Image source: wikiart.org

Historical Context And Why This Village View Matters

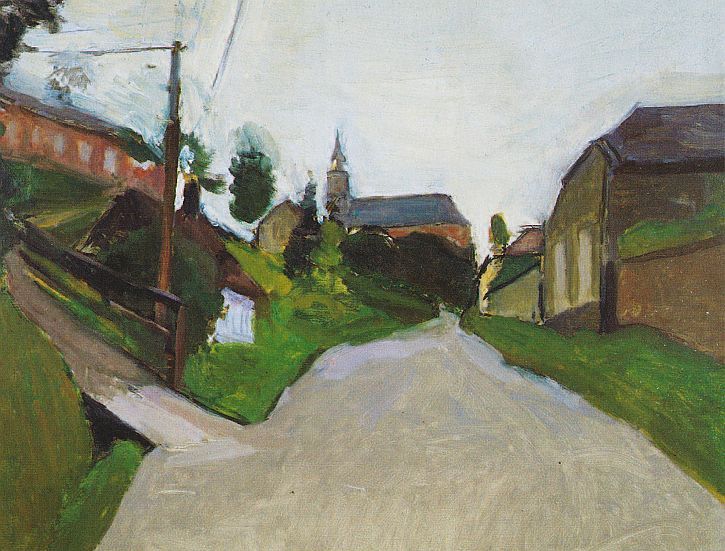

Henri Matisse painted “Lesquielles St Germain” in 1903, at a threshold moment when his art was shifting from academic finish to the structural clarity that would soon underpin Fauvism. Rather than chase grand Parisian motifs, he returned to northern France—Picardy—where a plain road, a sloping green and a church spire could become a laboratory for relations of plane, tone and color. The picture records a small hill town approached along a pale, ascending roadway. It looks modest, but it contains many of the ideas that would power Matisse’s later breakthroughs: a composition organized by a few large shapes, light treated as climate rather than spotlight, drawing achieved by adjacency of colors, and a surface that remains a designed field even while it hosts believable space. The modern detail of a telegraph pole and wire announces new rhythms entering rural life, just as Matisse’s new painting rhythms were entering modern art.

First Impressions: A Road That Pulls You In

The first sensation is of being drawn forward. A wide, light road rises from the lower edge and narrows as it climbs toward a nucleus of buildings crowned by a church steeple. The sky is a high, near-white field, clean and expansive. On either side, green banks and house façades lean inward, creating a funnel that invites entry. Nothing is fussy. The buildings are reduced to planes; the trees to soft crowns of tone; the sky to a scumbled, breathing field. It is a landscape you recognize at once: a village seen from the approach, the steeple the aim point for foot and eye.

Composition As A Funnel Of Planes

Matisse builds the rectangle from a few decisive elements. The road is an isosceles wedge that commands the foreground and bisects the picture, its edges drawing straight to the steeple. Two flanking masses—the right-hand house wall and the left-hand green slope with rail and pole—tilt inward, pinching space toward the distance. The horizon sits high, so most of the canvas is given to approach and sky rather than to the distant cluster itself. The telegraph pole is placed just off the center-left third, a syncopated vertical that keeps the road’s geometry from feeling mechanical. The composition reads instantly at room distance, which is why it remains memorable after a glance.

The Sky As Working Light

The enormous pale sky is not empty; it is an instrument. It creates a general, even illumination that dissolves hard shadows and makes surfaces turn by temperature rather than by theatrical contrast. Matisse scumbles the sky thinly so the weave participates, keeping the field lively and consistent with air. Near the top the white cools; near the horizon a faint warmth creeps in. This barely perceptible gradient persuades without storytelling; it is “felt weather.” Because the sky sets such a stable key, the ground can be simplified boldly without losing plausibility.

The Road: A Painted Conveyor Belt

The road’s broad wedge is a tour de force of reduction. It is not described with stones or ruts; it is described as a single, pale plane whose value and temperature carry the ascent. Near the viewer, Matisse cools the gray and thickens the paint slightly; nearer the village he warms and lightens it. Those adjustments alone suggest distance, a slight slope, and the chalky feel of rural pavement. Because the road occupies so much of the surface, its neutrality is crucial: it becomes the resting field against which small color events can sing.

Color Architecture: A Northern Chord With Sparing Accents

The palette is restrained—greens, earths, chalky whites, and a handful of moderated reds and blues—but every passage leans warm or cool. On the left bank, yellow-green grass moves toward olive in hollows; on the right, a deeper green shoulder slides into the shadow base of the house. The village roofs introduce the main warm accent, a brickish red that glows at low chroma against the pale sky and greens. The church mass is a blue-gray that ties the distance to the road’s cools. The telegraph pole reads as warm umber; the fence rail as a rhythm of darks that dance down the slope. Because Matisse avoids dead black, even the deepest seams keep chromatic life, which is why the painting feels airy rather than heavy.

Drawing Through Adjacency Rather Than Outline

Contours here are the consequence of neighboring tones meeting, not of lines drawn around things. The right façade is “drawn” where a warm, slightly darker wall meets the pale road; the left slope appears where green presses into gray; the steeple stands because a blue-gray wedge bites into the white sky. Where a line does appear—on the telegraph wire, a fence rail, or a roof seam—it is calligraphic and immediately reabsorbed into adjacent paint. This adjacency method keeps the surface unified and lets forms feel discovered rather than imposed.

Brushwork And The Feel Of Materials

Touch shifts with substance. The sky is scrubbed thin so air can enter. The road is brushed more opaquely, with long, even strokes that create a plane you could step on. The left slope is knitted from shorter strokes that change direction with the hill’s contours, a tactile analogue for grass. The house faces are laid in broader, flatter patches that read as plastered walls catching light. Tree crowns are flicked into place with rounded, stacked touches that refuse to count leaves yet convince as foliage. These changes in speed and viscosity give the picture its pulse.

Space Compressed Into A Decorative Field

Depth is believable, but the rectangle remains sovereign. The road narrows; the buildings shrink; colors compress toward blue as they recede; and yet the side masses press forward like screens, asserting the flatness of the design. This is the equilibrium Matisse sought: a scene you can walk into that still reads as an arrangement of shapes on a plane. The right-hand wall, for instance, feels simultaneously like the side of a building and like a large ochre-green tile anchoring the composition.

The Telegraph Pole And Wires: Modern Notes In A Rural Key

Matisse’s inclusion of the pole and wires does more than mark place; it adjusts rhythm. The vertical interrupts the easy glide of diagonals and sets up a counter-beat with the distant steeple. The thin wire lines arc across the pale sky like delicate drawing within the painting, the sole explicit linear element cutting the broad light. They also signal modernity—communication threading a traditional village—mirroring Matisse’s own modern thread running through a traditional genre.

Rhythm, Balance, And The Viewer’s Path

The painting teaches a route that mirrors walking. Your eye steps onto the pale road, follows its edges to the village, pauses at the steeple, then drifts left and right along the roofline before slipping back down the greens to the foreground corners. On each loop small correspondences register: the cool of the road echoed in the church mass, the warm brick repeated in a right-hand wall, the dark fence note answered by the shadow under the eaves. The picture becomes a circuit of equivalences rather than a set of items.

The Village As Human Scale And Social Space

No figures are shown, yet the hamlet carries human measure. Each building is a compact block of two or three tones; the roofs form a stepped phrase across the horizon; a narrow alley opens between right-hand walls; and a white facade glimmers on the left, set into the slope. These units are not anecdotes; they are rhythmic syllables. You sense the life—bells, doors, voices—without a single person painted. Matisse gives the social without the literal.

Dialogues With Tradition And Peers

“Lesquielles St Germain” converses with Corot’s economy and Cézanne’s constructive logic. From Corot and the Barbizon painters it borrows the dignity of subdued chords; from Cézanne it learns to build volume and recession with abutting planes. Yet Matisse’s temperament is distinct. Where Cézanne is analytic and pressurized, Matisse is harmonizing; where Impressionists might sparkle the road with light, he steadies it into a clarifying field; where academic naturalism would model each facade, he lets temperature shifts do the work. The result is modern without bravado.

Materiality And Likely Pigments

The harmony suggests a practical early-twentieth-century palette: lead white (perhaps tempered with zinc) for the sky and high values; yellow ochre, raw sienna, and Naples-like mixes for warm walls and grass tints; viridian or terre verte moderated by ochre and ultramarine for greens; ultramarine and cobalt for cool shadows and the church mass; raw and burnt umbers for posts, rails, and roof undernotes; a restrained vermilion or madder for brick accents; and ivory or bone black used sparingly to weight the darkest seams without killing chroma. Paint alternates between lean scumbles in the sky and fuller, buttery passages on the road and walls, creating a material counterpoint that your eye registers as different substances.

The Ethics Of Omission

One of the most modern features of the picture is what it declines to specify. There are no bricks counted, no shingles mapped, no windows detailed beyond a rectangle of tone, no stones on the road, no foliage painted leaf by leaf. The pole has no hardware; the steeple no architectural trivia. These omissions are not shortcuts; they are protections of the whole. By leaving out distractions, Matisse keeps attention on relations—where warm meets cool, where light meets plane, where big shapes balance. The painting stays readable from across a room and gains freshness at close range.

How To Look Slowly And Profitably

First let the three-part armature lock in your mind: pale sky, pale road, flanking masses of green and wall. Then approach. Watch edges appear by adjacency—the crisp meeting of ochre wall and gray road, the soft melt of tree crown into sky, the blue-gray steeple biting into the white. Track temperature shifts across single planes, like the right façade warming near the ground and cooling toward the roofline. Step back again until the scene holds in one breath as a poised funnel of space. Repeat that near–far oscillation, and the painting reveals itself as a network of tuned adjustments rather than a fixed view.

Place Within Matisse’s 1903 Arc

Seen alongside his river scenes and studio interiors of the same year, “Lesquielles St Germain” clarifies what Matisse was teaching himself. He was learning to reduce a motif to a few governing shapes, to let a high-key sky set the entire climate, to model through temperature instead of heavy shading, and to keep depth persuasive while preserving the surface as a designed field. Within two years he would increase chroma dramatically; these structural lessons are what allow those later colors to feel serenely inevitable rather than sensational.

Enduring Significance

The painting endures because it turns an ordinary approach road into a durable harmony. It gives you the felt experience of arrival—quiet ascent, airiness overhead, the pull of a steeple—while remaining a confident orchestration of planes and tones. It demonstrates that modernity in Matisse is as much about disciplined relation as it is about color bravura. The telegraph wire, the trimmed façades, the broad road and breathing sky all say the same thing: simplify, balance, tune. The world will recognize itself in that clarity.