Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

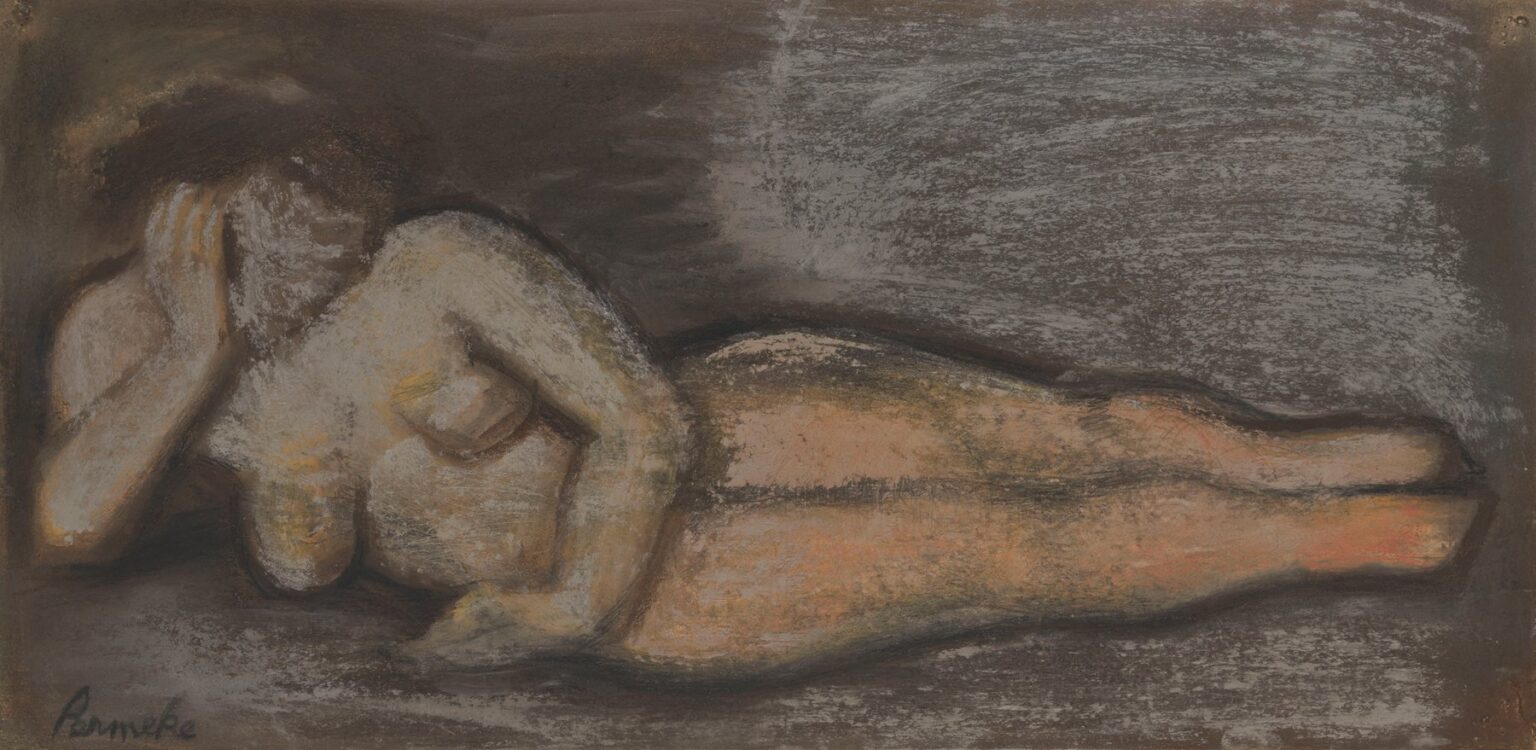

Constant Permeke’s “Lying Naked” (1942) presents a profound meditation on the human body, rendered with elemental force amid the turmoil of the Second World War. In this intimate pastel-on-paper study, the reclining nude emerges from a subdued, earthy ground as if shaped by both the artist’s hand and the weight of collective experience. Rather than a celebration of idealized beauty, Permeke offers a raw, unvarnished encounter with flesh and form. The figure’s pose—prone, contemplative, and partially concealed by her own arm—conveys vulnerability and introspection. This two-thousand-word analysis will explore the painting’s historical milieu, trace Permeke’s artistic trajectory up to 1942, and examine in detail its formal composition, chromatic harmonies, textural surfaces, and psychological resonance. We will situate “Lying Naked” within the artist’s broader oeuvre and consider its enduring legacy as a testament to human resilience in dark times.

Historical Context

In 1942, Europe was engulfed in conflict, with Belgium under Nazi occupation since 1940. The daily realities of rationing, censorship, and persecution formed a grim backdrop for creative expression. Many artists faced moral and practical dilemmas: whether to flee, to resist clandestinely, or to continue working under restrictive conditions. Permeke chose to remain in Belgium, retreating inward to explore the universality of the human form rather than overt political themes. “Lying Naked” emerges as a quiet act of defiance—privileging personal truth over propaganda. The stripped-down palette and the figure’s isolation echo the deprivation of wartime, yet they also underscore the enduring presence of the human body as a site of meaning. In a period when fabric and paper were scarce, the very act of drawing a nude embodied a reaffirmation of life, even as the world around the artist descended into chaos.

Artist Biography and Oeuvre to 1942

Born in 1886 in Antwerp and raised on a farm in Ostend, Constant Permeke first encountered the raw forces of nature in the rolling fields and churning sea of coastal Flanders. His early studies at the Antwerp Academy and a formative stint in Paris exposed him to emerging currents of Fauvism and Expressionism. By the 1920s, he had returned to Belgium as a leading proponent of Flemish Expressionism, celebrated for monumental depictions of fishermen, laborers, and rural life. The symmetry between the physical toil of his subjects and the tactile engagement of paint on canvas became a hallmark of his style. With the onset of World War II, Permeke’s focus shifted inward: large-scale compositions gave way to smaller, more introspective figural studies. “Lying Naked” marks a pivotal moment in this late phase. Here, the nude is not an academic exercise but a distillation of decades spent exploring the interplay of flesh, texture, and emotional gravity.

Formal Composition and Spatial Dynamics

At first glance, “Lying Naked” unfolds as a single horizontal plane: the nude figure reclines across the lower half of the sheet, her form echoing the panoramic sweep of the composition. Yet the arrangement is far from static. The subject’s torso twists subtly, her left knee raised and arm bent to shield her face, creating diagonal tensions that activate the horizontal expanse. The head, turned slightly away from the viewer, introduces a vertical counterpoint, while the interplay of bent and extended limbs forms an irregular polygon that both anchors the figure and invites the eye to roam. The background is deliberately ambiguous—a mottled field of umber and slate gray that suggests neither interior nor exterior space. This undefined setting allows the body to claim full attention, dissolving any narrative context in favor of pure, introspective presence. The absence of props or drapery further underscores the elemental relationship between figure and ground.

Color Palette and Tonal Harmony

Permeke’s palette in “Lying Naked” derives almost exclusively from the earth’s sediments: muted ochres, dusky umbers, and warm siennas dominate, punctuated by cool grays in shadowed recesses. The figure’s flesh is tinged with pale pink and soft ochre, applied in translucent layers that allow the raw paper to shimmer beneath. Highlights—concentrated along the curve of the hip and the ridge of the shoulder—are achieved by judiciously sparing pigment, revealing the paper’s ivory tone. Shadows deepen around the underside of the torso and the hollow of the back, where the artist’s heavier strokes pool into velvety darkness. This restrained chromatic scheme yields a cohesive tonal harmony: figure and background share the same chromatic family, blurring the boundary between flesh and earth. In the midst of wartime austerity, such a palette resonates as both a poetic conceit and a statement of material economy.

Light and Shadow

Light in “Lying Naked” is rendered with subtlety rather than drama. There is no single source; instead, illumination appears diffused, as if filtered through a cloudy sky or a shaded window. Soft gradations of midtone sweep across the body, defining contours without sharp contrasts. The gentle highlight on the thigh and the muted gleam along the shoulder line suggest an inner luminosity—an almost spiritual glow emanating from within the flesh. Shadows are built through repeated layers of pastel and charcoal, imparting depth but never harshness. The interplay of light and dark evokes a sense of calm introspection: the nude is neither basking in sunlight nor receding into total obscurity. Rather, she inhabits an in-between realm where form emerges from and returns to the darkness in a cycle of revelation and concealment.

Brushwork, Texture, and Materiality

Although executed in pastel and charcoal rather than oil, “Lying Naked” retains Permeke’s hallmark emphasis on materiality. Broad swaths of chalk create the figure’s core mass, while the addition of charcoal lines sharpens contours and defines anatomical transitions. In some areas, the pigment has been smudged and blended, imparting a soft, velveteen texture to the flesh. Elsewhere, the strokes remain visible—vertical striations on the thigh, feathery touches along the collarbone—that testify to the artist’s direct, hands-on engagement. The rough grain of the paper appears in places where the pigment is thin, adding a tactile depth that contrasts with the more heavily worked sections. This varied surface invites viewers to sense the weight and presence of both body and medium, reinforcing the notion that painting—or in this case drawing—is itself an act of embodied labor.

Anatomical Realism and Deviations

Permeke’s nude diverges from academic idealization in its embrace of naturalistic proportions and subtle imperfections. The torso is modestly curved, the breasts and belly bearing the gentle weight of gravity, and the limbs exhibiting a quiet tension where muscles contract or relax. The head is proportionally smaller, tilting away to suggest introspection rather than display. While classical nudes often emphasize ideal symmetry and flawless musculature, “Lying Naked” presents a body shaped by lived experience: the slight dip at the waist, the folds at the elbow, and the relaxed angle of the ankle all speak to the authenticity of human flesh. These deviations from canonical grammar imbue the figure with a profound candor, challenging viewers to recognize beauty in the ordinary and the partially concealed.

Symbolic Dimensions and Allegorical Readings

Beyond its corporeal presence, “Lying Naked” resonates with symbolic overtones. The protective gesture of the raised arm—shielding face and gaze—hints at themes of concealment and vulnerability. In wartime, such an instinct carries broader allegorical weight: the figure may stand for a generation striving to protect its inner self amid external threats. The reclining position has classical antecedents—Odalisques, Dead Christs, and mythological figures at rest—yet Permeke strips away narrative trappings to focus on existential stillness. The absence of accessories, clothing, or surrounding objects reduces the composition to a singular encounter between viewer and subject, body and earth. In this unadorned state, the nude becomes an archetype: a universal emblem of human fragility and the quiet dignity that endures even in darkness.

Emotional and Psychological Resonance

Although the figure lies in repose, there is a palpable emotional charge beneath the surface calm. The slight twist of the torso and the gentle tension in the bent knee suggest unease or watchfulness, as if the subject remains alert even in rest. The covered face amplifies this tension: it is both a gesture of retreat and an invitation to empathize with unspoken thoughts. Viewers are drawn into a shared space of contemplation, encouraged to sense the interior life that the painting both respects and preserves. In a time when public expression was fraught and dangerous, this private moment of introspection gains amplified significance. The work becomes less a portrait of a specific individual than a mirror for collective longing—for safety, for reflection, and for the simple act of being alive.

Position within Permeke’s Oeuvre

“Lying Naked” represents a crucial juncture in Permeke’s late career. In earlier decades, his canvases teemed with robust figures engaged in the elemental acts of labor—fishing nets hauled, fields plowed, storms weathered. By 1942, the scale had reduced and the focus intensified: a single body, stripped of context, embodies the distilled essence of his lifelong inquiries into flesh and earth. Compared with the ritualistic posture of his 1945 “Kneeling Nude,” the reclining figure here suggests respite rather than supplication. Yet both works share a commitment to unidealized realism, textured surfaces, and chromatic restraint. In the broader art-historical narrative, Permeke stands apart from contemporaries who embraced abstraction or surrealism in the war’s wake; his devotion to the corporeal offers a counterpoint that underscores the enduring power of the human figure to convey deep emotional truths.

Conservation, Reception, and Legacy

Following its creation, “Lying Naked” circulated in private exhibitions and gained recognition among Belgian art circles for its bold intimacy and material honesty. Conservationists note that pastel and charcoal on paper require careful environmental control—fluctuations in humidity threaten the delicate layers, and direct light can fade the chalk’s luminosity. Despite these challenges, the drawing has been preserved in major Flemish collections as a key example of wartime figural art. Modern scholars value it for its unflinching portrayal of vulnerability and its unique synthesis of Expressionist vigor with humanist introspection. In retrospective exhibitions, “Lying Naked” often features alongside works by artists who navigated the fraught terrain of occupation—its quiet power providing a poignant complement to more overt forms of resistance and documentation.

Cultural Significance of the Nude in Wartime

Permeke’s “Lying Naked” participates in a broader mid-century reconsideration of the nude as a vehicle for existential inquiry. While earlier traditions prized sensuality and mythological narrative, artists in the 1940s turned toward stripped-down realism to address questions of survival, identity, and memory. The nude became a cipher for resilience: the body, exposed and unprotected, yet undeniably present, bore witness to both atrocity and hope. In this context, Permeke’s drawing occupies a singular place: it neither glorifies martyrdom nor indulges in sentimental comfort. Instead, it offers a moment of quiet steadfastness, a pact between artist and viewer to acknowledge human fragility without surrender. Through this lens, “Lying Naked” transcends its material form to become a symbol of collective endurance and the enduring value of intimate, unembellished representation.

Conclusion

Constant Permeke’s “Lying Naked” (1942) stands as a masterful testament to the power of simplicity and material presence in art. Through a restrained palette of earth tones, textured pastel and charcoal surfaces, and an unidealized depiction of flesh, the drawing captures a moment of introspection and resilience against the backdrop of wartime hardship. The figure’s protective gesture, subtle anatomical deviations, and the diffuse interplay of light and shadow coalesce into a profound meditation on vulnerability, dignity, and the endurance of the human spirit. As both a late-career distillation of Permeke’s lifelong concerns and a poignant document of its era, “Lying Naked” continues to resonate with contemporary audiences, reminding us that even in our darkest hours, the body remains a vessel of meaning and hope.