Image source: wikiart.org

A Turban, a Garden, and the Architecture of Color

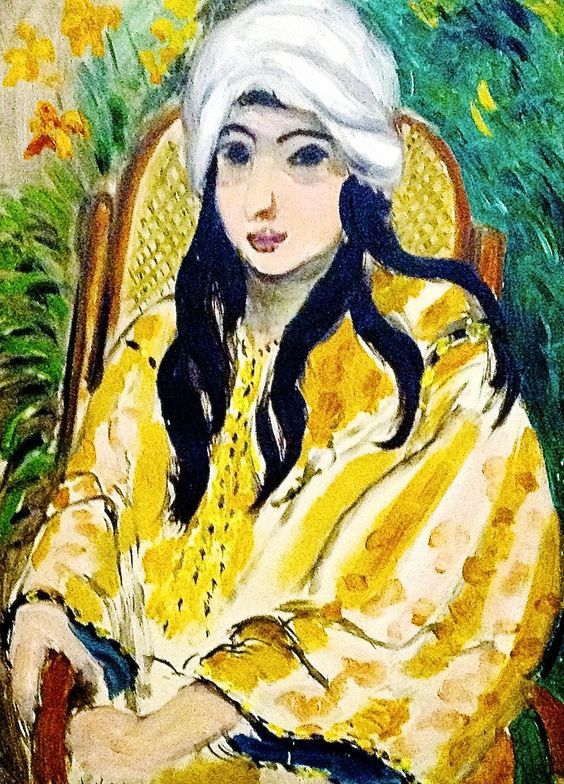

Henri Matisse’s “Lorette in a Turban” (1917) compresses the sensation of an encounter into a few fully charged elements: a young woman seated in a wicker-backed chair, a luminous white turban that crowns her head, cascades of black hair that frame and divide the yellow of her robe, and a vibrating ground of garden greens. The picture arrives with a single, memorable clarity at a distance, then, on approach, reveals a poetics of edges, temperatures, and intervals that make the image feel fresh each time the eye returns. It belongs to the cluster of works Matisse produced in 1916–1917 with his model known as Lorette, a series in which he tested how much presence could be delivered by the fewest possible pictorial decisions. Here the experiment is both intimate and theatrical: a domestic chair becomes a throne, a turban a halo, a robe a field of weather.

A Composition Built to Seat Presence

Matisse brings Lorette close to the picture plane so that she occupies the canvas like a new piece of furniture in the room. The chair’s oval back forms a warm, honey-colored frame around the head and shoulders, while its vertical stiles repeat the figure’s own geometry. The sitter’s posture is slightly forward, one hand perched on the armrest, the other near the lap, which sets a subtle diagonal that animates the otherwise frontal pose. The composition’s architecture is deceptively simple: the head is the apex of a shallow pyramid whose base is the sweep of the yellow robe. The triangular order stabilizes the composition even as the flowing hair and fabric keep it from stiffening. The result is a picture that wears its order lightly; you feel it rather than see it diagrammed.

The Turban as Crown and Light Source

The white turban is the painting’s brightest note and its conceptual center. It catches and reflects the most light, establishing the high key that allows all other colors to relax into place. Matisse builds it with thick, opaque passes that curl like soft stone, and the ridges of paint physically catch the ambient light, making the object radiate even in reproduction. Beyond its optical function, the turban is an iconographic device: it crowns Lorette without exoticizing her into a costume mannequin. It echoes the picture’s larger project of dignifying the everyday through the sovereignty of color and line. Against the surrounding greens and the robe’s yellows, the turban becomes both a cool flare and a compositional stop that keeps the eye from drifting upward out of the frame.

Black Hair as the Picture’s Calligraphy

If the turban supplies brilliance, the hair supplies structure. Matisse draws the hair as continuous S-curves of glossy black that fall over the robe in thick, legible ribbons. These curves do several kinds of work at once. They carve the yellow field into coherent shapes, preventing the garment from reading as one undifferentiated mass. They stage a rhythm across the figure that the eye can follow without fatigue. And they reaffirm Matisse’s conviction that a painted line, if placed with conviction, can carry as much psychological and structural information as any amount of modeling. The hair is calligraphy in the strict sense: a writing performed with the brush, recording pressure, speed, and intention.

Color as Climate and Character

The palette is deliberately restrained: greens in multiple temperatures for the garden ground, golden ochres and lemony yellows for the robe, a honey-brown for the chair, dense black for hair and contour, soft flesh tones modulated with peach and gray, and the white of the turban. Because the scale is so focused, the relationships are easy to read and emotionally exact. Yellow becomes warmth, hospitality, the field of personality; green becomes the enveloping environment, a cooling force that keeps the yellow honest; black frames and concentrates; white releases a breath of air into the upper register. Matisse places small, strategic accents—a flick of coral at the lips, deeper rose in the cheeks, a cool shadow along the jaw—to keep the face alive without breaking the general harmony.

The Garden Without Viewpoints

The background is not a window onto a receding space but a pressed field of vegetation. Fern-like fronds and flower bursts are laid in with brisk, angled strokes, creating a lively but shallow zone that behaves like a textile. The foliage’s directionality appears to radiate from behind the sitter, as if nature itself arranged a nimbus around her. This is not illusionism; it is an agreement between figure and ground that grants the portrait breadth without surrendering the canvas to depth. In the absence of perspectival corridors, color carries the sense of air. Greens cool toward turquoise where they meet the turban and warm toward sap where they approach the chair, suggesting atmosphere with the simplest of means.

Drawing with the Brush: Black as Architecture

Matisse’s black is neither outline nor afterthought; it is a structural color. He delineates eyebrows, eyelids, nostrils, and lip edges with sculptural certainty, and he declares the seam of the robe and the chair’s profile with strokes that thicken and thin according to need. Because black sits on top of neighboring colors without blending, it reads like ironwork—supporting spans and hinges—rather than like an encircling fence. This is a crucial part of Matisse’s modernism in 1917: drawing and color are not separate tasks but simultaneous acts. The contour is not a skeleton waiting for flesh; it is the painting’s bone and muscle all at once.

The Face as Planes and Temperament

Up close, the face resolves into a set of tempered planes. The forehead is a warm, even table of light; the eye sockets are gently cooled to hold the pupils; the nose is a narrow, bright ridge that turns into a triangle of shadow; the lips are compact and considerate, with color deepest at the center and cooler at the corners. Matisse refuses descriptive fuss—no eyelashes counted, no pores cataloged—and instead trusts relationships between these planes to carry likeness and temperament. Lorette’s gaze is direct yet unaggressive, steady without stiffness. The portrait converts psychology into design and then back into psychology, a loop that explains its abiding freshness.

Fabric Turned Into Landscape

The yellow robe sprawls like a small landscape across the lower two-thirds of the canvas. Matisse makes it a terrain of warm lights and cooler pockets, modulated with quick strokes that record the garment’s weight without pinning it down. Pattern appears as dashes and small ovals that drift around seams and ruffles, never so regular as to read as printed textile but sufficient to quicken the surface. In several places the robe’s yellow falls into cream where light gathers, creating a satisfying counterpoint with the white turban. The garment is not ornament laid on top of the figure; it is the field in which the portrait’s big color chord is struck.

Chair as Human Measure

The cane-backed chair does not compete for attention, but it is indispensable. Its warm honey color mediates between the robe’s yellows and the greens behind; its curve around the sitter’s shoulders clarifies posture; its woven pattern is stated with a few pale dabs that admit air without chattering. The chair is the painting’s human scale. By recognizing it, we feel how near we are to Lorette, how domestic the scene is despite its aura, and how Matisse anchors even his most decorative portraits in the facts of sitting and seeing.

Light as an Even Envelope

The light across the picture is calm and broadly distributed. There is no spotlight punching holes in the composition, no hard-edged cast shadows to dramatize depth. Instead, illumination acts like a general climate that reveals volume gently and keeps the palette coherent. Highlights bloom on the turban, on the ridge of the nose, and along the robe’s folds, but none of them break the picture’s overall serenity. This kind of light corresponds to Matisse’s stated aim for an art of balance and repose. It gives the viewer a place to rest without dulling the senses.

1917: A Year of Discipline and Transition

Historically, “Lorette in a Turban” stands at a hinge. The Fauvist blaze of the previous decade had been tempered into a palette where black returned as a structural tone and large color fields did the emotional work. Within a few years Matisse would begin the Nice period, with its odalisques, patterned screens, and Mediterranean luminance. This portrait anticipates that shift: the turban, the robe’s ornamental logic, and the garden-as-textile all foreshadow the decorative splendor to come. Yet the painting also retains wartime discipline: reduced chroma compared to Fauvism, an insistence on contour’s authority, and an economy of elements that keeps the image lucid.

Orientalism Recast as Studio Poetics

A white turban and a richly colored robe inevitably borrow from Orientalist repertories that fascinated Western painters. Matisse knew those visual vocabularies well; he transformed them. Rather than staging an exotic theater, he distilled a few signs—a headwrap, a golden garment, a garden atmosphere—and reorganized them into a studio language about light, color, and rest. Lorette is not a fantasy type; she is a known collaborator whose intelligence looks out from the picture. The painting thus sidesteps the cliché of costume and turns toward a modern poetics: familiar objects reformatted into clear relations.

The Eye’s Itinerary and the Rhythm of Looking

Matisse choreographs a graceful route for the viewer. Most eyes enter at the white turban, drop to the dark iris of the right eye, cross the bridge of the nose to the mouth’s small coral flare, and then trace the black hair as it slides over the robe. From there the gaze travels across the garment’s yellow sea to the hand at the chair arm, back up the chair’s curve, and into the garden greens that gently push it upward toward the turban again. This loop is stable because each turn is punctuated by a clean value contrast: white against green, black against yellow, warm skin against cool background. The portrait holds attention not by cataloging details but by establishing a rhythm that the eye enjoys repeating.

Material Facts That Reward Close Viewing

Stand close and the surface tells its own story. The turban’s whites vary from thick impasto to thin, chalky scumbles; the garden greens include quick, almost dry passes that leave the weave of the canvas visible; the robe’s yellows are interleaved with umbers and creams that record the brush’s physical path. There are modest pentimenti where a contour was adjusted at a sleeve or the jaw, evidence of looking revised in real time. These facts matter because they keep the image rooted in the world of making. Presence here is not merely depicted; it is built in layers of touch.

Why This Portrait Endures

“Lorette in a Turban” endures because it offers a clear and generous answer to a hard question: how little is necessary to conjure a living person? Matisse chooses a handful of essentials—white turban, black hair, yellow robe, green garden, warm face—and binds them with authoritative drawing so that the portrait reads at once and rewards without exhaustion. It makes no claim to psychological drama, yet it feels deeply human. It stages no theatrical depth, yet it breathes. It flirts with decorative richness, yet it never abandons structural clarity. In short, it accomplishes the equilibrium Matisse prized: an image in which the viewer can rest and from which the viewer can learn how to see.

A Closing Reflection on Balance, Dignity, and Ease

Look again at the small thing the painting does: it lets a white shape sit on a field of green without glare; it lets black lines soften into hair while remaining lines; it lets a yellow garment be sumptuous without becoming noisy. These are not trivial achievements. They are the fruit of discipline and affection, of a painter who believed that the world could be organized into a few truthful relations and that doing so would increase, not diminish, its beauty. Lorette sits before us with a calm that is not empty but concentrated, the calm of a portrait that knows how it was made and why.