Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

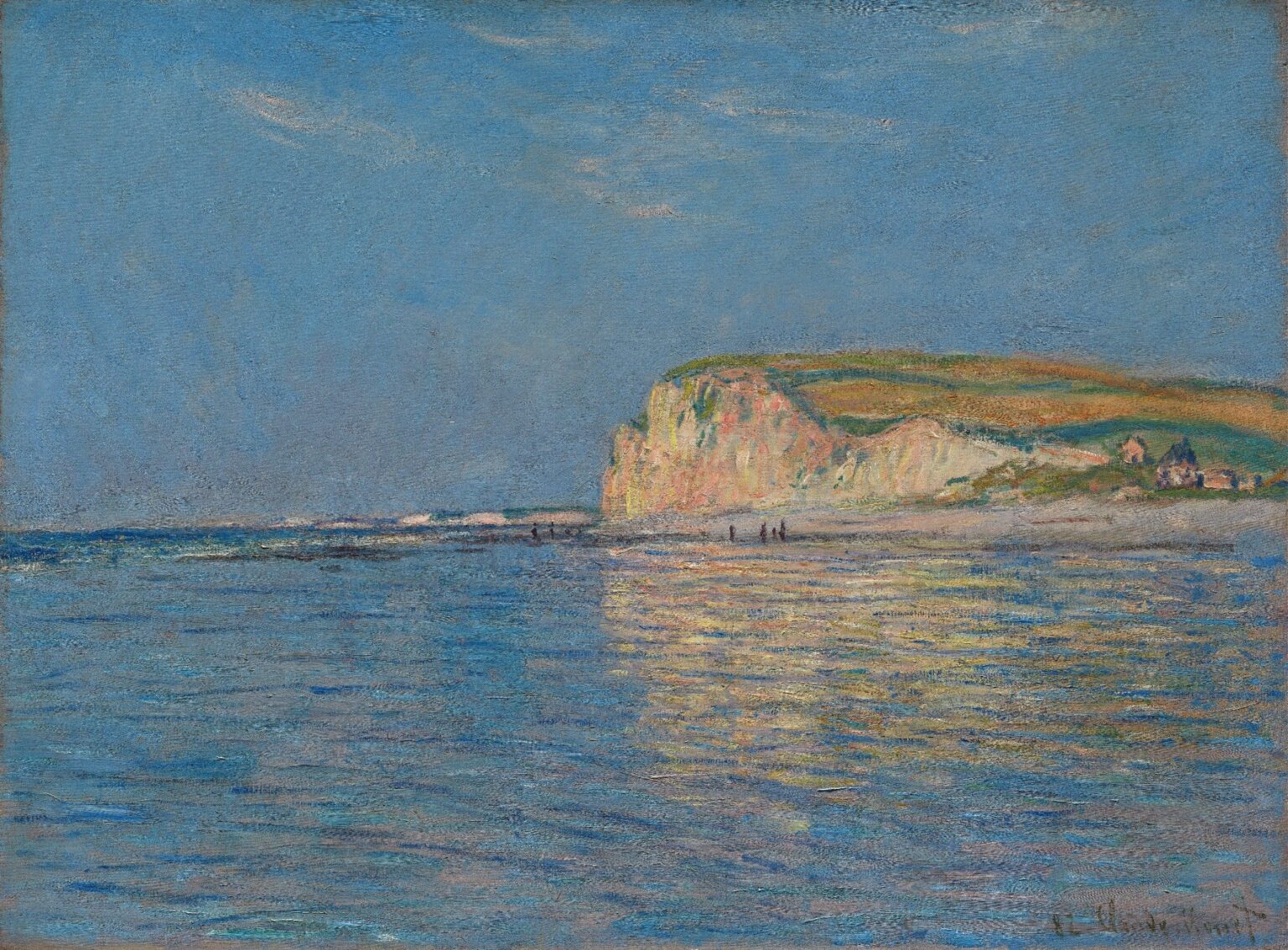

Low Tide at Pourville, near Dieppe (1882) stands as a luminous testament to Claude Monet’s mastery of coastal atmosphere and plein-air technique. In this painting, Monet captures the fleeting moment when the tide recedes along the Normandy shoreline, revealing a broad expanse of wet sand that mirrors the sky’s soft pastels. Through a harmonious interplay of light, color, and brushwork, the artist transforms a simple maritime scene into an immersive study of reflection, texture, and the ever-changing relationship between land and sea. This canvas invites viewers to share in the sensory experience of standing at the water’s edge, breathing in salt-tinged air, and witnessing nature’s subtle choreography.

Historical and Geographic Context

By 1882, Monet had firmly established himself as a leading figure of the Impressionist movement. Having exhibited with his peers in 1874, 1876, and 1877, he was renowned for landscapes that emphasized the effects of light over precise detail. Pourville-sur-Mer—a tucked-away fishing village near Dieppe—offered Monet fresh inspiration. Its chalk cliffs, wild flora, and shallow tidal flats provided ideal conditions for his plein-air explorations. The Normandy coast, with its rapidly shifting weather and clear, invigorating light, became a recurrent motif in Monet’s work. Low Tide at Pourville emerges from this fertile period of experimentation, when the artist sought to record the transient qualities of coastal environments under changing skies.

Monet’s Plein-Air Practice

Central to Low Tide at Pourville is Monet’s commitment to painting en plein air—working directly on location to capture instantaneous impressions. In 1882, he would have grappled with the challenges of outdoor painting: gusty sea breezes flapping his canvas, shifting sunlight that altered color values by the minute, and the ever-moving tides that reconfigured the beachfront. Rather than retreating to a studio for finish, Monet embraced these variables, applying paint quickly and confidently to preserve the moment’s authenticity. This on-site approach yields a canvas that resonates with immediacy, allowing viewers to feel the painting’s environmental conditions rather than merely observe them.

Composition and Perspective

Monet arranges Low Tide at Pourville around a sweeping horizontal axis that divides the work into two principal zones: the reflective tidal flats below and the expansive sky above. The horizon line sits low, accentuating the sky’s breadth and emphasizing the sea’s reflective qualities. In the foreground, irregular swaths of wet sand create a rhythmic pattern of light and shadow, leading the eye toward clusters of idle rowboats and figures near the water’s edge. The distant promontory of Dieppe’s cliffs anchors the midground, providing a structural counterpoint to the compositions’ fluid foreground and vast sky. Through this balanced schema, Monet achieves both spatial depth and compositional harmony.

Treatment of Light and Color

Light is the painting’s animating force. Monet employs a high-key palette of pale blues, soft grays, and subtle pinks to suggest the diffuse glow of an overcast afternoon. Patches of sunlight break through thin cloud cover, illuminating sections of the tidal flats in silvery highlights. These sparkles of reflected light are rendered with short, broken strokes of white and warm ochre, creating a shimmering effect that conveys both the sand’s dampness and the water’s sheen. The sky, built from layered washes of cerulean and cobalt mixed with touches of rose madder, suggests a gentle light suffusing the entire scene. Monet’s nuanced use of complementary colors—such as placing violet shadows beside warm yellow highlights—enhances the painting’s vibrancy and optical depth.

Brushwork and Surface Texture

Monet’s brushwork in Low Tide at Pourville varies in scale and direction to articulate different surfaces. In the wet sand, he uses broad, horizontal strokes that sweep across the canvas, mimicking the tidal movement. These strokes are interspersed with shorter, stippled marks that evoke puddles and the granular texture of sand. The rowboats and human figures are suggested through economical, vertical dabs—just enough to convey presence without interrupting the painting’s overall cohesion. The sky features fluid, diagonal sweeps that capture the movement of clouds. By retaining the individuality of each stroke, Monet allows the painting’s surface to become a tactile record of his hand’s journey across the scene.

Spatial Depth and Atmospheric Perspective

Depth in Low Tide at Pourville arises from Monet’s skillful use of atmospheric perspective. Foreground elements—the boats, figures, and sand patterns—are painted with greater contrast and vividness, drawing immediate attention. As the eye moves toward the cliffs of Dieppe, forms soften and colors cool, suggesting distance. The horizon, where sea meets sky, is rendered in delicate, almost misty tones, further reinforcing the sense of spatial recession. This graduated clarity mirrors human vision: near objects appear sharp, while distant forms blur into the atmosphere. Monet’s atmospheric layering invites viewers to traverse the painting’s scenic transition from tactile foreground to ethereal horizon.

Human Presence and Scale

While the natural elements dominate, Monet integrates subtle human touches to convey scale and narrative. A handful of figures—likely local fishermen or beachcombers—dot the middle ground, their dark silhouettes contrasting against the luminous tidal flats. Their small size relative to the expansive landscape underscores nature’s grandeur and the solitude of coastal life. Nearby, a cluster of inverted rowboats lies idle on the sand, hinting at human labor paused by the ebbing tide. These modest inclusions situate the painting within a lived environment, affirming Impressionism’s democratic ethos: everyday scenes and ordinary labor worthy of artistic attention.

Interaction of Land, Sea, and Sky

Monet’s painting celebrates the dynamic interplay among land, sea, and sky at low tide. The receding ocean exposes a broad, reflective plane that bridges earth and heaven. This interstitial zone, where water’s remnants mirror the sky, becomes the focal point of visual and atmospheric interaction. The cliffs on the right—bathed in soft light—stand as stoic witnesses to tidal rhythms, anchoring the composition’s ephemeral elements. Together, these components form a unified ecosystem: the sand and boats speak of human endeavor, the sea conveys fluidity and change, and the sky offers endless possibility. Monet’s canvas thus becomes an ode to the coastal environment’s cyclical dance.

Geological and Ecological Details

Monet’s portrayal of the beach’s geology and ecology is both accurate and evocative. The tidal flats, rendered in layered pigments, suggest sediment patterns and water channels carved by the receding tide. The rowboats imply sheltered coves suitable for fishing or transport. In the cliffs, striations of white chalk and weathered stone are hinted at through vertical and diagonal strokes of warm whites, ochres, and cool grays. Though Monet never provided botanical precision, his broken color mimics dune grasses and salt-tolerant flora clinging to cliffs and sandbanks. These subtle ecological cues reinforce the scene’s authenticity and Monet’s deep observational acuity.

Psychological Resonance and Mood

Low Tide at Pourville exudes a contemplative mood born of solitude and quiet observation. The muted palette and serene composition evoke a sense of calm and introspection, as if inviting viewers to pause and reflect on nature’s rhythms. The painting’s subdued light and misty horizon suggest introspective melancholy, tempered by the vitality of reflected sunlight. Monet’s focus on an everyday coastal moment—a lull between tides—offers a poetic meditation on impermanence and renewal, echoing broader Impressionist themes of capturing the ephemeral.

Monet’s Normandy Oeuvre

Monet’s Normandy paintings—from Étretat to Pourville and beyond—document his lifelong fascination with coastal landscapes. Compared to the monumental arches of Étretat or the wild vegetation of Bordighera, Low Tide at Pourville emphasizes the transient surfaces exposed by the tidal cycle. It occupies a unique place in Monet’s Normandy oeuvre, focusing on sand and reflection rather than cliffs or figures. This variation demonstrates Monet’s restless creativity: he returned repeatedly to familiar locales, finding endless novelties in light, weather, and tidal states.

Technical Studies and Conservation

Conservation analyses of Low Tide at Pourville have revealed Monet’s stratified painting process. Infrared reflectography uncovers an underdrawing mapping the horizon and rowboat positions, indicating compositional planning despite the painting’s spontaneous look. Pigment analysis identifies lead white, cadmium yellow, and viridian among Monet’s palette, applied in both thin glazes and thicker impasto. Microscopic cross-sections show that the tidal flats were built up in successive layers, enabling light to penetrate and reflect through the paint. Recent cleaning and varnish removal have restored the painting’s original brilliance, ensuring its delicate tonalities remain vivid.

Exhibition History and Critical Reception

First exhibited in the mid-1880s, Low Tide at Pourville received praise for its vibrant color harmonies and evocative atmosphere. Critics lauded Monet’s ability to transcend literal topography and capture the poetic essence of coastal light. Some detractors, accustomed to more polished finishes, found his brushwork too sketch-like. However, as Impressionism gained acceptance, the painting was recognized as a pioneering work in plein-air coastal studies. Over subsequent decades, it passed through prominent private collections before entering a major museum, where it continues to captivate audiences with its luminous portrayal of Normandy’s tidal landscape.

Influence and Legacy

Monet’s Low Tide at Pourville influenced both his contemporaries and later generations of artists committed to capturing natural phenomena. Impressionists such as Pissarro and Sisley drew inspiration from Monet’s integration of human figures within dynamic landscapes. In the 20th century, plein-air and colorist painters—from the Fauves to Abstract Expressionists—looked to Monet’s broken brushwork and optical color mixing as models for conveying sensation and mood. Today, Low Tide at Pourville remains a benchmark for coastal landscape painting, celebrated for its harmonious fusion of light, color, and the rhythms of the natural world.

Conclusion

Through Low Tide at Pourville, near Dieppe, Claude Monet elevates an ordinary tidal scene into a transcendent study of reflection, light, and atmospheric interplay. His expert plein-air technique, fluid brushwork, and nuanced palette capture the sensory essence of Normandy’s shoreline—its shifting sands, boats waiting for the tide, and the soft glow of overcast light. The painting endures as both a historical record of Impressionist innovation and a timeless invitation to contemplate nature’s beauty in its most fleeting moments. In standing before this canvas, viewers are transported to the water’s edge, where the world seems to pause in a delicate balance between land, sea, and sky.