Image source: wikiart.org

A Portrait That Turns Pattern Into Presence

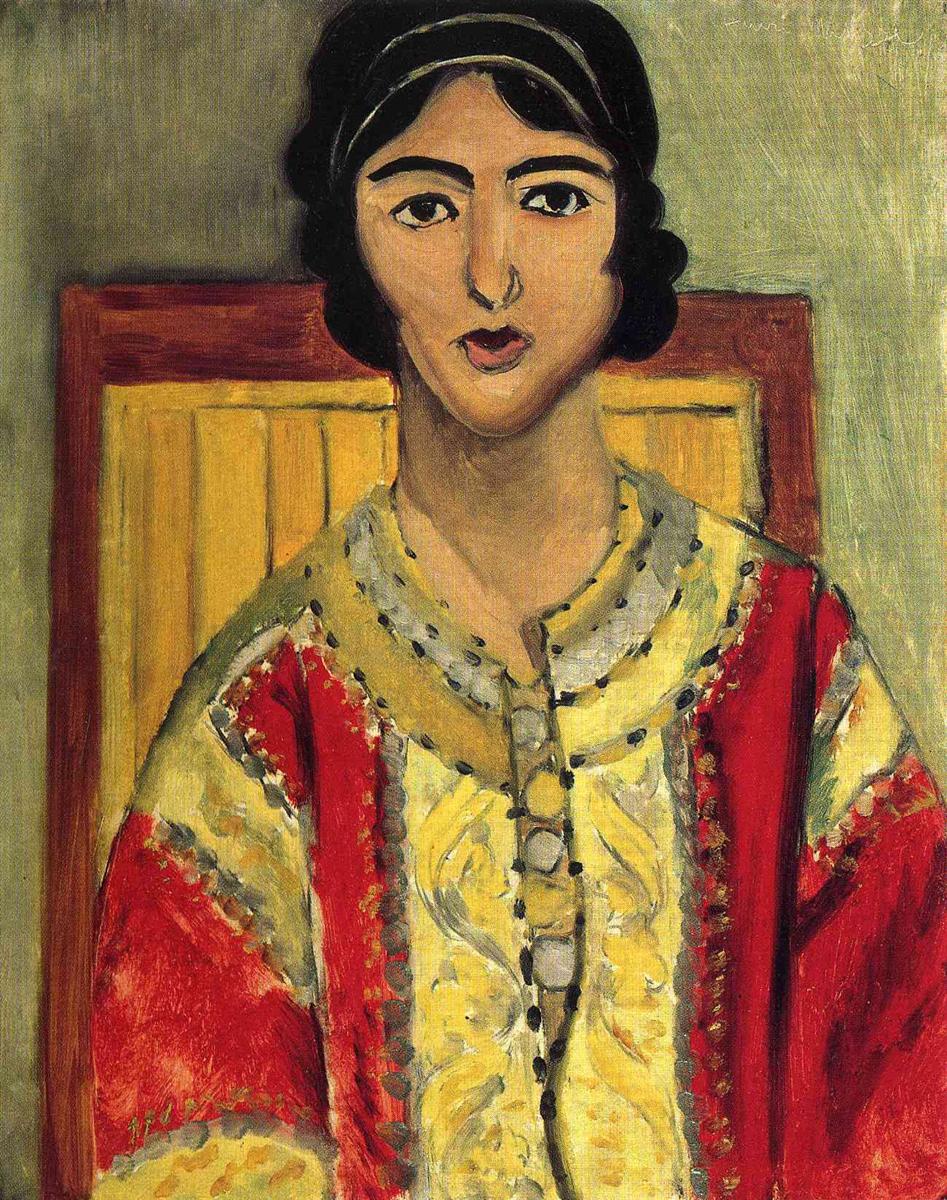

Henri Matisse’s “Lorette with a Red Dress” (1917) shows a seated young woman facing the viewer head-on, her shoulders squared and her gaze steady. The image is at once frontal and intimate. It is built from a few decisive planes—green wall, wooden chair back, and the flattened, richly colored garment—that frame the face like an icon. Rather than multiplying details, Matisse concentrates on relations: the dialogue between red and yellow in the dress, the measured geometry of the chair behind her, the calm green field enveloping everything, and the black contours that anchor each shape. The result is a portrait where costume becomes structure and color carries psychology.

The Composition’s Simple, Powerful Scaffold

The composition rests on a near-symmetry that Matisse subtly unsettles. The head occupies the vertical center; the shoulders expand left and right in a broad trapezoid; the chair back rises like a golden panel. Yet nothing is mechanical. The face tilts a breath to the sitter’s right; the neckline slants; the right sleeve bulges slightly more than the left. These small deviations keep the image alive. Cropping is tight—hair touches the top edge, sleeves meet the sides—so the sitter fills the visual field. The shallow depth compresses figure, chair, and wall into layered planes, giving the portrait the clarity of a sign without sacrificing warmth.

Frontal Portraiture and the Logic of the Icon

Matisse borrows from the icon’s frontal grammar—central head, upright torso, luminous panel behind—then translates it into modern color. The chair behaves like a gold ground: a rhythmic array of vertical slats held in a reddish frame. It confers calm solemnity on the sitter, while the green wall acts as a cool halo around the entire figure. Instead of heavenly symbolism, Matisse offers pictorial order. Frontality is not stiffness here; it is a device that focuses all variation—the tilt of the head, the play of the garment, the flicker at the mouth—where they matter most.

The Red Dress as Engine of the Picture

The garment does more than identify; it builds the composition. The sleeves and outer panels carry a saturated, slightly textured red that reads as weight and warmth. Down the center runs a broad yellow field—embroidered or brocaded—edged with dotted black and gray scallops. The yellow panel is not pure; it drifts between pale gold and straw, catching light like a low-burning flame. That panel functions as a vertical path through the painting, guiding the eye from collar to hem and doubling the chair’s vertical slats behind it. Pattern becomes structure: the dots and scallops slow the eye, allowing the plain fields of red to resonate. By limiting ornament to a few repeated motifs, Matisse lets the dress act as architecture rather than decoration.

A Restricted Palette That Feels Abundant

Although the painting contains only a handful of hues—green, red, yellow, black, a few wood browns—the relationships are so carefully tuned that the palette feels ample. The red is warm and luxurious, but it is moderated by cool neighbors: the green wall and the gray-silver notes in the trim. The yellow brightens the center without glaring thanks to its earthy undertone, which echoes the wooden chair. Black does triple duty: it outlines features, stitches the garment’s edging, and anchors the hair. By withholding high chroma in the background and chair, Matisse ensures the garment and face glow without shouting.

The Face as a Field of Decisions

Matisse constructs the face with a few large planes and a set of resolute contours. The eyebrows are dark, wide arches that establish the gaze before the eyes themselves are fully read; the eyelids are definite sweeps of black; the nose is a firm column modeled with minimal value shifts; the mouth is a small, slightly open shape that gives the expression its alert, speech-ready quality. The skin is a warm ocher-rose, brushed in broad strokes that leave the surface breathing. There is no atmospheric modeling around the features; instead, edges do the work. The result is likeness by structure, not by micro-detail—a face that remains legible from across a room and nuanced up close.

The Role of the Chair Back

The chair back is crucial to the portrait’s equilibrium. Its vertical slats rhyme with the vertical panel of the dress and with the figure’s upright bearing. Its ocher-gold color acts as a mediating middle between the cool green wall and the warm red garment, knitting the palette together. The reddish frame of the chair repeats the dress’s outer color without competing for attention. In compositional terms, the chair is a stabilizer; in psychological terms, it suggests a seated steadiness, a composed readiness that matches the sitter’s gaze.

Black Contour as Structure and Ornament

Matisse’s black is never a mere outline; it is a constructive element. Around hair, eyelids, nostrils, and lips it defines essential transitions, sharpens the design, and gives the face its authority. In the garment, dotted black stitches punctuate the yellow field, converting the central panel into a rhythmic band. At the collar, bolder curves of black and gray articulate the neckline, underscoring the rise of the neck and the tilt of the head. Because these darks are applied with a loaded brush that thickens and thins, their calligraphy carries the painter’s hand—supple, decisive, and varied.

Brushwork, Texture, and the Truth of the Surface

The portrait declares its materiality. In the wall, strokes run horizontally and diagonally, leaving a soft, chalky texture that keeps the background alive while remaining recessive. In the dress, paint sits thicker, especially along seams and edges where impasto catches real light; this makes the garment feel tactile without illustrative detail. The yellow center shows broken strokes that mimic the play of embroidery, while the red sleeves carry broader sweeps that read as cloth under weight. On the face, the brushwork is quieter but remains visible; slight variations in pressure shape cheek and chin. Everywhere, the surface tells us how the image was made—no polish, no glaze of concealment—so that looking becomes a record of decisions rather than a search for hidden technique.

Space as Shallow Stage

Depth is minimal and deliberate. The sitter is pressed close to the picture plane; chair and wall nest just behind. Overlap and scale deliver all the depth needed: head in front of chair, chair in front of wall. This shallow stage gives pattern the authority it needs to function structurally. It also keeps the viewer in direct relation to the sitter, as if seated across from her. The portrait does not invite us to wander in; it invites us to attend.

Lorette as a Constant and a Variable

Lorette, a favored model in 1916–1917, appears across a series of paintings in which Matisse tests poses, lighting, and costume. In this version, her identity and the red dress’s identity are inseparable: the garment is not a prop but a collaborator, a way for the artist to explore how color and pattern can shoulder the expressive work often assigned to facial expression alone. The sitter’s direct gaze and slightly parted lips deliver personality, but the largest part of her presence arrives through the order she inhabits—the verticals, the rhythm of trim, the balance of cool and warm. In this sense the portrait is a joint portrait of Lorette and of painting itself.

Ornament and Order in Productive Tension

Matisse admired ornament—Islamic tile, textiles, embroidery—but always submitted it to order. The dotted edging, scalloped seams, and brocade-like central field provide richness; the vertical chair slats and the garment’s axial panel restrain and guide that richness. Because ornament is located at borders and along the central spine, it reinforces shape instead of dissolving it. You feel pleasure and discipline at once, an equilibrium that would become a hallmark of his later interiors in Nice.

Light as Unifying Envelope

The light is broad and even; it kisses the sitter and dress without carving deep shadow. Highlights on the yellow panel are simply paler yellows; on the face they are lifted flesh tones; on the chair they are small licks of creamy ocher catching the slat ridges. By avoiding theatrical illumination, Matisse grants the portrait a calm timelessness. This envelope of light allows color to be the principal narrator of mood and prevents descriptive modeling from competing with design.

The Psychology of Stillness

Portrait psychology here arises from posture and relation, not from melodramatic gesture. Lorette’s shoulders are level; head poised; gaze attentive. The mouth, just open, suggests breath and thought rather than talk. The dress, heavy with color yet contained by pattern, mirrors this inward steadiness. Even the green wall participates: its coolness keeps heat in check, like a fresh room on a summer day. The overall feeling is composed readiness—someone who is present, alert, and comfortable in the attention the painting gives and asks.

A 1917 Temperament

The date matters. In 1917, the flamboyance of Fauvism has been tempered into a reflective clarity. Black regains an organizing role; color remains intense but is harnessed to structure. The portrait belongs to that moment: it is bold without aggression, concentrated without austerity. The palette is modern but classical in its discipline; the frontality nods to older portrait conventions while asserting its own contemporary syntax.

Dialogues With Tradition and the Avant-Garde

Matisse converses with several traditions at once. The icon’s frontal dignity, the Renaissance portrait’s respect for the sitter’s head-and-shoulders presence, and the modernist flattening of space all meet here. Unlike Cubism’s fractured planes or Expressionism’s theatrics, Matisse’s modernity is constructive: simplifying forms until they cooperate in a stable design, then letting color carry emotion. The viewer experiences innovation as lucidity, not shock.

How the Eye Travels

The painting proposes a satisfying route. Many viewers start at the face—eyes and mouth held by dark contours—then slip down the neckline into the dark-dotted braid of the yellow panel. From there the gaze expands across the red sleeves and returns along the scalloped trim to the collar. The chair’s verticals lift the eye back to the face, and the cool green wall gives a final restful pause. This loop is anchored by alternating contrasts: dark against light at the features, warm against cool at the edges, saturated against muted across the garment and chair. The circuitry makes the portrait inexhaustible; each pass reveals a new seam, a brush ridge, a small correction at an edge.

Material Facts That Reward Close Looking

Look closely and the surface offers tangible pleasures. A thinned underpaint peeks through the green at the upper right, softening the wall. The black at the hairline frays into the background, letting air seep between head and wall. Along the collar, gray strokes sit on top of yellow, shifting temperature and implying the cool sheen of thread. On the red sleeve, a vertical pass of the brush leaves a slight ridge that catches real light, making the fabric seem to glow from within. These material facts ground the portrait in the here-and-now of painting.

Why This Portrait Endures

“Lorette with a Red Dress” endures because it solves a demanding problem with clarity: how to give a person weight and presence using a language committed to flatness, pattern, and simplified form. Matisse’s answer is to make every component—the chair’s geometry, the garment’s rhythm, the contours of the face—serve both likeness and design. Nothing is extraneous; everything contributes. The painting reads instantly and grows slowly, accommodating both a quick glance and prolonged attention. It shows how color can be thinking, not just feeling; how ornament can be structure; how a modern portrait can be frank about its surface and still deliver depth of presence.

A Closing Reflection

To sit with this portrait is to experience composure. The picture offers a calm order—verticals, measured accents, generous fields of color—in which a human being can appear without being overexplained. Lorette’s poised gaze meets ours across a garment that is at once sumptuous and disciplined, across a chair that turns into a golden panel, across a cool wall that holds the heat of red and yellow in balance. The painting teaches how attention itself can be an art: select what is necessary, set relations clearly, and allow color and contour to speak. That lesson remains fresh each time the viewer returns.