Image source: wikiart.org

First Look: A Portrait That Thinks in Color

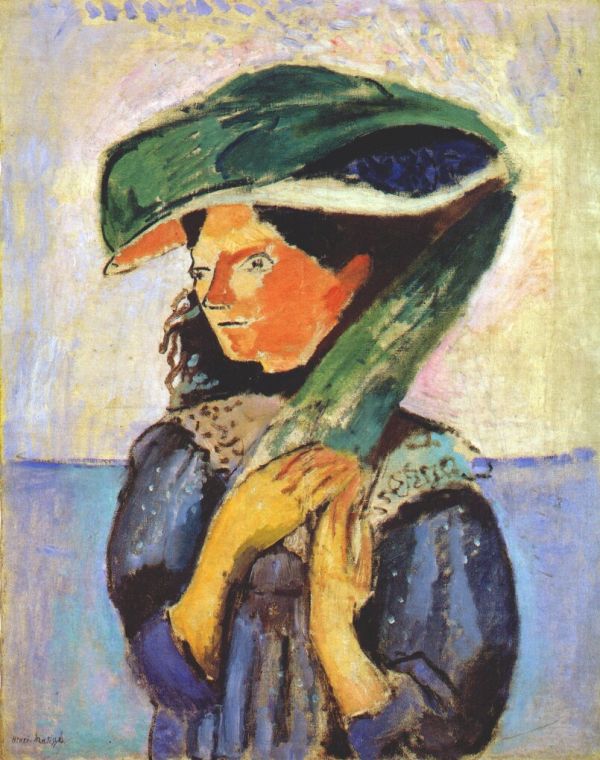

“Margot” greets the viewer with a direct, almost emblematic presence. A young woman fills the vertical format from the wide sweep of her green hat to the compressed knot of her hands. Her face is mapped in hot oranges and coral reds, her dress is a deep nocturne of blues and violets, and the hat flares in viridian with dark, inky shadows. Behind her, a narrow horizon of sea-blue crosses a pale, luminous field so the figure breathes in open air rather than in a cramped interior. Even before one studies the paint handling, it is clear that Henri Matisse has replaced traditional modeling with relationships of hue and temperature. The portrait is not drawn and then colored; it is built out of color from the start.

1906: After the Fauvist Breakthrough

The year 1906 sits directly after the incendiary Salon d’Automne of 1905, where the public first encountered the blazing palettes of the Fauves. In that context “Margot” functions like a proof of concept. Matisse no longer paints to shock but to consolidate. He asks whether the same daring chromatic grammar that organized a summer landscape can also carry the subtler work of portraiture. The answer in “Margot” is a confident yes. Saturated pigments, used without heavy blending and placed in deliberate complements, substitute for chiaroscuro. The result is a portrait that keeps the face vivid and legible while stripping away academic shading and anecdotal detail.

The Subject: Poise Without Ornament

The sitter is not overloaded with narrative props. She stands at the water’s edge, her head turned slightly to the left, her gaze directed past the viewer in quiet concentration. She holds an elongated scarf that streams down from the hat’s brim; the hands fold it—a small, tender action that becomes the painting’s hinge. The dress’s high collar and the modest cascade of the fabric set a tone of self-contained dignity. Matisse has no interest in social role-play; there is no jewelry or elaborate background to signal status. Presence itself is the subject, rendered in confident chords of color.

Composition: A Stable Column Cut by a Horizon

The format is a tall rectangle, and Matisse anchors it with the column of the figure. A nearly horizontal line of sea crosses the panel at mid-height, turning the upper background into a pale sky and the lower background into cool water. That single band provides the landscape’s entire architecture. The hat’s brim sweeps diagonally, echoing the tilt of the scarf; the hands tighten the base of the composition with interlocking curves. The hat, face, and hands create a triangle of focal points that guide a smooth loop for the eye. Because the background is restrained, the figure reads with clarity and the color relations stay unclouded.

Color Architecture: Complements Instead of Shadows

Orange skin against blue dress, green hat against a pale lilac sky—these are the structural chords. The face is not modeled from dark to light but from warm to cool. Coral and orange dominate, cooled by minty halftones along the cheek and jaw; the shadow under the brim leans toward cobalt rather than brown. The dress holds a suite of blues—Prussian, ultramarine, and violet—that settle the body’s mass. The viridian hat supplies a cool complement to the face’s warmth and becomes the portrait’s emotional key: it is assertive, almost architectural, yet softened by the scarf’s fluid fall of green. Because pigments remain clean and the joins between zones are visible, edges arise where temperatures meet. A green stroke crossing an orange plane becomes the nose bridge. A midnight-blue flick along the chin edge clarifies the turn of the head. You feel form without graphite.

The Hat and Scarf: A Single Gesture of Movement

The hat is no mere fashion accessory. Matisse treats it as a mobile canopy that shapes the sitter’s silhouette and sets the whole portrait in motion. The brim’s bright, almost leaf-like underside touches the cheek with a wedge of warm ocher, explaining how the light bounces. The scarf descends in a long diagonal that meets the clasped hands, and its striations of greens and bluish shadows repeat the sea behind. This visual rhyme marries figure and place. The hat also supplies drama—its deep dark inset at the right edge is one of the strongest values in the picture, a cave of color that gives the rest of the palette room to glow.

Hands as Structural Poetry

Matisse constructs the hands with extreme economy. A few ocher planes and abbreviated blue shadows describe knuckles and tendons; the fingers interlace not as anatomically perfect digits but as curled silhouettes. Their position closes the lower half of the painting like a clasp. They also enact a gentle narrative: Margot is holding herself together against the breeze, which is suggested by the scarf’s pull and the hat’s tilt. The gesture animates the portrait without forcing theatrical expression into the face.

Background: Air That Carries the Figure

The background is a major actor even though it looks minimal. Pale cream slides into violet haze near the top edge; a very thin blue band suggests water—and with it, the sea culture of Collioure and the south. This background is handled thinly so that the surface breathes. It is not a “neutral” void but a climate that lets the figure’s color read as light rather than coated pigment. Notice how the slight halo of warm pink behind the head prevents the dark hair and green hat from cutting a harsh silhouette; it is a tiny cushion of atmosphere that keeps the portrait hospitable.

Brushwork: Varied Touch as Description

The paint handling signals substance. The dress is brushed in long, slightly vertical swathes that mimic the fall of cloth; the face is made of compact planes laid decisively so that each change of direction—the cheekbone’s break, the eye socket’s dip, the jaw’s angle—registers. The hat mixes both languages: thick, pressure-heavy strokes for the dark interior, sweeping lighter strokes for the brim and scarf, as if the hat caught and dispersed the wind. The background is scumbled, thin enough for the texture of the support to glow through, turning air into a tactile presence. The material diversity is not decoration; it is the way Matisse differentiates skin, cloth, felt, and air without slavish detail.

Light Without Chiaroscuro

Traditional portraiture depends on a consistent beam carving light and shade across planes. In “Margot,” illumination is more like a high, even seaside brightness that compresses shadows and amplifies color. The brim generates a cool band across the forehead, the nose turns with a small cooler stroke, and the entire left side of the face is warmed rather than darkened. The white highlights are scarce and strategically placed: a sharp note at the eye, a fairer edge along the cheek that lifts it from the scarf, a glancing touch on the knuckles. Most of the “light” is performed by color temperature and adjacency.

Psychology Through Structure

Matisse rarely courts narrative psychology, yet “Margot” conveys a distinctive mood. The gaze is measured, not confrontational; the mouth is neither smiling nor grim; the hands are busy without anxiety. The feeling is thoughtful self-possession—an inwardness that makes sense beside the sea. You do not need precise facial modeling to sense character. The tilt of the hat, the long diagonal of the scarf, and the compressed triangle of hands are enough to situate Margot in a breeze, adjusting to the world with calm focus.

Relationship to Matisse’s Other Portraits

Compared with “Woman with a Hat” (1905), “Margot” has a quieter palette and a steadier structure. The 1905 picture trumpets color’s audacity; this one demonstrates its fluency. Set beside “The Green Line (Portrait of Madame Matisse),” it shares the principle of a single chromatic seam doing the work of anatomy, but the effect is gentler. The green of Margot’s hat plays the structural role that the vertical green stripe plays in “The Green Line,” yet here the green is folded into a believable article of clothing and echoed in the landscape. The experiment has become a language.

Design Intelligence: Ornament Without Pattern

Matisse’s love of the decorative arts shows up in the portrait’s organization. The scalloped collar is treated like a quick motif, the dress’s dotted highlights like a sprinkling of pattern, the scarf’s stripes like a textile design. None of these become fuss. They are there to guide your eye and to knit figure and ground. The entire portrait embraces the decorative principle that unity across the surface matters as much as depth: the sea’s blue is in the dress, the sky’s lilac finds a whisper in the collar, the hat’s green is reflected in the scarf and stabilized by the dark insert that anchors the right side. Ornament functions as structure.

Space and Scale: Shallow Depth, Big Presence

The shallow space—sea band, pale air, frontal figure—keeps the portrait from retreating. Margot stands with us, not behind a window of perspective. The body occupies the canvas like a relief on the wall. That shallowness, typical of Matisse’s portraits of the period, allows color intervals to dominate without being sacrificed to vanishing points. It also amplifies the psychological effect: the viewer shares Margot’s air and light.

Material Presence and the Sense of Weather

Because the paint remains materially present, the portrait suggests a particular weather. The pale sky is thinly brushed, the sea a smooth horizontal, the scarf’s green dragged with a pressure that implies wind and weight. The hat’s interior shadow is heavy, as if the felt itself absorbs light. These cues give the portrait an outdoor clarity that many studio portraits lack. We are not told the time of day, but we feel it—the high, reflective brightness of seaside noon or late afternoon.

How to Look So the Picture Opens

Enter at the hands, where ocher and blue interlock. Follow the scarf up and feel how its greens alternate cool and warm until they meet the brim. Pause at the brim’s underside where a small ocher wedge kisses the cheek; that tiny harmony accounts for the entire lighting scheme. Slide to the eye and notice how little pigment is used to place the pupil and build the lid. Drift across the sea’s blue line and back into the dress, where repeated dark dashes create a rhythm that steadies the lower half. After a few circuits, the portrait stops looking like separate parts and reads as a single, balanced chord.

Meaning Beyond Description

“Margot” embodies a principle Matisse prized: painting as an instrument of calm intensity. By stripping away accessory detail and allowing color to do the work of structure, he conjures a presence that is luminous but not loud, poised but not inert. This is not a psychological novel in oil; it is a musical theme arranged for a few instruments—orange, green, blue, and pale air—played with confidence and restraint. The picture feels inevitable, as if these were the only possible colors that could hold this person in this light.

What “Margot” Contributes to Matisse’s Arc

The portrait confirms that Fauvist color could generate convincing likenesses without the safety net of academic modeling. It points forward to the Nice interiors, where figures and textiles share a common decorative logic, and further still to the paper cut-outs where color and contour fuse. In “Margot,” the ideas are already mature: volume is a function of temperature, edges are seams between hues, and the viewer’s eye completes what the brush wisely omits. More than a century later, the portrait remains modern because it trusts perception itself.

Conclusion: Presence Held Together by Color

“Margot” is a portrait composed like a song. The green hat lays down the melody, the blue dress provides a steady bass, the orange face carries the voice, and the pale air keeps the whole ensemble clear. The hands supply rhythm; the scarf, a graceful countermelody. Every stroke supports the central claim that color can build a human presence with clarity and tenderness. The painting does not demand attention; it earns it, holding the gaze as the sea behind it holds the horizon.