Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

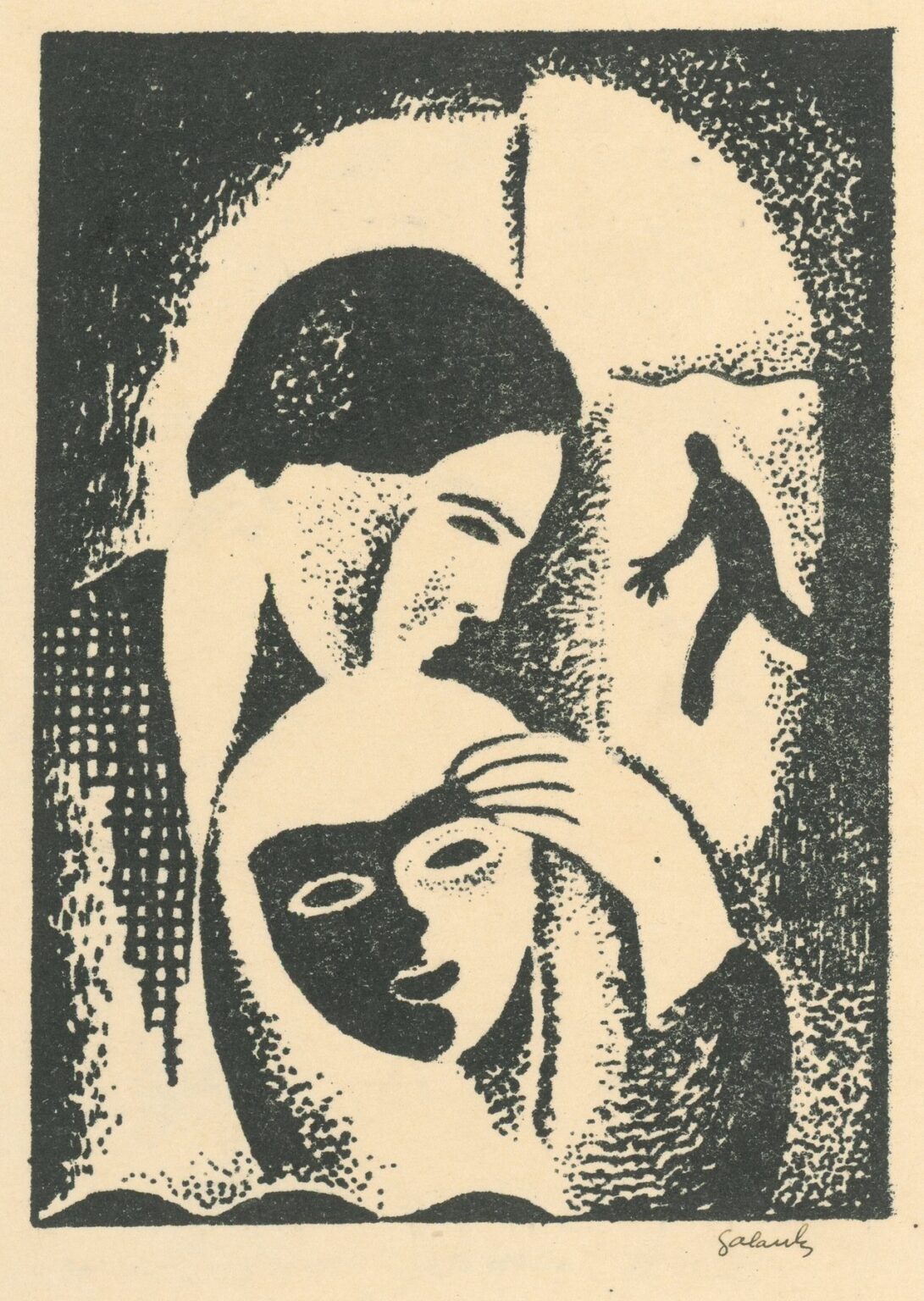

Mikuláš Galanda’s Lovers (1924) is a masterwork of early Slovak printmaking that captures the interplay of desire, identity, and concealment through a deceptively simple composition. Executed in black ink on paper, the image depicts two figures entwined in an intimate embrace, one tenderly lifting a veil or cloth to reveal the other’s face. Behind them, an indistinct silhouette moves toward or away from the scene, adding psychological depth and narrative ambiguity. Far from being a mere illustration of romantic affection, Lovers delves into themes of secrecy, self-revelation, and the transformative power of human connection. Through skilful use of positive and negative space, rhythmic stippling, and bold contours, Galanda invites viewers to consider not only what is revealed by the lovers’ gesture, but also what remains hidden in shadow.

Historical and Artistic Context

The year 1924 found Czechoslovakia in the throes of nation-building and cultural experimentation. Formed in 1918 from the ashes of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the young republic fostered an artistic environment that blended folk traditions with avant‑garde innovations from Paris, Vienna, and Berlin. Galanda, having studied in Budapest and Munich, brought to Bratislava a deep appreciation for graphic media—woodcut, lithography, and pen‑and‑ink—that he saw as essential for reaching a broad public. His involvement with the Život (Life) magazine and participation in exhibitions alongside dedicated printmakers positioned him at the forefront of Slovak modernism. In Lovers, created in 1924, Galanda synthesizes these influences, demonstrating how the medium of print could convey both decorative beauty and profound psychological nuance.

Galanda’s Evolution as a Printmaker

Mikuláš Galanda’s trajectory as a printmaker began in the early 1920s, when he turned away from purely academic painting to explore the expressive potential of black‑and‑white imagery. His initial woodcuts revealed a fascination with simplified forms and rhythmic patterns, but he soon introduced stippling and cross-hatching to achieve subtler tonal gradations. By 1924, he had mastered a hybrid approach—combining the stark contrasts of relief printing with the delicate textures associated with intaglio techniques. Lovers exemplifies this evolution: the tightly controlled areas of black ink are offset by fields of stippled tone, creating a visual tension between flat silhouette and volumetric suggestion.

Composition and Spatial Design

The composition of Lovers revolves around a vertical axis created by the two central figures. The primary figure—seen in profile—lays bare one side of a face beneath a draped cloth, its hand delicately poised at the top of the veil. The second figure, partially obscured, presses close from behind, their face veiled yet suggested through the curve of cheek and hairline. This interlocking arrangement forms an intimate, almost enclosed space that contrasts with the more open field around them. To the right, a small, distant silhouette strides toward the lovers or retreats into the shadows, its ambiguous posture adding narrative intrigue. Galanda balances these elements within a rectangular frame, employing negative space to emphasize the lovers’ centrality and the quiet drama of their gesture.

Line, Contour, and Stippling Technique

Galanda’s mastery of line work is immediately apparent in Lovers. Bold contour lines define the figures’ profiles, the drapery, and the edge of the masking cloth with assured precision. Within these outlines, Galanda introduces stippling—a meticulous pattern of dots—to model form and suggest atmospheric depth. The stippled areas vary in density, creating transitions from light to dark that lend the figures a sculptural presence despite the flatness of the black‑and‑white medium. Cross-hatched strokes accentuate shadows along the figures’ necks and shoulders, while small flecks of white paper ground peek through to suggest highlights on cheekbones and fabric folds. This combination of drawing and printing sensibility allows the image to breathe with subtle gradations, elevating it beyond mere silhouette.

Use of Positive and Negative Space

A defining characteristic of Lovers is Galanda’s use of positive and negative space to articulate emotional content. The lovers themselves are rendered in positive black ink, drawing the viewer’s eye to their interaction. In contrast, the background remains largely unprinted paper, save for the small silhouette that moves through it. This vast field of negative space acts as a visual and metaphorical void, isolating the lovers in their private world. The unprinted areas within the draped cloth—even on the figures’ bodies—create pockets of light that emphasize the reveal of the face and the tenderness of touch. In this way, the interplay of black and white becomes an integral part of the narrative: what is hidden in shadow and what is revealed by absence.

Symbolism of Veiling and Unveiling

The act of lifting a veil or cloth has deep symbolic resonance across cultures, often associated with revelation, transformation, or initiation. In Lovers, Galanda harnesses this motif to explore themes of intimacy and trust. The partially unveiled face suggests a transition from concealment to exposure—an emotional vulnerability that only a trusted partner can witness. At the same time, the act of unveiling implies power dynamics: the one who reveals holds agency, while the revealed surrenders control. Galanda’s choice to depict the veil as a simple white shape against the black ink heightens its symbolic weight, turning it into a radiant threshold between hidden and known, shadow and light.

The Silhouette: Observer or Participant?

The small, distant silhouette to the right of the lovers introduces a compelling ambiguity. Is this figure a third party approaching to interrupt or witness the lovers’ embrace? Or does it represent a memory, a fleeting thought, or an absent presence? Its anonymity—no discernible features, just a dark shape against the unprinted paper—allows multiple readings. In formal terms, the silhouette balances the composition, countering the mass of stippled tone on the left. Psychologically, it underscores the lovers’ isolation: they inhabit a space apart from the world, with the silhouette either reinforcing their solitude or hinting at external pressures that encroach upon their intimacy. Galanda’s inclusion of this motif enriches the work’s narrative complexity.

Emotional Atmosphere and Psychological Depth

Beyond the technical virtuosity, Lovers conveys an emotional atmosphere that resonates with universal themes of love and secrecy. The close cropping, the enveloping drapery, and the tender gesture combine to produce a sense of hushed devotion. The lovers’ faces—one fully revealed, the other lost in shadow—suggest layers of emotional experience: joy and ecstasy tempered by introspection and perhaps longing. The stippled textures evoke a sense of gentle murmur, as if the figures inhabit a private realm where sound is softened and time slows. In its psychological depth, Lovers aligns with Expressionist interests in inner life, yet Galanda’s restraint—eschewing overt distortion or dramatic line—marks a distinctive approach rooted in quiet intensity.

Relation to Slovak Folk Tradition

Although Lovers is deeply modernist in its formal language, echoes of Slovak folk tradition persist in its rhythmic patterns and decorative sensibility. The stippling recalls the dot motifs found in regional embroidery, while the flowing drapery shapes echo carved wooden altarpieces. Galanda earlier collaborated on folk-inspired graphic cycles, and in 1924 he remained committed to integrating local cultural forms with contemporary art. By abstracting folk motifs into his stippled textures—stripped of literal reference—he crafted an image that feels both familiar and refreshingly new. This fusion of modern technique and folk inheritances is central to Galanda’s vision of a Slovak modernism that honors roots while embracing innovation.

Technical Execution and Medium Mastery

Although Lovers reads like a woodcut or lithograph, it was executed with pen, ink, and stippling techniques directly on paper—an unconventional but effective approach. The crispness of the black ink lines suggests a relief print’s clarity, while the nuanced stippling evokes intaglio’s tonal richness. Achieving uniform stippling by hand requires exceptional patience and control; Galanda demonstrates an uncanny precision, distributing dots in measured patterns that modulate smoothly from dense shadow to luminous highlight. The unprinted paper ground functions as negative ink, demanding careful planning to preserve areas of intended light. Galanda’s daring synthesis of drawing and printmaking idioms highlights his technical mastery and willingness to push medium boundaries.

Comparative Analysis: European Context

In the broader context of 1920s European art, Lovers shares affinities with artists who explored intimacy and abstraction. German Expressionists such as Erich Heckel and the Die Brücke group used intense line and simplified forms to depict emotional states; however, their work often emphasized angular distortions and vivid color. Galanda’s approach remains more measured, privileging tonal subtleties over chromatic drama. In France, lithographers like Suzanne Valadon and Théophile Steinlen portrayed lovers with warmth and decorativeness, yet with less formal experimentation. Galanda occupies a unique niche: combining the graphic traditions of Central Europe with a modernist restraint that prefigures post‑war abstraction.

Reception and Legacy

When Lovers first appeared in exhibitions in Bratislava and Prague, it was lauded for its elegant synthesis of technique and emotion. Contemporary critics recognized Galanda’s innovative stippling method and his capacity to convey intimacy through print-like drawing. Over the ensuing decades, the work has been celebrated in retrospectives as a high point of interwar Slovak graphic art. Its influence can be traced in later Slovak printmakers and illustrators who adopted stippling and abstraction to explore personal themes. Lovers remains a teaching example in art academies, demonstrating how mastery of line and tone can yield profound narrative and psychological resonance.

Conservation and Presentation

As a fragile ink drawing on paper, Lovers requires careful conservation. It is typically framed behind UV-filter glass with acid‑free matting, ensuring that both the ink and the paper ground remain stable. Controlled humidity prevents buckling, while minimal light exposure preserves the crispness of the stippling against the ivory ground. When displayed, galleries often pair Lovers with other works from Galanda’s 1920s period to highlight its innovations, offering viewers insight into the evolution of Slovak printmaking.

Conclusion

Mikuláš Galanda’s Lovers (1924) transcends its medium to become a timeless meditation on intimacy, identity, and the interplay of concealment and revelation. Through expert stippling, bold contours, and judicious use of positive and negative space, Galanda crafts an image that pulsates with emotional depth. The partially unveiled face, the tender embrace, and the mysterious passing silhouette combine to create a narrative open to interpretation yet deeply felt. Situated at the crossroads of Slovak folk tradition and European avant‑garde, Lovers affirms Galanda’s pioneering role in modern printmaking and his enduring capacity to capture the universal wonders of human connection.