Image source: wikiart.org

A Portrait Built from Silence and Resolve

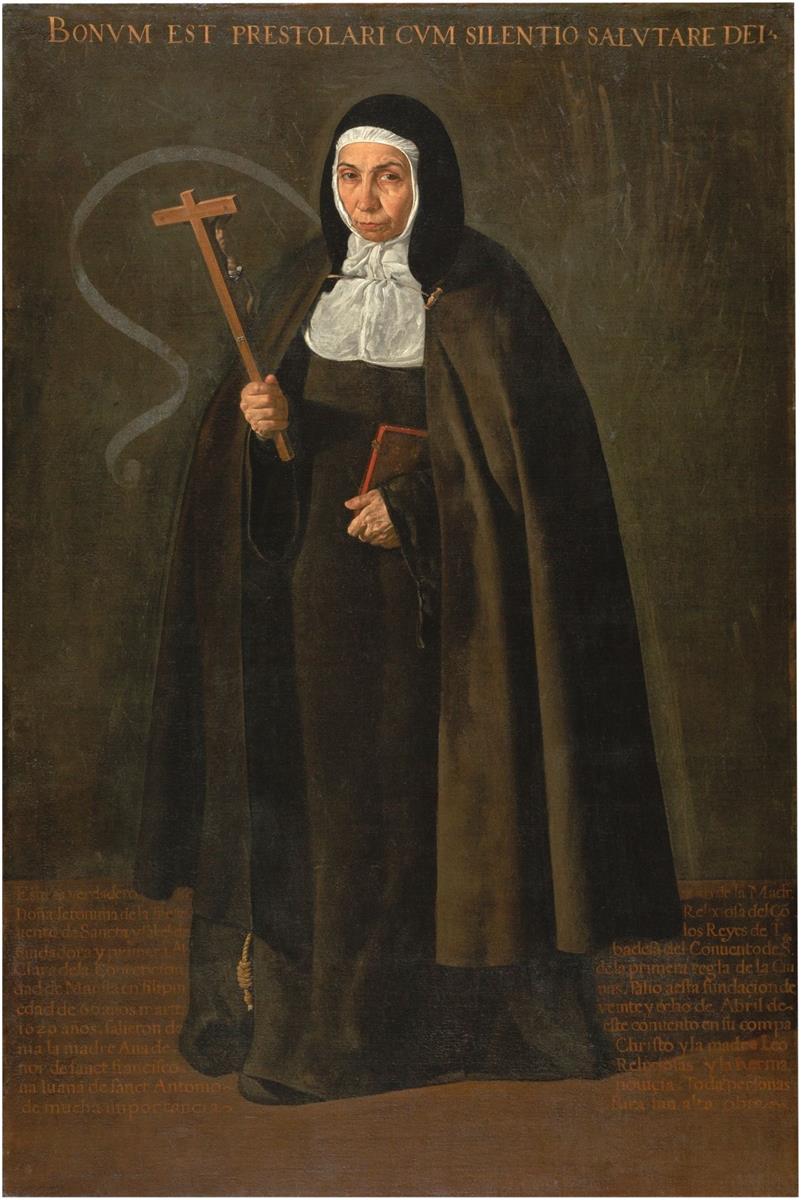

Diego Velázquez’s “Madre María Jerónima de la Fuente” stands like a column of steadiness in a dark room. The Franciscan nun is shown full-length, facing us without ornament, clothed in the sober browns of her order. In one hand she grips a wooden crucifix; in the other she holds a small book. A Latin inscription arcs across the top—“Bonum est prestolari cum silentio salutare Dei” (“It is good to wait in silence for the salvation of God”)—and further Spanish text gathers low at the sides, as if the painting itself is a document of witness. The figure is monumental yet human: the eyes steady and slightly reddened, the skin thin over bone, the mouth firm with a life of vows. Velázquez eliminates distraction so we can see what authority looks like when it is earned by humility.

Composition That Reads Like a Vow

The design is almost architectural. Madre María’s habit forms a massive, gently flaring triangle that anchors the entire canvas. The outer cape falls as a continuous plane of near-black, broken only by the luminous triangle of the white wimple and the pale face it frames. The crucifix lifts diagonally, a line of assertion held close to the body; the book is pressed against the chest at a slight angle, a private resource kept near the heart. The background is an austere field—nothing to divert attention but a faint serpentine flourish, like a ghostly S, that curves beside the nun, and the blocks of inscription near the floor. The space is shallow, the figure close. It feels like we are standing within arm’s length of a woman who will not waste either her time or ours.

Light as a Measure of Discipline

Illumination falls from the left, traveling across linen and face before decaying into the soft void of the background. Velázquez uses tenebrism, but not for theatrical shock. The light is measured, like the rule of life the portrait celebrates. The high white planes of the wimple and neck cloth are modeled with cool blues and pearly grays; the folds are crisp where attention is needed and soften where fabric recedes. On the face, the same light finds human topographies—the short notch above the upper lip, the tightness of skin at the eyelids, the faint flush along the nose and cheeks. The habit absorbs illumination quickly, shedding gleams only along edges and raised seams. Light here behaves like vocation: it clarifies essentials and ignores display.

A Face That Commands Without Asking

Madre María’s expression holds the picture. Her gaze meets ours without aggression, as if measuring whether we are prepared to hear what she has to say. The lips are set, neither dour nor kind; the eyebrows draw slightly together in a habit of focus; and the eyes’ reddened rims tell us about age and prayer as effectively as any anecdote. This is not a generalized “saintly” mask. It is a person rendered with the same unflinching truth Velázquez brought to watersellers, cooks, and kings. The authority that radiates from her is not bestowed by position alone; it is accrued by the discipline that has shaped face, posture, and the very way the hand closes around the crucifix.

The Crucifix and the Book: Two Tools, One Life

Velázquez gives the crucifix and the small volume equal dignity. The cross is plain, the kind of object a Franciscan would carry: light wood, straight grain, no metal ornament. He paints it as he would a spoon or a viol—accurately, without piety becoming fussiness. The book’s leather, edges, and small clasp catch spare highlights; the object reads as used rather than precious. Together, cross and text summarize the portrait’s theology: contemplation and action knit into one habit of mind, word and sacrifice carried into every room.

Inscriptions That Turn the Portrait into a Document

Unlike many of Velázquez’s early works, this canvas speaks with letters on its surface. The Latin motto across the top teaches the picture’s mood. The Spanish notes near the bottom identify Madre María and record context—her role in the foundation of a convent; the dates of journeys; the purpose of her mission. Velázquez integrates this text with the design rather than letting it float like a caption. The coppery letters are low in chroma and nestle into the dark ground, asserting meaning without disturbing the gravity of the image. The portrait thus becomes a public record and a private likeness at once: a face attached to a history.

Habit and Drapery as Architecture of Character

The habit is a marvel of controlled painting. The outer cloak falls in long, slightly concave planes; the inner robe creates a darker vertical seam that reads like a buttress; the hem grazes the floor where the coarse fabric meets the ground with weight. At the left hem a rosary cord peeks out—just enough to state the order, nothing more. In the small scalpel-cuts of light that mark hems and edges we sense Velázquez’s discipline: no decorative flourish, no theatrical breeze. The clothes are not costume but a dwelling, and the woman is at home within them.

The Latin Motto and the Portrait’s Inner Sound

“It is good to wait in silence for the salvation of God.” The words from Lamentations are a program for looking at this painting. Waiting and silence govern posture and palette; salvation becomes the light that gives purpose to the dark. Even the painter’s touch feels hushed: transitions on the face are feathered, not rubbed; the whites are clean but not glistening; the browns are varied into warm and cool so that the habit breathes without speaking loudly. Velázquez practices the motto in paint, turning restraint into eloquence.

Sevillian Realism Meets Counter-Reformation Purpose

Seville around 1620 demanded religious images that were clear, edifying, and morally persuasive. Velázquez supplies clarity—not through emblem piles or auroras—but through verisimilitude sharpened by wisdom. The nun stands as she would stand for a community: composed, ready, emblematic of a rule of life that declared poverty, chastity, and obedience as ways to freedom. The portrait honors the Counter-Reformation aim of making faith visible in faces and habits while refusing to flatten the subject into a stereotype.

Presence Without Pageantry

Many Spanish portraits of religious subjects indulge displays of lace, jewels, or heraldry. Velázquez pares all that away. The only decorative energy belongs to the brush itself where it pinches a fold or flicks a highlight. Everything else is service. The effect is paradoxical: the less the painting decorates, the more it dignifies. The artist trusts the human form, the human stance, and the human gaze to bear meaning.

An Anatomy of Hands That Have Worked and Prayed

Hands tell truth. The left hand clasps the book with fingers curled and tendons alive, a grip secure but not tense. The right hand supports the crucifix with plain competence—thumb squared, joint knuckles showing, a small glitter along the nail. These are neither delicate aristocratic hands nor monumentalized saint-hands; they are faithful instruments molded by years of habit. Their realism pulls the viewer out of pious distance and into recognition: this could be the hand that tended a sick sister, wrote a rule, or opened a door to the poor.

The Background as a Field of Silence

The ground is not simple black. It is a mixture of warm and cool browns, olive shadows, and hints of thinning glaze where the painting’s breath becomes audible. Within that field the faint S-curve, like a disciplined flourish of chalk, arcs behind the figure. We might read it as a symbol, a staff, an initial, or a painter’s quiet arabesque etched into a wall. Whatever its source, it animates the void just enough to keep the eye moving without disturbing the sternness of the scene.

Perspective at the Floorline: A Human Room

Velázquez grounds the figure with a simple plane: a floor of warm brown that tilts slightly, catches the hem’s shadow, and supplies the minimal spatial cue we need to feel the nun’s weight. The room itself is undefined; the air is chapel-calm. The portrait’s scale and vantage place the viewer at respectful proximity—near enough to feel addressed, not so near as to intrude. The measured distance matches the sitter’s authority.

Pigments, Surface, and the Craft of Restraint

The palette is as limited as a vow. Earth umbers and siennas build the habit; lead white and a touch of azurite-like cool produce the wimple’s planes; vermilion warms the inner eyelids and the edges of the book; a few discreet gold-brown glazes carry the inscriptions; black (or bone black) deepens recesses without chalking the paint. Brushwork is varied but unshowy: long, flat passes across the cloak; small, rounded touches on cheeks; knife-sharp edges along the crucifix and the book’s corners. The surface is coherent and matte, closer to the sheen of well-cared-for cloth than to the gloss of court portraiture.

A Life Placed Before a Community

The Spanish text at the base functions like a public pronouncement. Madre María is identified not only as a holy woman but as an actor in history: foundations made, journeys undertaken, dates recorded. Velázquez’s decision to include such text turns the canvas into a civic object as well as a devotional one. The community does not just honor a face; it remembers actions carried out in its name. The visual rhetoric—frontal, life-size, plain—suits that communal purpose.

Comparison with Velázquez’s Secular and Sacred Types

Put this portrait beside the waterseller, the old woman cooking eggs, or the Adoration of the Kings and you see the same ethic: attention as respect. Where the bodegones dignify labor, this portrait dignifies vocation. Where the Magi bow in wonder, this nun stands in resolve. The painter’s realism does not shift gears when the subject changes. That constancy is the secret of Velázquez’s authority: he never needs to exaggerate to persuade.

Emotion Contained, Meaning Amplified

The painting’s emotional register is safe inside its economy. There is pathos in the red rims of the eyes; there is tenderness in the slight incline of the head; there is even humor in the way the shoes hide under folds as if acknowledging human frailty. But feelings are contained within form. Because nothing is inflated, the meaning of the vow expands to fill the dark: patience, silence, and steadiness become luminous.

The Viewer as Addressee

The direct gaze invites a response. The object of that gaze is not a distant throne or an altar; it is us. We are asked, wordlessly, to consider what it would mean to wait in silence for what matters most. The crucifix and book are held not as props but as offerings: here are the instruments; what will you do with them? The portrait’s power lies in how quietly it asks that question.

Why the Image Still Works

In a culture saturated with spectacle, the picture’s refusal to entertain feels bracing. It proposes another kind of beauty—the beauty of integrity, of a life cohesive in aim and means. The limited palette becomes a virtue; the lack of setting becomes a space for encounter; the absence of ornament opens a path to the person. Velázquez gives us not a saint packaged for devotion but a human being whose faith has shaped her into an instrument of clarity.

Conclusion: Gravity with a Human Face

“Madre María Jerónima de la Fuente” is a manifesto of disciplined looking and moral seriousness. The figure stands, the room quiets, the light clarifies, and paint becomes a language of vow. Cross and book, habit and hand, inscription and gaze—all align to show what steadfastness looks like. The portrait is not loud, but it is unforgettable. It leaves the afterimage of a life gathered into purpose and offers, without rhetoric, the lesson of its motto: good is the waiting, and holy the silence in which salvation is met.