Image source: wikiart.org

A Fauvist Path Lined With Light

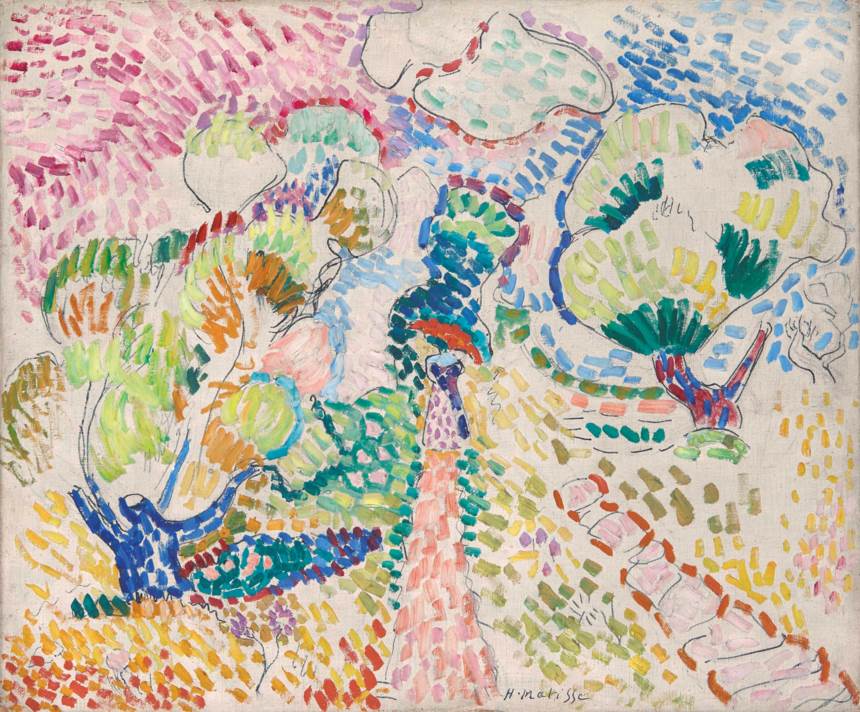

“Madame Matisse in the Olive Grove” was painted in 1905, the incandescent summer when Henri Matisse crystallized the language that critics would call Fauvism. The picture places a lone figure—Amélie Matisse—at the heart of an orchard, walking beneath a rainbowed parasol along a pale pink path that splits the canvas. Everything around her is made of short, buoyant strokes of unblended color. The sky is built from commas of lilac and blue; the foliage is a confetti of citron, emerald, and orange; the ground flickers in yellows and ochres. Much of the primed canvas remains unpainted, so that light seems to rise from within. Instead of describing a grove as a fixed place, Matisse constructs a field of sensations and invites the viewer to promenade through color itself.

1905 And The Invention Of A New Grammar

The year 1905 is the hinge of Matisse’s career. Working in Collioure with André Derain, he turned from the calibrated, optical mixtures of Neo-Impressionism to a looser, more declarative use of pure pigment. Rather than coax color to mimic nature, he let color become nature’s syntax on the canvas. This painting sits squarely in that moment. Its broken marks nod to Seurat and Signac, yet Matisse refuses their scientific regularity. He uses the division of color not as a rule but as an instrument, free to improvise the notes that best convey heat, glare, and breeze. The subject—his wife strolling—anchors the picture in modern life while granting him the freedom to turn a simple walk into a manifesto for painting.

Composition As Choreography

The composition reads like a dance taught to the eye. A vertical path climbs from the bottom center, tapering toward the middle where Madame Matisse stands. A secondary, curved path sweeps up the right edge in stepping-stone rectangles of warm color. Two large olive trees, one left and one right, act as sentinels that frame the stage. Between them, a constellation of smaller leaf-masses and sky-patches tilts in diagonals that nudge the gaze forward. The figure with the parasol sits just above the lower third, a quiet pivot around which the chromatic movement spins. There is perspective, but it is suggested by rhythm and interval rather than by strict geometry, so the feeling is of advancing through air that sparkles.

Drawing With Color Instead Of Line

Look closely and you see almost no conventional contour. Forms are defined where one swarm of strokes meets another. Blue and green dashes thicken along the edges of the trees to become a kind of outline, recalling the cloisonné borders admired by Matisse in Gauguin and in stained glass. The figure’s body is not encircled; it coheres because the surrounding marks press into it from every side. In this way drawing happens through color pressure, not graphite. It is a decisive step away from the nineteenth-century hierarchy that placed line above tone. Here, hue is the author of structure.

The Central Figure And The Human Scale

Amélie Matisse occupies only a small fraction of the painting, yet her presence calibrates everything. The parasol’s warm arc rhymes with the round canopies of the olives, and her violet-blue dress harmonizes with the cools of the sky while standing against the warm ground. She is a measure, not a portrait likeness. Her quiet stride and upright posture give the scene a tempo of measured leisure. Because the figure is simplified to a few emphatic notes, she becomes both an individual—the painter’s wife—and a stand-in for any viewer entering the landscape. The painting’s intimacy comes from this dual identity.

Color As Architecture And Weather

Matisse builds the picture from complementary chords. Blue sits against orange, green against red, purple against yellow, and each opposition energizes the other. Olive crowns mix spring greens with mustard yellows and sudden oranges, then are cinched by cooler blue dashes that make them pop forward. The sky floats in loose cloud-shapes of mauve and pale blue punctuated by untouched white, a device that reads as glints of blazing sun. The ground is not earth brown but a quilt of yellows and ochres touched with rose. The total effect is meteorological: you feel temperature and brightness, not just see them. Color functions simultaneously as architecture, atmosphere, and mood.

The Productive Role Of The White Ground

A hallmark of this canvas is its generous use of reserve. Matisse allows the primed fabric to show through between strokes so that light seems to pass through color rather than bounce off a solid skin of paint. Those open intervals keep mixtures clean, prevent the palette from becoming muddy, and activate the whole surface like paper breathing around watercolor. In bright Mediterranean conditions, glare is part of experience, and the bare ground acts as that glare, flashing between marks and heightening the immediacy of the scene.

Brushwork, Speed, And Control

Although the strokes look spontaneous, their distribution is carefully judged. In the left half, dense clusters of warm dabs press forward; in the right, cooler strokes thin out toward the sky, letting space open. The pinks of the central path are stacked in longer, brick-like dashes that distinguish it from the surrounding fields of point-like marks, so the viewer reads it as a plane one can walk upon. Around the figure Matisse tightens the pattern, increasing visual energy where attention should peak, then loosens it toward the edges to keep the eye circulating. Control lives inside freedom.

Between Neo-Impressionism And Fauvism

The painting sits at a crucial junction between two movements. The broken touch clearly remembers Pointillism, yet Matisse resists its optical discipline. He does not select only spectral primaries or calculate mixtures by scientific rule. He chooses hues for their expressive power, then spaces them by instinct to create a living vibration. Where Seurat often sublimated the painter’s hand to a system, Matisse foregrounds hand, choice, and speed. That difference—art as lived sensation rather than optical science—is one reason the painting still feels contemporary.

Olive Trees As Motif And Metaphor

The olive tree is both emblem and excuse. Its twisted trunks and tufted crowns invite expressive deformation; its cultural associations with longevity, sustenance, and southern light give the scene a rooted identity. Matisse exaggerates the elasticity of the branches until they read almost like human gestures, the left tree flinging an arm upward, the right bending warmly toward the figure. The orchard becomes a company of living forms greeting a visitor, and the visitor returns the greeting by joining their rhythm.

Leisure, Modernity, And The Feminine

Choosing Madame Matisse as the protagonist matters. In 1905 the artist also painted “Woman with a Hat,” a radically colored portrait of Amélie that scandalized Paris. Here she appears in the open air, relaxed yet composed, a modern woman claiming time for pleasure and walking. The parasol is both a practical prop and a sign of leisure. The painting thereby aligns a new vision of color with a new social experience: the freedom to move, to observe, and to savor environment without instrumental purpose. The feminine presence softens the avant-garde charge, making the radicality of the palette feel hospitable rather than aggressive.

Space, Scale, And The Feeling Of Nearness

Traditional perspective is reduced to a few cues: the tapering path, the smaller scale of trees as they recede, the overlap of foliage. Most of the depth comes from color temperature—warms advancing, cools receding—and from the density of marks. Because the figure is modest in size and the strokes around her are small and close, we feel near to her, as if we are following just a few steps behind. The canvas thus builds an ethical proximity: the viewer walks with, not merely looks at, Madame Matisse.

Drawing Out Of Memory And Observation

Works from Collioure often mixed on-site observation with studio re-composition. The dappled structure here suggests an artist working quickly in strong light, while the poised framing and the counterpoise of warm and cool trees hint at decisions refined away from the motif. The painting reads as a distilled recollection of the grove rather than a topographical report. What endured for Matisse was not the contour of each branch but the orchestration of feeling—where heat gathered, where air cooled, how sun broke into patterns.

The Music Of Strokes

The surface is musical. Each patch functions like a note with duration and timbre. Shorter, high-key marks are bright staccato; elongated strokes along the path are legato measures that carry the eye forward. Clusters beat like measures, and changes in direction feel like variations. The right-hand stepping-stones are a playful counter-melody to the steady vertical of the central path. By reading the painting musically, one understands its strange clarity: there is a score behind the color, and the viewer performs it in time.

Influence And Dialogue With Peers

Matisse’s summer alongside Derain produced close dialogues, and this canvas participates in that exchange. Derain’s landscapes of 1905 share the hot-cold pairing and the brash contour, but Matisse’s touch is lighter, his intervals airier, his sense of reserve more insistent. The memory of Signac remains, yet Matisse refuses the crystalline finish that often closes a Neo-Impressionist surface. He wants air in the weave. He also remembers the decorative flats of the Nabis and the black-edged color of Gauguin, translating those graphic lessons into an outdoor register. The painting becomes a crossroads where several currents meet and are simplified into a single voice.

The Ethics Of Joy And Ease

Matisse famously hoped for an art that would be “a soothing, calming influence on the mind, something like a good armchair.” In this grove, calm does not cancel vitality. The palette is high and the tempo quick, yet the experience is unstrained. Joy arrives not as spectacle but as clarity: each mark seems necessary, each color alive but not clamoring. Such ease is hard-won. It depends on leaving things out—the fussy details, the modeling shadows, the literal textures—so that what remains can breathe. The painting proposes that an ethics of joy is available to any viewer willing to trust sensation.

Anticipations Of Later Matisse

Several seeds planted here will bloom in later decades. The reliance on color to generate space leads to the radical interiors of 1908–1911 and ultimately to “The Red Studio,” where color becomes architecture outright. The simplified figure foreshadows the dancers and bathers, bodies reduced to rhythmic silhouettes. The practice of letting ground and mark collaborate reaches a culmination in the paper cut-outs, where color and contour are literally the same material. In retrospective light, the olive grove is a workshop in which Matisse rehearses the core moves of his future.

Why The Picture Still Feels New

More than a century later, “Madame Matisse in the Olive Grove” remains striking because it recalibrates what counts as accuracy. Instead of measuring likeness by contour, it measures truth by felt conditions—temperature, brilliance, air. Contemporary viewers, accustomed to images everywhere, recognize in this strategy an antidote to photographic literalism. The painting gives permission to trust what the body registers: that a hot day fractures vision into sparkles; that walking itself organizes perception; that color can be knowledge.

A Walk Toward Light

The last word belongs to the path. Its pinks lean warmer as they rise toward the figure, then cooler near the horizon where they meet the sky’s lilacs. The path is both real and metaphorical: a route through a grove and a route through painting’s future. To follow it is to accept color as guide. Madame Matisse leads, parasol tilted, steady and unhurried, and the viewer keeps pace, discovering that the grove is not only a place but a method—an arrangement of marks that produces clarity and pleasure.