Image source: wikiart.org

A Fresh Look at “Laurette’s Head with a Coffee Cup” (1917)

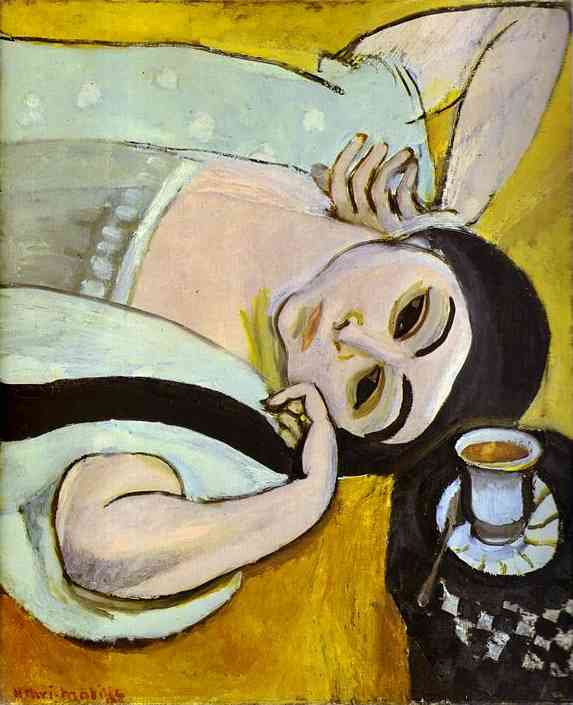

Henri Matisse’s “Laurette’s Head with a Coffee Cup” captures a moment of intimate repose that is also a rigorous formal experiment. Painted in 1917, the work presents Laurette reclining across a yellow tabletop, her cheek resting on her forearm while a small white cup and saucer quietly occupies the corner. The pose is unconventional, the viewpoint tilted, the palette at once restrained and radiant. The painting compresses domestic calm and audacious design into a single field, revealing how Matisse could make a simple everyday scene feel monumental through clarity of line, orchestration of color, and the courage to crop and rotate space. It is a quintessential work from a hinge year in his career, bridging the disciplined simplifications of the mid-1910s and the luminous sensuality of the Nice period that would begin almost immediately afterward.

The Year 1917 and a Career at the Threshold

Understanding the context of 1917 illuminates the painting’s mix of intimacy and structure. Matisse had already shocked Paris with the blazing color of Fauvism a decade earlier. By the mid-1910s he was testing a more pared-down language: fewer colors, stronger contours, and a search for equilibrium between observation and abstraction. “Laurette’s Head with a Coffee Cup” belongs to the final months before his move to Nice, where airy interiors and patterned textiles would flood his canvases. Here, he chooses a reduced stage—one model, a tabletop, a solitary cup—yet achieves a complex orchestration that anticipates the Mediterranean serenity to come. The picture feels like a rehearsal for his later interiors, but also like a summation of lessons learned from Ingres’s contour, Cézanne’s planes, and his own fauvist insistence on color as structure.

Laurette as Muse and Motif

Laurette (often recorded as Lorette) was a frequent model for Matisse in 1916–1917, appearing in robes, in patterned dresses, seated, reclining, and shown in closely cropped portraits. She was less a biographical subject than a flexible set of forms—almond eyes, strong brows, sleek black hair—that Matisse could vary to study rhythm, volume, and the expressive power of black. In this painting, Laurette’s body is barely present beyond her arms and shoulders; the face becomes the primary site of attention, while the coffee cup provides a counter-motif, a small chorus echoing the oval of the head. The model’s languor is echoed by the tabletop’s broad plane, and her half-closed eyes suggest the suspended time of daydreaming, or the hush that follows a quiet conversation. Laurette is both person and pattern; she grounds the composition and simultaneously releases it into abstraction.

Composition on a Tilt

The first sensation the painting delivers is its rotation. Matisse tilts the scene so that Laurette lies diagonally from lower left to upper right, while the tabletop reads as a slanted yellow field. This simple decision transforms an ordinary moment into an audacious spatial proposition. Gravity seems softly suspended; the gaze slides along the diagonal of the forearm to the almond eyes, then drops to the coffee cup poised on its saucer. The arm forms a sweeping curve that braces the head; the opposite hand tucks behind an ear in a small cascade of fingers that echo the cup’s handle. The diagonal movement lends the painting motion without spectacle, a sense of drifting rather than falling. The raised forearm near the top edge creates a visual ceiling, containing the figure within the tabletop’s warm plane and preventing the eye from wandering out of the frame.

The Quiet Drama of the Coffee Cup

The modest cup and saucer might seem like a prop, yet they are crucial to the painting’s architecture. Their firm white ellipse punctuates the lower right, counterbalancing the pale ovals of cheek and shoulder on the left. The black-and-white pattern beneath the saucer adds a rhythmic check that answers the soft dots on Laurette’s dress. The spoon, angled slightly, repeats the diagonal motion of the arm. Matisse often used a small object to anchor a composition—fruit on a table, a vase, a violin. Here the cup functions as a hinge between still life and figure, domestic object and human presence. It shifts the painting from portrait to interior, pushing it into that fertile hybrid in which Matisse excelled. It also lends temporal specificity. A cup implies a pause, a break in activity, the interval that opens when one sits to sip and think. The painting becomes a picture of interval, and the interval becomes a stage for form.

A Palette of Warm Air and Cool Restraint

Color is held in perfect tension between restraint and glow. The yellow tabletop is not a single note but a field of modulated ochres that carry light across the surface; it is the atmosphere in which the figure rests. Laurette’s skin is a structure of cool lavenders, soft grays, and warm peaches that shift with purposeful economy. Her dress is a pale mint, flecked with small dots that are less pattern than breath marks, a gentle cooling of the composition’s heat. Black appears along the hair, sleeve, and the textile under the cup, acting as both contour and positive color. The white of the cup and portions of garment are never sterile; they are warmed by surrounding tones and broken by blue-gray halftones that keep them in harmony with the whole. The result is a chord: yellow’s warmth, black’s firmness, skin’s delicate violets, and a whisper of green all sounding together without clamor.

Black as Structure and Light

Matisse treats black as a luminous substance. The hair mass near the lower left reads not as vacancy but as polished matter, its surface described by long loaded strokes that catch light on their ridges. The black sleeve slices the mint garment with a confident arc, repeating the hair’s weight and subtly tightening the composition like a belt. Under the cup, a black and white check pattern creates the strongest value contrast in the painting, but even there the black is alive with slight tonal variations, so the area feels woven rather than painted flat. In the features, thin black lines articulate eyelids and brows, and bolder touches define the nostrils and lip curve. These marks serve as a musical score for the gaze, telling it where to pause and where to resume. Black does not outline; it conducts.

Brushwork and the Truth of the Stroke

The surface is frank about its making. In the tabletop one sees the brush drag and change direction, revealing how the field was built in layered sweeps. The garment’s mint passages show thin, slightly dry paint where the bristles leave troughs, which enliven areas that might otherwise turn static. Flesh is modeled with broader strokes, the transitions between tones allowed to remain legible rather than fused into anonymous smoothness. The cup and saucer are pared down to essential curves and planes, but their edges are not mechanically sharp; they are painted edges, living edges. This visibility of facture is not a boast but a guarantee of freshness. It lets the viewer feel the time of painting, the speed of the wrist, the pauses between strokes. The scene’s sense of rest is paradoxically built from the energy of the marks that created it.

Space as a Shallow Stage

The painting achieves depth without conventional perspective. The tabletop tilts up like a stage; the figure lies across it like a relief sculpture resting on a horizontal plane. The coffee cup anchors a near corner, but the background provides no window into complex space. Everything happens near the surface. This shallow architecture intensifies the design, ensuring that every shape plays a role in the whole. The oval of Laurette’s face corresponds to the oval of the saucer; the diagonal of the forearm responds to the angled spoon; the sweep of the black sleeve counters the lighter curve of the shoulder. The eye reads these interrelations as a network rather than as a tunnel. This is a portrait that asks to be read frontally, not entered like a room. The shallow stage also amplifies serenity: the world has been pared down to tabletop, figure, and cup, a space large enough to breathe but small enough to feel complete.

The Role of Gesture and Pose

Laurette’s gesture is everything. One hand cradles the face with a touch that is both intimate and architectural; it literally supports the head while architecturally anchoring the composition. The other hand hooks behind the ear in a small flourish, its splayed fingers echoing the scalloped edge of the sleeve. The pose has no theatrical gesture and no strain, yet it holds a tension between wakefulness and drift. The eyes, elongated and heavy-lidded, meet the viewer with soft firmness. The mouth is drawn with the economy of two arcs and a small central notch. No extraneous detail distracts. The portrait’s mood arises from this economy: a private interval of thought, small and sufficient to itself.

Pattern, Repetition, and Visual Music

Matisse uses pattern sparingly and meaningfully. The polka dots of the dress are more like a rhythm of breath than a textile design. The check beneath the saucer is a sharper rhythm, a syncopation that answers the dots with percussive beats. Repetition binds the composition: ovals echo in head, shoulder, cup, and saucer; diagonals recur in arm, spoon, and the tilt of the composition itself. These repetitions act like a harmonic progression in music, unifying disparate motifs into a coherent movement. The eye experiences the picture as a score it can read again and again, discovering new correspondences each time.

Conversation with Tradition

Though modern in its cropping and spatial tilt, the painting speaks fluently with tradition. The dignity of contour and the belief that line can confer character recall Ingres. The construction of the head from frank planes owes something to Cézanne’s insistence on form over detail. The flattened tabletop and audacity of the angle nod toward Japanese woodblock prints, which Matisse collected and admired. Yet none of these sources dominate; they are metabolized into a language that is unmistakably his own. The cup, an inheritor of centuries of still-life painting, becomes a modern sign not because it is new but because it is used with new clarity.

Intimacy Without Anecdote

Many portraits rely on anecdotal cues to build intimacy—books, flowers, room furnishings. Matisse removes such props, leaving a single household object that intensifies rather than distracts. The painting is intimate precisely because it is so focused. One sitter, one tabletop, one cup: the world trimmed to essentials. From this spareness emerges a tenderness free of sentimentality. The tender feeling comes not from narrative but from the way colors lean toward each other, from the way a line curves to cradle a cheek, from the way black supports white like a partner in a dance. It is intimacy built from syntax rather than story.

The Coffee Cup as Modern Life

The cup also places the portrait in modern time without trumpeting modernity. Coffee implies café culture, routine, pause, and wakefulness; it belongs to the twentieth-century city as surely as to the private home. By including it, Matisse silently ties Laurette to the everyday rituals of his moment. But the object remains small and humble, refusing to pull the painting toward anecdote or social commentary. It carries the light of the corner it occupies, a bright punctuation that brings the diagonal composition to rest.

Anticipations of the Nice Period

Soon after this painting, Matisse would begin the Nice years, where leisure, interiors, and patterned sense memory would dominate his canvases. The warmth of yellow here foreshadows Mediterranean light; the attention to fabric edges and to the sensuality of repose foreshadows the odalisques and studio models he would paint with windows open to sea air. Yet the restraint of drawing and the frankness of line tether the painting to the earlier, more austere experiments. In this way, “Laurette’s Head with a Coffee Cup” becomes a hinge: it sings in a key that belongs to both the later and the earlier Matisse, a chord sustained between two periods.

Material Presence and the Visibility of Making

The work’s material presence anchors its authority. One senses the weight of oil paint, the way thin layers on the tabletop allow previous tones to whisper through, the density of the hair passages where the brush was loaded and pulled in a single breath, the slight roughness at edges where wet met drying. The signature tucked near the lower edge is not a flourish but a final note in a careful cadence. Seeing these material traces is part of the viewing experience; the painting does not hide how it came into being. That honesty reinforces the calm of the image, assuring viewers that its serenity is earned rather than manufactured.

Why the Painting Feels Contemporary

Despite its date, the painting feels contemporary because of its graphic immediacy, cinematic cropping, and the unapologetic legibility of its marks. The diagonal framing could be a film still; the reduction to a few resonant colors aligns with modern design; the frank brushwork matches a contemporary appetite for surfaces that show their history. It looks modern not because of novelty but because it distills experience into terms that remain legible and fresh a century later: the pause of a coffee break, the tilt of a head in thought, the sun-washed table where time slows.

Enduring Significance

“Laurette’s Head with a Coffee Cup” condenses Matisse’s deepest commitments—balance, purity, serenity—into a domestic scene that achieves monumentality without size. It demonstrates how boldness can arise from limits: a short palette, a small number of forms, a deliberate tilt that reimagines space. The painting teaches the pleasure of looking slowly, of noticing how the oval of a cup can hold its own against the oval of a human face, how a single black sleeve can anchor a whole field of color, how a diagonal can make rest feel like motion. It belongs among the strongest statements of Matisse’s portrait-interior hybrids and continues to reward sustained attention with the revelation of new harmonies.

Conclusion

Henri Matisse transforms a quiet interval at a table into an enduring meditation on form. Laurette, lost in suspended thought, becomes the axis of a composition where color breathes, line sings, and objects carry meaning beyond their scale. The cup keeps time, the arm draws a path, the face invites contemplation. Nothing is superfluous, and everything is alive. In its calm authority, “Laurette’s Head with a Coffee Cup” shows how an artist at a turning point could find a language capacious enough to hold both experiment and ease, both discipline and delight. The viewer comes away with the sensation of a pause that extends beyond the edges of the canvas, a pause in which the ordinary becomes inexhaustible.