1907: to locate drama not in anecdote or theatrical gesture but in the orchestration of forms. The painting’s feeling resides in balance itself—in the way the black choker steadies the head, in the rapport between yellow ground and green dress, in the exactness of the eyes.

Comparisons within Matisse’s Oeuvre

Placed alongside the earlier, more explosive Fauvist portraits, Marguerite reads as distilled and classical. It shares with works like the famed portraits featuring a “green stripe” the commitment to color as structure, yet it renounces aggressive color dissonance in favor of controlled harmony. It also looks forward to later portraits and interiors where figure and field are bound by large, unbroken shapes and by calligraphic line. The inscription anticipates the graphic sensibility that would culminate in the cut-outs, where words and images often coexist as equals. Across this continuum, Marguerite remains a constant muse through whom Matisse tests new balances.

The Year 1907 and Modern Dialogues

In 1907, many artists sought new ways to simplify or fracture the figure. Matisse’s answer in Marguerite is neither fragmentation nor naturalistic finish but clarity. He draws inspiration from sources that privileged essential shape—ranging from non-Western sculpture to medieval icons—without quoting them directly. The mask-like face, the frontal pose, and the flat field acknowledge those lineages while remaining wholly modern. Where others cultivated shock or aggression, Matisse cultivated serenity built from bold means.

Light, Value, and the Refusal of Chiaroscuro

The portrait disperses light evenly. There are no dramatic cast shadows, no deep rifts of value. Instead, Matisse uses a few value steps—dark dress and hair, medium ground, light skin and collar—to produce a crisp hierarchy. White at the throat and subtle pink at the cheeks provide the main value contrasts within the face. This pared-down scale has a clarifying effect: the eye reads the picture instantly, then lingers on subtleties of edge and temperature. The refusal of academic chiaroscuro is not a dismissal of light but a redefinition of how light can operate in painting—as a condition expressed through color relationships rather than through carved shadow.

The Psychology of Gaze

Because the face is simplified, the eyes carry potent charge. They are positioned slightly high, tilted with a hint of asymmetry, and ringed by strong lids. Their directness gives the viewer a sense of encounter without confession. The gaze is steady, not piercing; the expression is reserved, not guarded. In removing descriptive detail, Matisse paradoxically opens the portrait to more readings: intelligence, composure, youthful self-possession. The ambiguity is generous. It allows Marguerite to exist as both specific person and type, a modern heroine of calm.

Material Presence and Scale

The modest size of the canvas intensifies its effect. Held close, the brushwork’s grain and the chalky respiration of the paint become palpable. The painting reads almost like a panel or plaque, an object with weight rather than a window into space. This object-quality pairs with the inscription to give the work a declarative voice. It is as if the painting announces itself: here is Marguerite, rendered with as few means as possible, protected by the clarity of contour and the quiet authority of color.

Legacy and Continuing Relevance

Marguerite continues to speak to contemporary viewers because it embodies a lesson still urgent today: simplicity can be the most daring path. Its economy offers a counterexample to the assumption that complexity equals depth. Designers, painters, and photographers alike can learn from its orchestration—a limited palette tuned to maximum effect, a decisive line that grants structure without fuss, a balance between graphic flatness and human warmth. For those interested in Matisse’s biography, the painting reveals how familial intimacy becomes artistic rigor; for those interested in modernism, it shows how portraiture can be reinvented without abandoning recognition.

Conclusion

Henri Matisse’s Marguerite distills portraiture to essentials and in doing so enlarges it. A few colors, a few lines, a name written across the top, and a face that meets the viewer without flinching—these elements together create an image of quiet force. The painting demonstrates the artist’s 1907 synthesis: keep the audacity of color, keep the firmness of contour, but channel both into equilibrium rather than spectacle. The result is an icon of modern poise, intimate and monumental at once, where a young woman’s steady gaze and a father-artist’s disciplined love are preserved in the durable language of line and plane.