Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

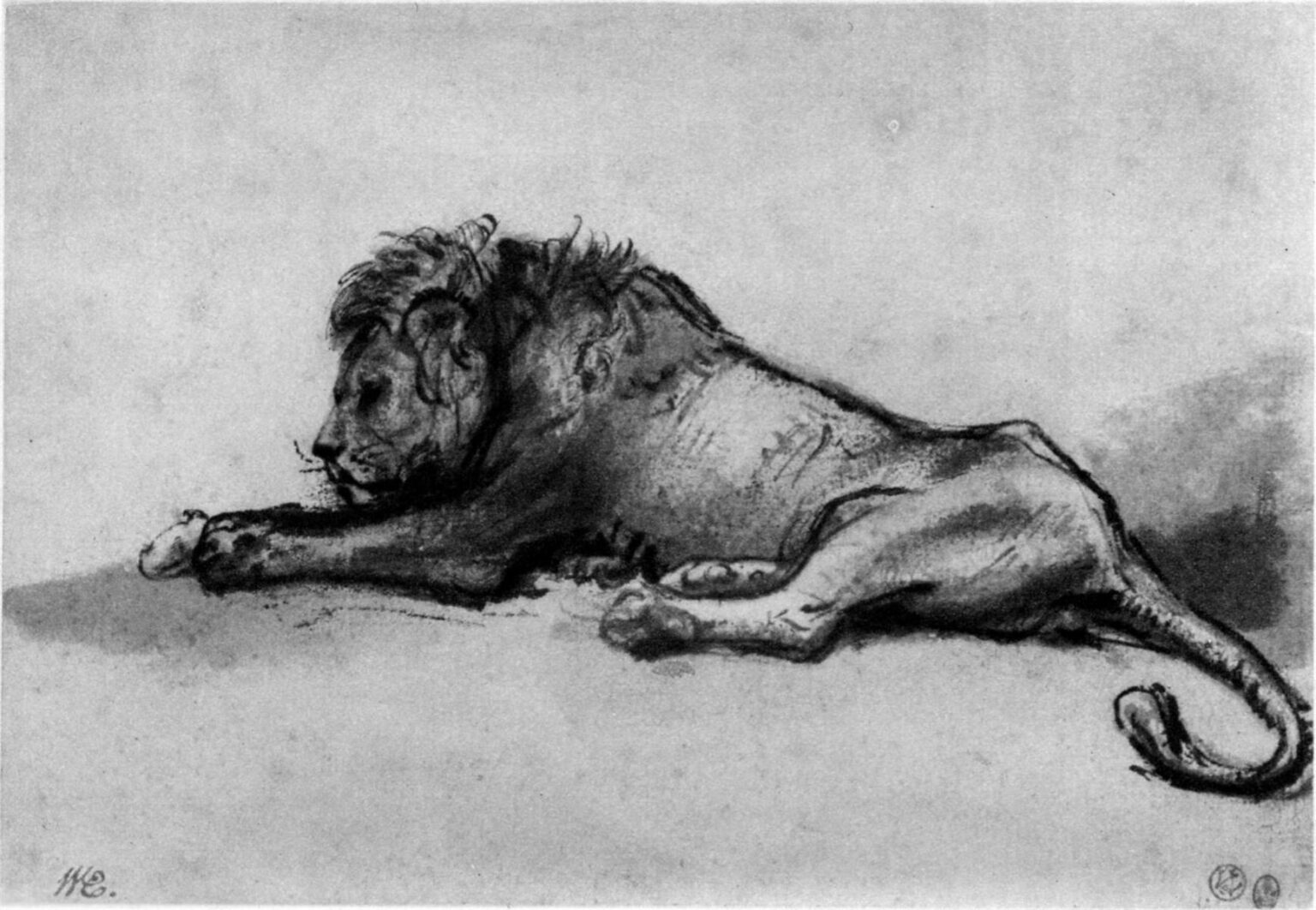

Rembrandt’s “Lion Resting” from 1652 is an unassuming sheet that roars softly. Drawn in chalk and ink with quick, confident touches, it presents a male lion stretched full-length across the page, head lowered toward his outstretched forepaw, body tapering to a skinny, whip-like tail. There is no scenery, no cage, no theatrical rock to perch on—only the animal’s weight, breath, and the subtle vibration of watchfulness that lingers even in repose. The drawing belongs to a small cluster of Rembrandt’s animal studies from the early 1650s, likely made after close observation of creatures in traveling menageries or local collections. What makes this sheet singular is the artist’s ability to say “lion” with the fewest possible marks, while giving the viewer an experience of living presence rather than zoological description. The result is a portrait of power at rest, as direct and intimate as a face seen across a quiet room.

The First Impression And The Arc Of The Body

The composition seizes you with a line: from the thick mane at left to the knot of the tail at right, the lion’s body curves like a bow lying on the ground. This long, low arc is not just outline but energy. It organizes the sheet’s empty field and turns stillness into suspended motion, as if the animal could, with a single flex, spring upright. Rembrandt positions the head slightly higher than the spine, directing attention to the muzzle and eyes without upsetting the languid profile. The paw in front, a pale oval capped with dark claws, punctuates the left edge like a quiet period at the end of a sentence. The rear legs are tucked, their joints knuckling the paper with a few decisive strokes. Everything is economical, but nothing is generic: the curve of the stomach, the bulge of the rib cage, and the shallow depression along the flank read as a specific body settled into a specific pose.

Head, Mane, And The Psychology Of Watchfulness

Although the lion is resting, his head preserves a sovereign alertness. Rembrandt lowers the chin toward the paw and shades the socket to deepen the eye, yet a few sparks of white along whisker and cheek lift the face out of sleep into something like concentration. The mane is handled differently from the body; it is not smoothed by wash but agitated by short, scratchy strokes that make the fur feel thick, heat-keeping, and slightly tangled. This difference in textures moves the viewer’s attention to the head as the seat of character. The lion’s mouth is closed, but there is weight behind the lips, a sense of strength merely idling. The head’s angle—neither frontally confrontational nor in total profile—lets us feel the intelligence that governs the body without turning the animal into a human caricature. It is not anthropomorphism to say the lion seems to be thinking; it is fidelity to the way animals attend to the world when they are still.

Hands, Feet, And The Grammar Of Weight

Rembrandt’s lions are convincing because their feet are convincing. The forepaw in this sheet is a masterpiece of shorthand: a rounded plane for the pad, two notches for the toes, a stripe of shadow where claws sheath, and a few abraded dots suggesting old calluses. The paw makes contact with the ground; you can almost feel the grit. The rear foot, tucked under the bulk of the body, is drawn with even greater economy—only the bony knuckle and the blunt oval of the pad break the smoothness of the flank—but the posture registers as absolutely right. His grammar of weight is exact: mass sinks where it should, relaxes where it can, and lifts where bone props it. That accuracy allows Rembrandt to leave so much space empty without compromising the animal’s reality; our minds fill the ground because our bodies recognize how weight distributes itself.

Line, Wash, And The Two Intelligences Of Drawing

The sheet unfolds as a duet between descriptive line and atmospheric wash. Rembrandt’s line is assertive and selective. It locks down the silhouette, demarcates joints, and flicks detail where needed: a notch inside the ear, a bundle of short strokes at the shoulder, a tight twist for the tail’s tip. The wash brings temperature and topography. It cools the shadowed belly, warms the flank, paragraphs the rib cage into soft planes, and anchors the body to the page with a dark, breath-like shadow beneath. Where the wash thins to nothing, the paper’s natural tonality becomes sunlight. Together, the two techniques create an animal you can almost touch: coarse mane, sleek hide, damp nose, dusty paw.

Negative Space And The Luxury Of Air

Half the beauty of “Lion Resting” comes from what Rembrandt refuses to draw. The upper two-thirds of the sheet is nearly empty, a calm field of pale tone. This negative space is not dead air; it is habitat made from light. It allows the animal’s low, heavy body to breathe. The emptiness also dignifies the lion. Without a constructed environment—no columns, no caves, no classicized savannah—the creature exists as a sovereign presence rather than as an actor in a narrative. The viewer is given the luxury of air and asked to supply nothing but attention.

Anatomy Seen, Understood, And Simplified

One senses the artist’s long acquaintance with anatomy beneath the drawing’s simplicity. He understands where the scapula rides under fur as the foreleg extends, how the rib cage flattens toward the abdomen, and how the pelvis knots the hindquarters. Yet he never diagrams. Instead, he reduces each anatomical fact to a gesture: a swelling wash, a knocked-back highlight, a broken contour. The result is clarity without pedantry. You read the lion’s structure as you would read the fall of a coat on a human figure—through the truth of surfaces, not the display of internals. This discipline of reduction is part of Rembrandt’s late style more generally: fewer marks, more meaning.

The Mood Of The Sheet: Power At Idle

What emotion does the drawing carry? Not drama, not sentimentality, but a kind of sovereign calm. The lion is neither threatened nor threatening. His tail curls in a loose question mark; his ear tilts but does not prick; his muzzle rests without slackness. It is the mood of an engine idling—power conserved, immediately available. That mood comes in part from the profile pose, which keeps the mouth and eyes in a single plane, and in part from the horizontal stretch, which quiets the posture even as it implies readiness. This mixture of ease and possibility is why the drawing feels alive hour after hour of looking; your eye senses that the scene could change in an instant.

A Lion In Seventeenth-Century Amsterdam

The Dutch Golden Age was saturated with images of the lion as emblem—on coins, maps, and civic coats of arms. Rembrandt knew this heraldic lion well, but he makes a different argument here. This is not the “Leo Belgicus,” the national symbol, nor the lion of Daniel’s den roaring under divine control. It is a living animal observed with respect. That shift from emblem to creature marks a humanistic turn in Rembrandt’s art of the 1650s: historical specificity and bodily presence replace allegorical stiffness. The choice to draw from life—very likely at a menagerie or collector’s yard—signals an ethic of truthfulness that runs through his landscapes, portraits, and still lifes from the same years.

Close Looking At Key Passages

A few passages model the drawing’s quiet brilliance. The neck ridge is nothing but two parallel scratches of dark, yet the viewer reads thick skin rolling over muscle. The mane’s leading edge dissolves into the cheek with three diagonal strokes and a smudge—enough to convert chaos of hair into the logic of growth. The hind leg’s contour is actually a series of segments that Rembrandt allows to breathe apart; the mind bridges them as skin stretched over bone. Beneath the body, a single sweated swipe of wash becomes ground, shadow, and a hint of dust disturbed by settling weight. At the tail, a knife-edged dark line ends in a small tuft of strokes, a witty reiteration of the entire sheet’s style: decisive followed by suggestive.

How The Drawing Teaches Us To Look

“Lion Resting” disciplines the viewer. At first you see the whole, then your attention breaks into reconnaissance of marks, then it recomposes into presence. You discover how few decisions are needed to convince you—how a paw requires only an oval and a notch, how an ear can be a triangle with a single bite taken out. The sheet trains the eye to find life in abbreviation, to accept the sufficiency of good choices, and to resist the modern craving for photographic detail. It is an apprenticeship in humility for audiences who are often impatient with suggestion.

Kinship With Other Animal Studies

Rembrandt’s other lions—reclining, yawning, turning—share this sheet’s mixture of observation and economy, but this version is especially poised between drawing and painting. It has more tonal modeling than his lightest pen studies and far less finish than the occasional presentation drawing. That middle register is where his most moving work often lives: enough specificity to convince, enough openness to breathe. The sheet converses beautifully with his studies of an elephant and with the quick sketches of dogs and oxen; in each case the artist refuses exoticizing theatrics and seeks instead the animal’s weight, posture, and gaze.

Technique, Paper, And The Evidence Of Time

The surface itself tells a story. The chalk’s dry grain skims the tooth of the paper; the wash sinks more deeply, pooling where the brush slowed and thinning where it sped. Occasional faint abrasions—erasures or lifted strokes—speak of revision. Rather than hiding such evidence, Rembrandt keeps it visible. Time becomes part of the drawing’s aura: time of watching the animal, time of deciding a stroke, time in the studio when the sheet was picked up again to reinforce a contour or deepen a shadow. The work wears its making like a patina, and that honesty binds viewer to maker.

The Viewer’s Vantage And The Ethics Of Proximity

Where are we standing? Not above the lion like a zoo visitor, not at the animal’s eye level like a rival, but a step back and slightly higher, a respectful human distance. The vantage acknowledges both curiosity and caution. It keeps the lion’s sovereignty intact; we observe without imposing ourselves. That ethical stance matters. In an era when wildness is often seen at screens’ remove, this drawing models nearness without domination—an encounter based on looking well rather than possessing.

Sound, Smell, And The Sensory Imagination

A strong drawing engages senses beyond sight. The scuffed wash under the body evokes the soft thud of a heavy animal settling. The darkening around the muzzle conjures a damp, warm smell. The mane’s scratchy texture suggests the rasp of rough hair under a hand. None of this is drawn explicitly, yet the credibility of forms allows the mind to build a sensory world. The more you attend, the richer it becomes: a flea flicked away by a twitch, a slow exhale, the faintest creak of a chain or rail somewhere off-page if the lion has been confined. Such details make the sheet less an image than a place.

Why The Image Still Feels Contemporary

Minimal means, maximal presence—that formula resonates with contemporary taste. Designers, photographers, and animal lovers recognize the power of leaving space around a subject, of trusting a few lines to carry a complex reality. The drawing also speaks to modern anxieties about power. This lion’s power is neither violent nor sentimental; it is grounded, controlled, ready. In a culture that often confuses loudness with strength, the sheet proposes a counter-image: authority as calm availability.

The Afterlife Of A Simple Pose

Many images are seen once; this one lingers. Part of its endurance lies in the pose’s rightness. Anyone who has watched a cat knows this exact extension of the forelegs, this way the spine lengthens into a line of rest, this curl of tail that keeps the animal’s geometry closed. The drawing wedges itself into memory because it answers, with accuracy and empathy, a familiar pattern of life. The lion here becomes archetypal without ceasing to be a particular creature.

Conclusion

“Lion Resting” is a small demonstration of large powers. With a handful of marks, Rembrandt composes weight, breath, and character. The long bow of the body, the thick mane’s agitation, the satisfying grammar of paws and joints, the duet of line and wash, the amplitude of negative space—together they turn a blank sheet into a place where power sleeps with one eye open. The drawing is not a trophy but a conversation; it trusts the viewer to meet abbreviation with attention and to find, in the quietest of images, the richest of presences. In an oeuvre crowded with kings, apostles, city views, and biblical dramas, this simple lion claims a royal place: a sovereign creature, fully itself, inhabiting a page with dignity and calm.