Image source: artvee.com

Historical Context: Munch’s Exploration of Love, Life, and Spirituality

When Edvard Munch created “Madonna” around 1894–1895, he was immersed in the defining project of his career: the Frieze of Life, a sprawling symbolic cycle exploring themes of love, anxiety, sexuality, and death. Fresh from the shockwaves generated by The Scream (1893), Munch relocated from Kristiania (now Oslo) to Berlin, where he encountered avant-garde circles and embraced printmaking as a medium for wider dissemination of his vision. In this period of intense psychological probing, Munch turned to the figure of the Madonna—a traditional symbol of purity and maternal grace—only to subvert it through his characteristic interplay of eroticism, spirituality, and dark foreboding. The result would become one of his most controversial and iconic images, a haunting portrayal that continues to captivate audiences over a century later.

Subject Matter: A Transgressive Vision of the Madonna

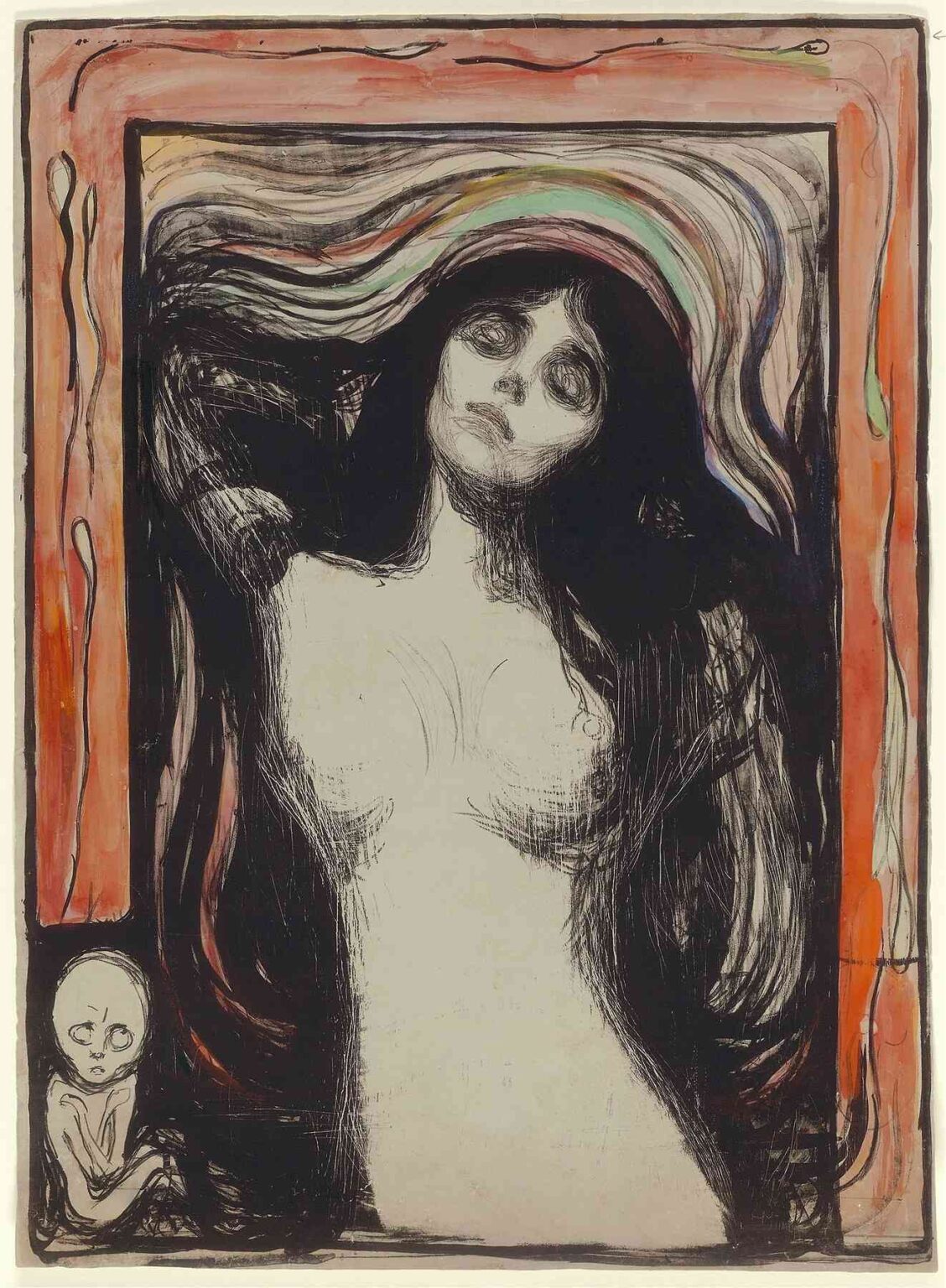

At first glance, “Madonna” might seem to depict a gently reclining female nude with flowing hair and closed eyes, framed by a halo-like arch. Yet beneath this surface lies a complex layering of meanings. The central figure, often identified as the Virgin Mary, is presented in a state of rapturous abandonment: her head falls back, mouth parted, and eyes shut as though in ecstasy or pain. Her sinuous hair cascades around her, dissolving into sinuous lines that blend with the background. Below her left hip, an androgynous, fetus-like figure crouches in an alcove, its oversized skull, hollow eyes, and emaciated body suggesting death or unborn life—an ambivalent companion to the Madonna’s sensual abandon. Through this juxtaposition, Munch entwines eroticism, motherhood, life’s beginning, and the specter of mortality.

Composition: Vertical Intimacy and Enclosing Halo

Munch structures “Madonna” in a tall vertical format, heightening the sense of intimacy between viewer and subject. The reclining body stretches from the lower half of the picture plane up to the center, where the figure’s shoulders and head press against a shallow, arching frame. This framing device, painted in pulsating reds and corals, functions like a halo or womb-shaped niche, enclosing the Madonna in a ritualistic sanctum. The swollen curves of her torso and the arch of her back mirror the arch above, reinforcing the unity of figure and frame. Meanwhile, the fetus-figure in the lower left corner is ensconced within its own sub-niche, creating a reciprocal relationship: mother and child, life and death, ecstasy and despair inhabit distinct yet interlocking spaces.

Palette and Color Symbolism: From Flesh Tones to Blood-Red Halo

Munch’s palette in “Madonna” is at once muted and electrifying. The Madonna’s skin is rendered in pale, almost translucent ivory, accented by soft touches of gray and violet to model her contours. Her dark midnight-black hair provides a bold counterpoint, its thick mass spilling around her and absorbing light. The background is restrained—subtle grays and whites evoke a neutral void—so that the most striking color remains the enclosing arch. Painted in sinuous washes of red, orange, and coral, this frame breathes with the warmth of flesh and the ductility of blood. Through layers of watercolor and tempera, Munch achieves a bleeding effect, as if the halo itself were alive, pulsing with the Madonna’s inner fervor. The minimal use of color elsewhere draws the eye inexorably to this arch, linking spirituality and corporeality in a single chromatic gesture.

Line, Form, and Expressive Mark-Making

Munch’s draftsmanship in “Madonna” melds precision with spontaneous gesture. The contour of the Madonna’s body is defined by a confident, unbroken line—her shoulder, waist, and thigh trace a single, graceful curve. In contrast, the hair and background lines are wild and swirling, scratched into the printing plate with feverish energy. These frenetic curls seem to pulse around her head, signifying both ecstasy and mental turbulence. The fetus-figure, drawn with thinner, more tentative lines, appears almost spectral, its forms emerging from negativity as though conjured by the Madonna’s own psyche. Across the plate, Munch varies line weight to articulate anatomical detail—soft shading around the breasts and abdomen—and to intensify emotional charge in areas like the arch’s rim and the hair’s eddies.

Printmaking Technique: Lithography and Hand-Coloring

“Madonna” exists in several impressions, often printed as a lithograph and subsequently enriched with watercolor, tempera, or pastel. Munch embraced lithography for its ability to retain the fluidity of drawing while allowing multiple reproductions. He drew the original stone with greasy crayon, carving into the image to create distinct planes of tone. After printing, he personally applied washes of color over selected impressions, making each hand-colored variant unique. The bleeding reds of the halo, the subtle modulations of flesh, and the smoky blacks of hair are all achieved by these added pigments. This hybrid process—part print, part painting—underscores Munch’s desire to merge reproducibility with the intimate touch of the artist’s hand, ensuring that each “Madonna” breathes with singular vitality.

Symbolism and Thematic Ambiguity

In Munch’s symbolic lexicon, “Madonna” is loaded with ambivalent signifiers. The traditional Christian associations of the Madonna as emblem of compassion and purity clash head-on with erotic and morbid undertones. Her ecstasy might be read as a divine rapture or a carnal surrender. The blood-red halo evokes both sanctity and menstruation—an intimate bodily process seldom acknowledged in religious iconography. The crouching fetus-figure may represent unborn life, evoking maternal longing, or the specter of death, echoing Munch’s fascination with mortality. This duality—life and death, holiness and flesh—is central to Munch’s Frieze of Life. In his view, the two were inseparable, the numinous and the corporeal entwined in the same human experience.

Relation to Munch’s Broader Oeuvre

“Madonna” stands alongside key works such as Puberty and The Kiss in Munch’s exploration of erotic psychology. However, it is unique in its conflation of maternal imagery with existential dread. By the late 1890s, Munch had transformed his personal traumas—family deaths, mental illness—into universal allegories. In “Madonna,” he crystallizes these themes: the Madonna’s pose is both nurturing and entranced; the fetus-figure is both offspring and mourner. This piece foreshadows Munch’s later paintings of women and death, such as Death in the Sickroom, where he continues to probe the thin line between eroticism and dissolution. The work’s continuing resonance lies in its refusal to offer a stable interpretation—a hallmark of Munch’s most powerful images.

Critical Reception and Scandal

Upon its first exhibitions in Berlin and Kristiania, “Madonna” provoked shock and acclaim in equal measure. Conservative critics decried its erotic frankness and macabre overtones, while avant-garde circles hailed it as a radical fusion of Symbolist depth and psychological insight. Some viewers were unsettled by the apparent eroticism of a nude Mother Mary; others found the small crouching figure disturbing. Over time, the image became emblematic of Munch’s defiance of academic norms. It influenced Expressionist painters who saw in Munch’s melding of spirituality and sexuality a model for confronting taboo subjects. Today, “Madonna” is often cited in surveys of erotic iconography and the modern reinterpretation of religious motifs.

Provenance and Legacy

Many original hand-colored impressions of “Madonna” entered the collection of the Munch Museum in Oslo after the artist’s death. Others reside in major European and American institutions. Because each hand-tinted version varies—no two are exactly alike—collectors prize early, richly colored prints. The image’s legacy continues in contemporary art, literature, and film. Feminist scholars reference “Madonna” in discussions of the body’s sanctity and profanation, while psychoanalysts examine it as an archetype of maternal ambivalence. The work’s enduring popularity attests to its capacity to evoke conflicting emotions: awe, desire, and apprehension, all coexisting in a single emblematic vision.

Conclusion: A Masterpiece of Spiritual Eroticism and Psychological Depth

Edvard Munch’s “Madonna” transcends its medium—print enriched by watercolor—to become a metaphoric synthesis of life’s greatest paradoxes. Through dynamic composition, unsettling symbolism, and innovative technique, Munch invites viewers to confront the entwined realities of love and death, purity and passion. The image resists facile readings, continually provoking fresh insights into the human condition. More than a reinterpretation of a traditional religious subject, “Madonna” asserts the modern artist’s license to explore the shadows beneath sacred icons. As both a technical marvel and a psychological maelstrom, it remains one of Munch’s most profound and provocative achievements.