Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

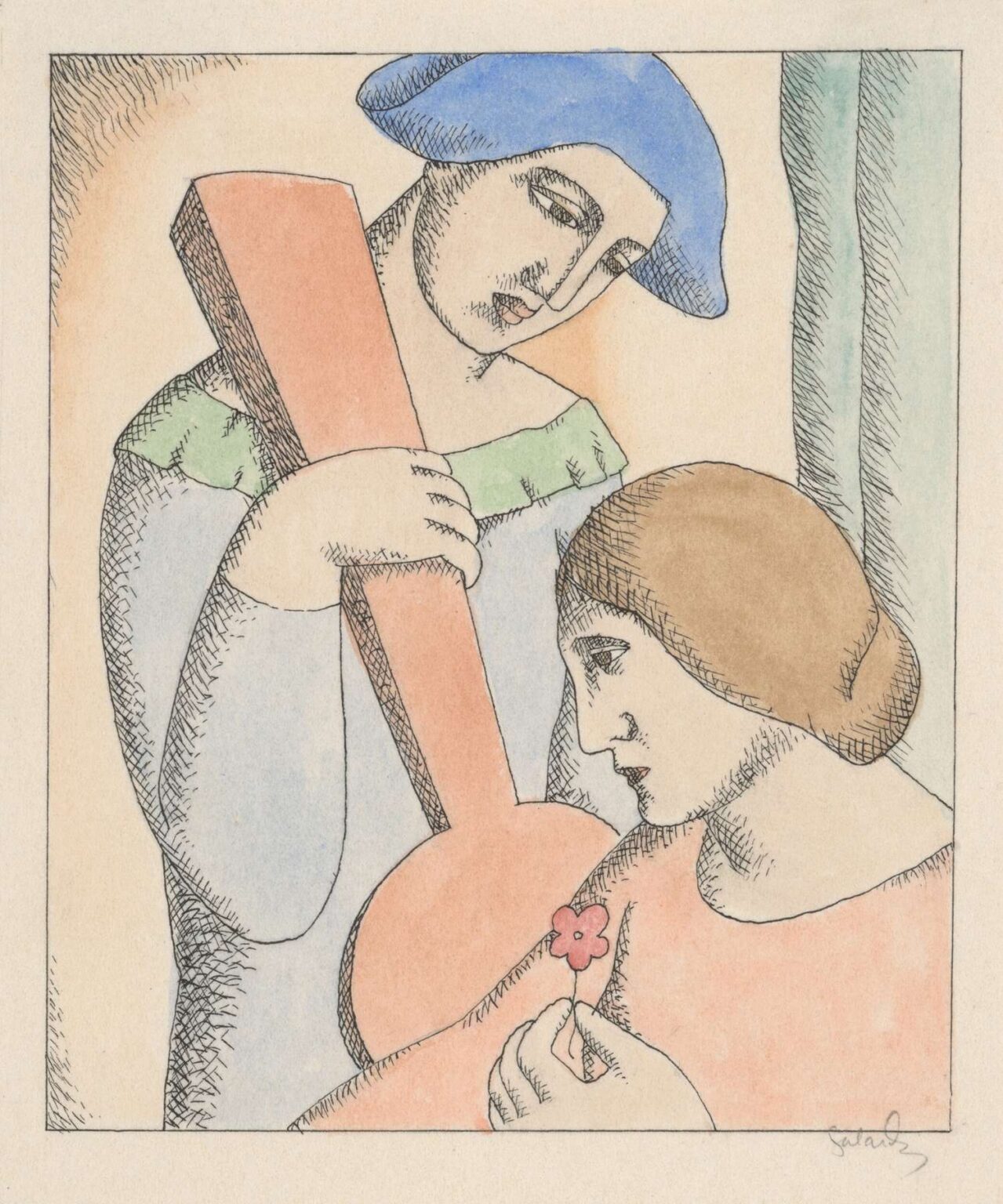

In Lovers Harlequin and Columbine (1928), Mikuláš Galanda captures the delicate interplay of affection and theatricality through a modernist lens that bridges folk tradition and avant‑garde innovation. At first glance, the painting presents two figures drawn from the commedia dell’arte—Harlequin, with his recognizable hat and lute, and Columbine, holding a small flower—but upon closer inspection, Galanda’s treatment transcends mere costumed characters. Through a subtle interplay of line, color, and composition, he transforms their interaction into a timeless celebration of love, longing, and the performative aspects of human relationships. This analysis will explore how Galanda’s work reflects his artistic evolution, the cultural significance of commedia dell’arte motifs in Central Europe, and the painting’s formal qualities—from brushstroke to palette—and how these elements coalesce into a deeply resonant portrait of two lovers on a metaphorical stage.

Historical Context

The late 1920s in Czechoslovakia were years of cultural effervescence and national self‑definition. Having achieved independence in 1918, the young republic welcomed a surge of artistic experimentation, with painters, writers, and performers seeking to forge a modern cultural identity rooted in local traditions. In Bratislava and Prague, artists engaged with European currents—Cubism, Expressionism, and Surrealism—while simultaneously drawing inspiration from Central Europe’s rich vernacular heritage. Commedia dell’arte characters, long familiar through folk theater traditions and itinerant performers, became powerful symbols of play, disguise, and social commentary. Against this backdrop, Galanda’s decision to depict Harlequin and Columbine in a tender embrace resonates both as an homage to popular spectacle and as a meditation on the masks we wear in private and public life.

Mikuláš Galanda’s Artistic Journey

Born in 1895, Mikuláš Galanda trained at the Hungarian Royal Academy in Budapest, where he mastered academic draftsmanship before venturing to Munich and Vienna. Influences from the Viennese Secession and early German Expressionism sparked his interest in bold contour and emotional depth. Returning to Bratislava in the 1920s, he co‑founded the Nová Trasa (New Path) group in 1928, advocating for art that was socially engaged, formally distilled, and accessible. Galanda’s early work featured richly colored easel paintings and folk‑inspired motifs, but by the mid‑1920s he had embraced graphic media—woodcut, lithography, pen‑and‑ink—and a leaner vocabulary of line and tone. In the period surrounding 1928, his style crystallized into a distinctive fusion of folk imagery and modernist reduction. Lovers Harlequin and Columbine emerges at this pivotal moment, showcasing Galanda’s mature approach to figuration, narrative, and symbolic layering.

Iconography of Commedia dell’Arte in Central Europe

Commedia dell’arte, the improvisational Italian theater tradition of masked archetypes, took root across Europe from the sixteenth century onward. Harlequin, the quick‑witted servant clad in a patchwork costume, and Columbine, the charming ingénue, became staples of popular performance. In Central Europe, itinerant troupes brought these figures to town squares and courtly entertainments alike. Their costumes and gestures entered vernacular art through prints, puppetry, and folk festivals, symbolizing both comedic relief and subtle social critique. For modernist artists like Galanda, these characters offered a rich symbolic lexicon: Harlequin’s multicolored attire spoke to the fractured self in the modern age, while Columbine’s grace embodied feminine allure and emotional sincerity. By pairing them in an intimate moment, Galanda tapped into deep cultural associations that his audience would readily understand.

Formal Composition and Design

Galanda’s composition in Lovers Harlequin and Columbine is carefully balanced yet dynamic. The two figures fill the picture plane, their bodies overlapping to create a sense of intimacy. Harlequin’s tilted head and downcast eyes guide the viewer’s gaze toward Columbine, whose profile is turned slightly away, as though caught in a private reverie. Harlequin’s lute—an oblong shape rendered in a contrasting color—serves as a vertical counterpoint to the diagonal sweep of his bent arm. Columbine’s small flower, delicately held between her fingers, introduces a circular motif that softens the composition’s angular tension. Galanda frames the scene within a near‑square border, evoking the stage proscenium of a theater, reinforcing the painting’s performative subtext while capturing an unguarded moment between lovers.

Line Work and Tonal Contrasts

Line is at the heart of Galanda’s method in this work. Each contour—be it the curve of Columbine’s cheek, the angle of Harlequin’s lute, or the drape of a sleeve—is delineated with precision yet retains a lively energy. Fine hatchings within the figures suggest volume and texture without resorting to fully modeled forms. The tonal contrasts between the inked lines and the soft watercolor washes create a subtle spatial depth: the figures stand forward against a pale ground, while hatched backgrounds hint at curtain folds or atmospheric space. The interplay between crisp contour and gentle tonal inflection reveals Galanda’s graphic sensibility, a credit to his background in printmaking, and ensures that the painting functions as both a drawn sketch and a colored composition.

Color Palette and its Symbolism

Galanda’s color choices in Lovers Harlequin and Columbine are at once limited and expressive. Harlequin’s cap, washed in a clear azure tone, signals both his playful spirit and the open sky of romantic possibility. The lute and the flower introduce warm terracotta and coral accents that bind the figures together emotionally. Columbine’s robe and Harlequin’s tunic receive diluted green and gray washes, evoking the muted tones of folk textiles. The restrained palette prevents the work from feeling decorative or overwrought; instead, it highlights the essential emotional notes—joy, tenderness, and longing. By employing watercolor and light gouache, Galanda allows the paper’s ivory ground to shine through, lending the scene an airy luminosity that underscores the ephemeral nature of love.

The Figures: Harlequin and Columbine

In Galanda’s portrayal, Harlequin and Columbine emerge as sympathetic, humanized figures rather than mere stock characters. Harlequin’s stylized features—his straight nose, gently curved lips, and dream‑like gaze—reveal a soul attuned to emotion. His hand rests lightly yet possessively on Columbine’s shoulder, indicating both affection and the delicate power dynamics of courtship. Columbine, with softly rounded cheeks and a contemplative expression, seems to withdraw into her own feeling, as though savoring a secret pleasure. Her hand, clutching a modest bloom, suggests that she recognizes love’s fragility. Through these careful characterizations, Galanda elevates the commedia dell’arte duo into universal archetypes of partnership—one playful and protective, the other tender and introspective.

Gesture, Gaze, and Emotional Expression

The emotional core of Lovers Harlequin and Columbine lies in its gestures and gazes. Harlequin’s head tilts toward Columbine in a protective arc; his downturned eyes convey quiet adoration. Columbine’s gaze is cast downward, perhaps shy or caught in a private moment of reflection. The placement of their hands—his on her shoulder, hers holding a flower—speaks volumes about the nature of their bond: balanced between giving and receiving, offering and cherishing. These gestures, stripped of extraneous detail, become the painting’s primary narrative mechanism. They invite viewers to participate in the lovers’ intimate exchange, to recall their own experiences of tenderness and longing.

Spatial Dynamics and Negative Space

Though the figures dominate the frame, Galanda employs negative space to heighten their presence. The background, defined by sparse hatchings and light tonal washes, recedes into near abstraction. This deliberate minimalism strips away any distracting elements—no stage props, no detailed scenery—focusing attention entirely on the lovers. The slight sense of a border or curtain implied by vertical strokes suggests the theatrical origins of the characters, yet its vagueness allows the viewer to shift seamlessly between stage and real life. In this way, negative space becomes both a literal absence of form and a metaphorical invitation to fill the void with personal imagination and emotional resonance.

Technical Execution and Medium

Lovers Harlequin and Columbine is executed in a combination of pen‑and‑ink and watercolor (or diluted gouache) on paper. The drawing began with precise ink contours, laid down with a fine nib that allowed for both sweeping curves and delicate hatchings. Subsequent washes of color were applied with a light touch, preserving the crispness of the linework while introducing subtle tonal variations. The watercolor’s translucency reveals the underlying ink and paper grain, contributing to a sense of material presence. Galanda’s deft control of brush and pen attests to his mastery of mixed media and his ability to synthesize graphic clarity with painterly warmth.

Relationship to Slovak Modernism

Within the burgeoning art scene of interwar Slovakia, Galanda’s Lovers Harlequin and Columbine occupies an important place in defining a modernist direction that was simultaneously local and international. By drawing on folk and theatrical sources familiar to Slovak audiences, he grounded his work in shared cultural reference points. By applying European avant‑garde techniques—reductive line, flat color planes, staged composition—he aligned Slovak art with broader modernist conversations. This blend of the vernacular and the contemporary epitomized the Nová Trasa ethos and influenced contemporaries and students who sought to balance national heritage with formal innovation.

Cultural and Symbolic Significance

The enduring appeal of Lovers Harlequin and Columbine rests in its capacity to speak across contexts. On one level, it celebrates the joy and complexity of romantic connection; on another, it alludes to the performative nature of identity, the masks we wear to navigate social roles. In the historical moment of the late 1920s, these themes resonated in a society negotiating tradition and modernity, certainty and change. Today, the painting’s symbolism remains potent: it reminds viewers that love is both a private intimacy and a public performance, a playful disguise and a sincere pledge. In this duality lies its power to engage successive generations.

Comparative Analysis with Contemporary Artists

Galanda’s approach in Lovers Harlequin and Columbine can be compared to the works of contemporaries such as Pablo Picasso’s rose‑period figures or Giorgio de Chirico’s metaphysical characters. Like Picasso, Galanda reduces form to essential curves and gestures, yet he retains a lyrical warmth absent from some cubist abstractions. Like de Chirico, he stages figures against sparse, ambiguous backgrounds, evoking dreamlike spaces, though Galanda maintains a folk‑inflected intimacy rather than de Chirico’s haunting ennui. In Central Europe, artists such as Emil Filla and Bohumil Kubišta explored similar intersections of figuration and abstraction; Galanda’s unique contribution lay in his integration of theatrical folklore with a modern graphic sensibility.

Reception and Legacy

Upon its first exhibition in Bratislava galleries, Lovers Harlequin and Columbine was praised for its elegant synthesis of folk motifs and modern form. Critics highlighted Galanda’s ability to evoke deep emotion through minimal means, praising the work’s refreshing departure from academic realism. The painting traveled to Prague and beyond, appearing in international surveys of modern art where it stood out for its poetic directness. In subsequent decades, it became a staple in retrospectives on Slovak interwar art, signifying the period’s humanistic turn within Modernism. Contemporary exhibitions continue to feature the work as emblematic of Galanda’s legacy: an artist who brought the stage of popular tradition into dialogue with the canvas of avant‑garde exploration.

Conclusion

Mikuláš Galanda’s Lovers Harlequin and Columbine (1928) remains a masterwork of modernist portraiture—deceptively simple in appearance, infinitely rich in emotional and cultural resonance. Through precise contour, a carefully calibrated palette, and an evocative composition free of extraneous detail, Galanda transforms two theatrical archetypes into universal symbols of love’s playfulness and depth. The painting’s fusion of folk tradition, theatrical iconography, and avant‑garde reduction exemplifies the spirit of Slovak Modernism, affirming the enduring power of cultural heritage when reimagined through a contemporary lens. As viewers revisit this tender scene, they discover anew the timeless truth that human connection, like a well‑worn mask, can both reveal and enchant the heart.