Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

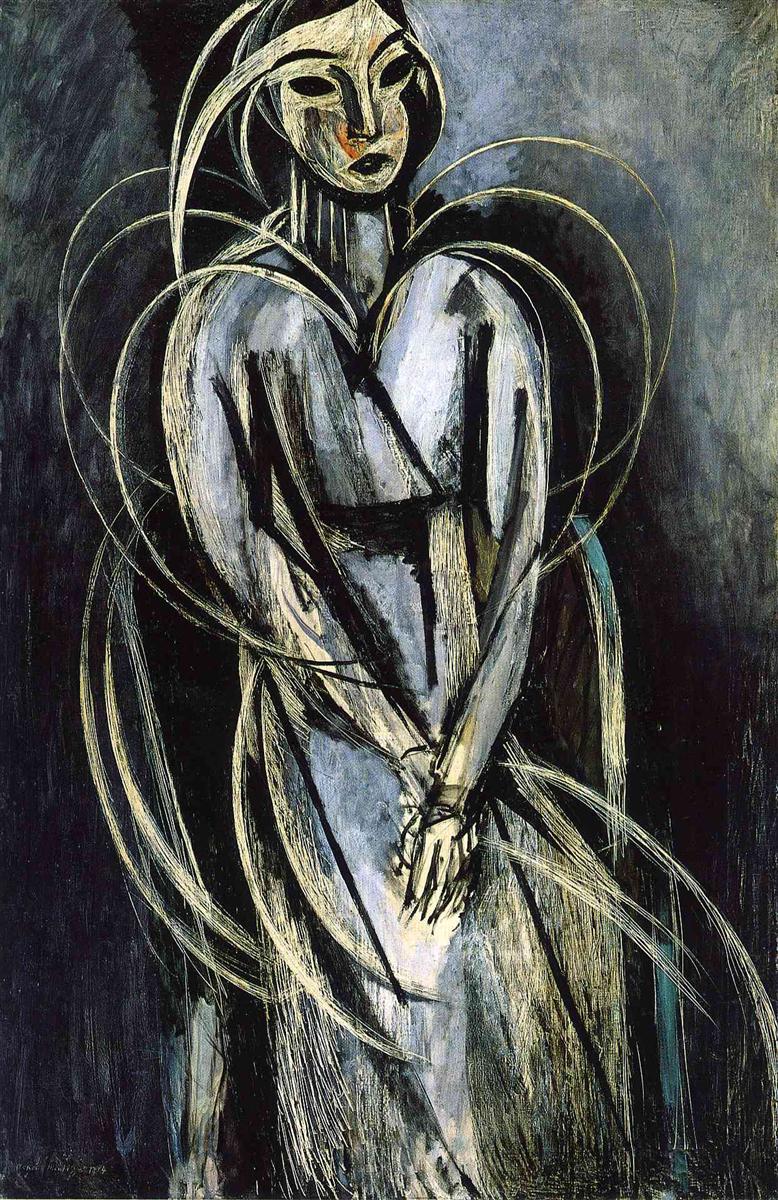

Henri Matisse’s “Madame Yvonne Landsberg” (1914) is a portrait that behaves like a storm of lines suddenly made still. The figure stands frontally, hands interlaced at the waist, her body defined by sweeping arcs of pale paint and emphatic vertical strokes that cut across a cool, nearly monochrome field. The head is masklike—eyes as almond slits, nose a firm wedge, mouth a compressed band—yet the presence feels urgent and human. Instead of the radiant color harmonies that made Matisse famous a decade earlier, this canvas relies on a limited range of blacks, whites, greys, and faint blues, with a breath of ochre at the face. It is as if the artist is asking how much life a portrait can carry when color is mostly withdrawn and drawing becomes action. The answer, in this painting, is: a great deal. “Madame Yvonne Landsberg” condenses the energy of gesture and the gravity of structure into a single charged image.

Historical Moment

The year 1914 was a hinge in Matisse’s career and in European history. Having returned from Morocco in 1912–13 with a renewed belief in large planes of color and simplified forms, Matisse spent the months before the First World War reducing his pictures to essentials. He explored a grisaille climate in interiors and portraits, tightened his contours, and built compositions from a few decisive elements rather than from sumptuous ornament. “Madame Yvonne Landsberg” belongs to this period of severe experiment. The sitter, a cultured patron and friend of the avant-garde, becomes the vehicle for a new pictorial language that prioritizes linear energy, shallow space, and sculptural presence over descriptive detail. The painting sits alongside other rigorous works from the same year—“French Window at Collioure,” “Woman on a High Stool,” “Gray Nude with Bracelet”—as a testament to Matisse’s desire to rebuild his art from the ground up.

First Impressions and Visual Walkthrough

Viewed from a distance, the portrait reads as an elongated figure set against a deep, cool field that drifts between midnight blue and soft graphite. The outline of the body is not strictly a contour but a cloud of arcs, like thrown ribbons that settle into an oval around the torso and skirt. Dark, vertical bars slash across the chest and limbs, anchoring the figure against the swirling atmosphere. The face, high and triangular, tips slightly left; its planes are sharply simplified and bounded by dark edges, so that light seems to radiate from within the mask rather than from outside illumination. Hands meet at the lower center, a knot of small strokes that contrasts with the broad sweeps elsewhere. Nothing in the background locates the sitter in a specific room. The portrait is not about furniture or fabric; it is about the rhythm of presence.

Composition as Tension and Release

Matisse organizes the picture as a balance between centrifugal and centripetal forces. The looping arcs curve outward from the figure, as if energy were streaming from the body in all directions. At the same time, a system of verticals and diagonals pulls the eye back to the core: thick dark strokes at the shoulders and chest, angled accents at the hips, a strong column of whites down the center of the skirt. This push-and-pull gives the image its breath. The arcs prevent the figure from feeling boxed in; the bars keep it from dissolving into atmosphere. The hands, small and clasped, serve as the compositional hinge—an island of gathered calm inside the storm.

The Palette and the Architecture of Value

The canvas is built from a limited palette in which value, not hue, does the expressive work. Blacks are used as structural beams that define features and joints; greys and cool blues interweave to describe volume and light. A few warm touches appear in the face and hands—subtle ochres that keep the portrait from becoming chilly. By withholding strong color, Matisse forces attention to fall on the relations of light and dark, thick and thin, soft and hard. The portrait becomes an orchestration of tonal chords: a luminous grey wedge at the sternum, a deep vertical down the abdomen, a veil of pale blue at the right shoulder. This architecture of value equips the figure with mass while preserving the painting’s essential flatness.

Line as Action

What first registers as outline soon reveals itself as action. Lines loop and sweep with the confidence of a calligrapher; some skid and fray, exposing the tooth of the canvas; others are dragged slowly so the bristles leave multiple parallel tracks. These lines do not merely describe the edges of forms—they generate them. The arcs at the shoulders read as hair, collar, and aura simultaneously. The repeated verticals across the torso act like ribs and also like structural ties that hold the composition together. In places the line doubles or triples, as if Matisse tried more than one path and kept them all, allowing the viewer to witness the sculpting of the figure in time. The drawing becomes a performance recorded in paint.

Space Without Depth

Despite the sense of volume in the body, there is little conventional depth. The background is a broad field of modulated darkness; the floor, wall, and furnishings are omitted. Space is a matter of overlap and value, not perspective. The arcs that surround the sitter glide in front of and behind the body by tonal shift alone; the head projects forward because its planes are sharper and lighter than the surrounding field. This shallow stage keeps the portrait aligned with Matisse’s decorative ideal, where the painting is an object with a designed surface rather than a window onto a distant room. The approach gives the image a poster-like clarity while leaving room for psychological nuance.

Mask, Face, and the Question of Identity

The face in “Madame Yvonne Landsberg” has the severity of a sculpted mask: the nose is a wedge, the eyes are elongate almonds, the mouth a compact line. Rather than diminishing individuality, the stylization intensifies the sitter’s presence. The mask reads not as concealment but as concentration. It relates to Matisse’s admiration for African and archaic sculpture, where clarity of plane and economy of detail convey authority without storytelling. The slight tilt of the head and the set of the mouth convey a mood that is neither decorative nor sentimental. This is a person presented through the essentials that endure after anecdote is removed.

Gesture, Body, and Poise

The clasped hands at the front communicate a poise that quiets the portrait’s surrounding velocity. Shoulders are high yet relaxed; the torso inclines a fraction left; the stance suggests patience rather than display. With almost no description of clothing, Matisse conveys weight and carriage by the direction of strokes and the accumulation of dark structural marks. The body is not anatomically itemized; it is mapped by energy. What could have read as a cage of lines instead reads as a living armature that holds the figure upright.

Process Made Visible

Everywhere the surface bears signs of revision. Around the head faint ghosts of earlier arcs remain; near the waist, alternate positions of lines are partially covered yet legible. The brushwork exposes layers—thin underpaints of cool grey-blue, overlaid by creamy whites and ink-like blacks. In places the paint is scraped or dragged so that the undercolor breaks through, keeping the field lively. The portrait thus reads as a record of decisions rather than as a fixed, polished likeness. Its vitality comes from the feeling that the image has been argued into being.

Dialogues with Fauvism, Cubism, and Expressionism

The painting stands in dialogue with the major currents of its time without submitting to any one of them. From Fauvism it retains the conviction that form may be stated with broad, unmodulated areas; however, color is deliberately restrained. From Cubism it borrows the emphasis on planar organization and the refusal of deep space, yet it does not fracture the figure into facets. From Expressionism it takes the power of the charged line and the idea that the surface can register emotion directly, but it avoids the theatrical distortion associated with angst. Matisse chooses a third way: clarity as intensity, economy as force.

Comparisons Within Matisse’s 1913–1914 Suite

Seen beside “Woman on a High Stool,” this portrait replaces that work’s architectural interior with a pure field; space is reduced so that line can carry the drama. Compared with “Gray Nude with Bracelet,” it is more dynamic and outwardly energized, trading that painting’s sculptural stillness for a web of motion. In relation to “French Window at Collioure,” it shows how the same discipline that stripped a window to three planes and a diagonal can be applied to a human figure without loss of humanity. These works, taken together, map Matisse’s search for a language that is both rigorous and alive.

The Modern Decorative Ideal

Matisse often spoke of a painting as an arrangement of surfaces designed to provide balance and serenity. “Madame Yvonne Landsberg” honors that ideal while expanding its expressive range. The swirling arcs function as ornamental rhythms, yet they are integral to the figure’s construction. The dark and light planes behave like inlaid pieces that, when properly proportioned, create harmony. The portrait could live on a wall with the dignity of a panel or textile, yet it never feels merely decorative. Its order is the order of a living presence achieved through designed relations.

Psychological Climate

The portrait’s cool palette and masklike face might suggest distance, but the total effect is one of attentive presence. The sitter’s eyes—reduced to long, dark shapes—are open and steady. The small ochre warm at the nose and lips, almost the only warmth in the picture, draws the viewer into the zone of breath and speech. The clasped hands suggest concentration without anxiety. The arcs that encircle the figure lend an aura, as if thought or music hovered in the air. The mood is not narrative; it is a climate of composure within energy.

Influence of Sculpture and Future Echoes

Matisse’s sculptural practice is legible in the painting’s reliance on simplified mass and structural lines that read like incised grooves. The figure feels carved out of the field, its planes turning with a few emphatic marks. Decades later, the arcs and cut-out logic seen here would reappear in the paper cut-outs of the 1940s, where figure and ground are built from sweeping shapes and bold edges. “Madame Yvonne Landsberg” thus anticipates the late work by proving that clarity of outline and the orchestration of few tones can carry intense expression.

How to Look

The canvas rewards alternating distance and proximity. From across the room, register the compositional backbone: the tall oval of arcs, the vertical strikes across the torso, the luminous wedge down the center. Step closer and follow a single arc from shoulder to hem, noticing how the pressure of the brush changes and how the line sometimes splinters into parallel hairs. Study the head’s planes—the sudden shift from dark to light at the cheek, the firm border of the eye slit. Attend to the small interlaced hands and the way lighter paint flickers at the knuckles. Step back again and let the portrait reassemble as a single, breathing figure. The act of looking becomes a slow reconstruction of Matisse’s decisions.

Legacy and Relevance

“Madame Yvonne Landsberg” has remained a touchstone for painters seeking an alternative to both descriptive realism and pure abstraction. It suggests that a figure can be simultaneously emblematic and individual, stable and kinetic. The painting’s reduced palette provides a model for how to use value to orchestrate a complex image; its linework demonstrates how drawing can be a mode of thinking rather than merely outlining. In contemporary terms, the canvas offers a lesson in disciplined economy: choose a few means and tune them until they sing.

Conclusion

In “Madame Yvonne Landsberg,” Henri Matisse builds a portrait from arcs, bars, and a narrow range of greys and blues—and in doing so captures a presence that feels unmistakably alive. Color retreats so that value and line can carry the force of attention. Space is shallow so that the surface can act like a stage for gesture. The face is masklike yet attentive; the hands gather composure at the center; the entire figure is held upright by a scaffold of strokes that register the artist’s searching hand. More than a century later, the painting still looks new because it embodies a durable truth about modern art: clarity can be as intense as complexity, and restraint can generate its own radiance.