Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction to “Laurette with Long Locks” (1917)

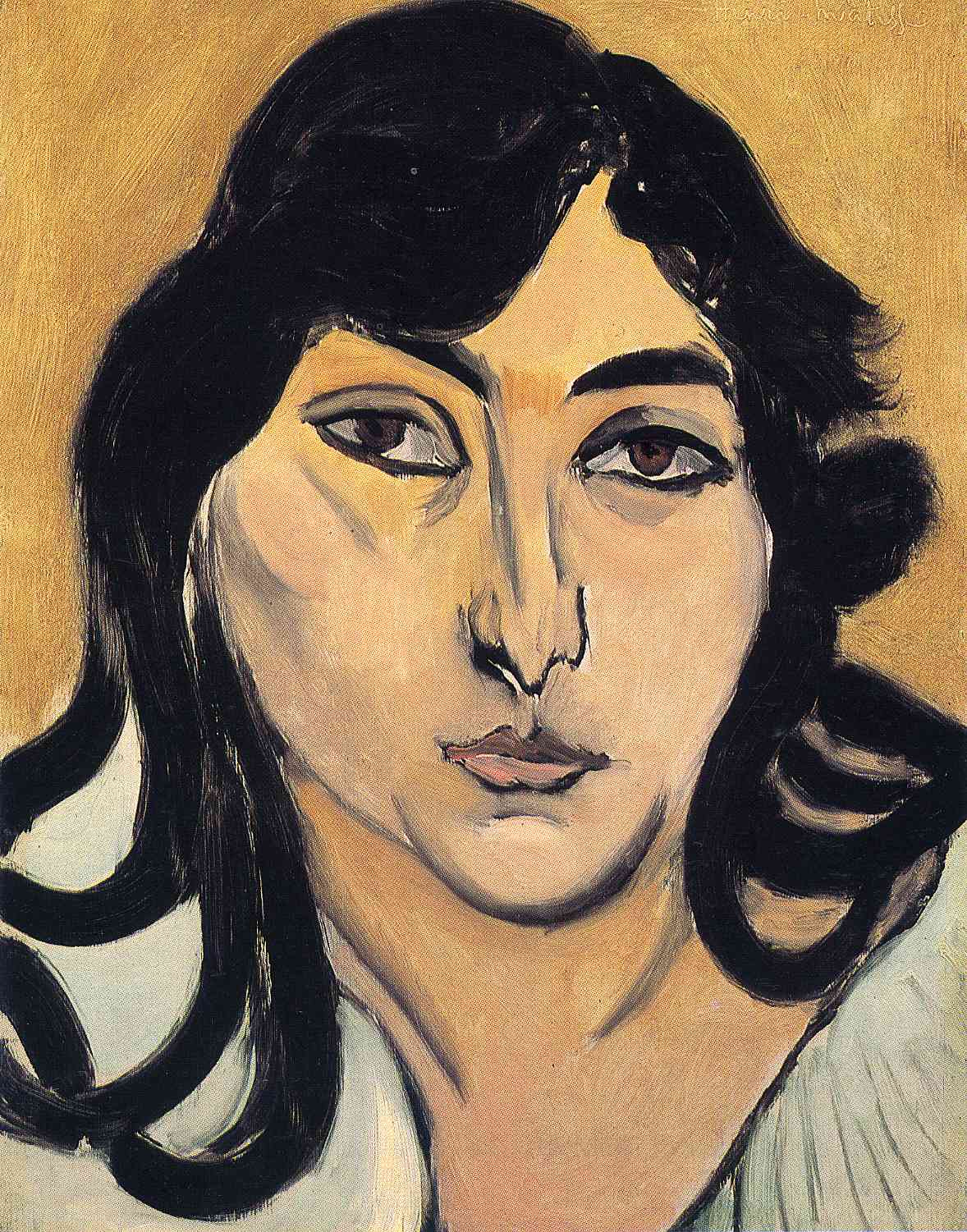

Henri Matisse’s “Laurette with Long Locks” is a concentrated study in presence, economy, and line. Painted in 1917, it shows the artist’s favored model Laurette in an extreme close-up that all but eliminates context. The head fills the surface, framed by inky waves of hair that give the portrait its title. At first sight the picture reads as disarmingly simple: a warm ochre ground, a pale garment, a face held within a mass of black locks. Yet the longer one looks, the more finely tuned its orchestration becomes. The painting captures a pivotal moment in Matisse’s development, when the fauvist blaze of pure color had cooled into a language of deliberate restraint and when his attention to clarity and balance was about to usher in the luminous Nice period. “Laurette with Long Locks” fuses these directions in a portrait that is both frank and monumental, both intimate and architecturally composed.

The Historical Moment and Matisse’s Turning Point

The year 1917 marks a hinge in Matisse’s career. The shock of Fauvism in the first decade of the century had placed color at the center of his art. In the years following, he explored a more pared-down grammar of forms that nonetheless retained the vitality of color, often pursuing a disciplined simplicity in which every mark counted. Around 1917 he was preparing to leave the northern light for the Mediterranean glow of Nice, where he would paint a series of interiors and odalisques saturated with air and pattern. “Laurette with Long Locks” stands at this threshold. Its limited palette and emphatic drawing acknowledge the austere experiments of the mid-1910s, while its tactile attention to hair, skin, and the gentle warmth of the background anticipates the sensuous atmosphere of the work to come. Understanding this painting as a transition clarifies why it seems both severe and tender at once.

Laurette as Model and Motif

Laurette, sometimes recorded as Lorette, appears across numerous canvases Matisse produced in 1916 and 1917. She is the protagonist of a small universe within his oeuvre: robed in green, draped in patterned cloth, reclining, seated, or shown as here in head-and-shoulders view. Matisse was not cataloguing personalities so much as exploring a set of visual problems through a sitter whose features and bearing allowed for elastic interpretation. Laurette’s almond eyes, firm brow, long oval face, and raven hair offered strong shapes that could be compressed or expanded, accented or softened as the composition required. In “Laurette with Long Locks,” he distills those signatures into a face that becomes almost emblematic, an iconic presence that gives the painter a testing ground for line, contour, and the expressive potential of black.

Composition by Compression

One of the first things viewers feel is the pressure of the image against the edges of the canvas. The head is cropped close on all sides. Shoulders and garment barely enter before the frame cuts them off, leaving a shallow triangular opening at the bottom. This compression accomplishes several things at once. It transforms the head into an object with the weight of a carved relief, flattens space so the surface reads as a coherent field, and intensifies attention on essential relationships: the tilt of the eyes, the descent of the nose, the poised closure of the lips. The composition creates a dance of verticals and curves. A central axis runs from the hair’s part down through the nose to the mouth, stabilizing the face like a spine. On each side, black locks arc in counter-rhythms that soften the strictness of that axis. The controlled opposition between straight and curved, between centered symmetry and slight asymmetry, keeps the portrait alive without pushing it into restlessness.

The Palette of Deliberate Restraint

Although Matisse is celebrated for chromatic audacity, the color in this painting is held in reserve. The background’s ochre is warm, earthy, and thinly brushed so that subtle variations in tone carry the light. The flesh is set in creams, warm grays, and muted peach, with spare violets and cool half-tones around the eyes and lips. The garment is a pale, almost chalky greenish white that quiets the bottom portion of the composition. Black dominates the hair and is reiterated as a sculpting agent in the eyebrows, eyelids, and nostrils. The limited range magnifies the effect of each hue. A small rose note in the lower lip becomes eloquent precisely because so few bright colors compete with it. The painting demonstrates Matisse’s conviction that intensity can arise not only from saturation but from contrast and placement. The warm ground plays against the cool garment; the fleshtones vibrate between them; the black both anchors and illuminates.

Black as a Luminous Color

Matisse famously treated black as a color that can hold and emit light rather than simply absorb it. In “Laurette with Long Locks,” black is structural and affirmative. The hair is painted in long, calligraphic sweeps that are glossy in places and matte in others, catching the light on edges and ridges so that the locks feel elastic and alive. Within those strokes, tiny intervals of the warm ground peep through like glints, turning what could be a flat mass into a living surface. The same positive black sharpens the eyes and nose. A thin black contour underlines the right eyelid; a thicker passage strengthens the brow’s arc; brief, clipped marks articulate the nostrils. None of these lines are descriptive in a photographic sense. They function instead like musical cues that shape rhythm and emphasis. The effect is clarity without harshness, firmness without rigidity.

The Poetics of Brushwork

The portrait’s power depends on the honesty of its strokes. In the cheeks and forehead, Matisse uses broad, unbroken passages of paint that seem to have been laid in decisively and left to stand. The surface in these areas is quiet, its direction slight and slow, conveying a sense of breath beneath the skin. Around the eyes and mouth the rhythm accelerates into small, precise touches, still economical but more animated. The hair becomes the most obviously calligraphic zone: long arcs, loaded and pulled, curve and taper with a writer’s confidence. The succession of tempos—calm planes of flesh, quick articulations of features, flamboyant arcs of hair—gives the painting its inner beat. The viewer reads the surface not just as representation but as the record of an encounter between eye, hand, and subject.

Cropping, Monumentality, and the Mask

Because the head is so near and the background so reduced, the face takes on a mask-like authority. This is not to say the portrait is impersonal. Rather, Matisse harnesses the abstract qualities of a mask—frontal clarity, simplified planes, and commanding presence—to magnify the sitter’s impact. The nose is reduced to a firm ridge with flanking shadows; the eyes are almond shapes whose whites are almost gray; the mouth is a set of two carefully drawn arcs. From these few elements a personality emerges. The monumental face feels at once intimate and impassive, a paradox sustained by the tight crop and the unwavering frontal gaze. That duality between person and icon is a recurring ambition in Matisse’s portraiture, and this canvas achieves it with uncommon concentration.

Facial Structure as Interlocking Planes

Matisse constructs the face as a system of planes rather than a mosaic of details. The left cheek turns with a single gradient from light to midtone, while the right cheek sits in slightly deeper value to suggest a gentle cast shadow. The bridge of the nose forms a narrow vertical plane that flares at the tip, where a few darker touches indicate nostrils and a sharp turning edge. The upper lip is modeled with a delicate cool notch at its center and a warm highlight along its rim; the lower lip receives a modest accent to keep it from dominating. The eyelids are heavier than in many Matisse portraits, a choice that slows the gaze and contributes to the sitter’s inwardness. These decisions generate a believable head with remarkably few ingredients. The result is a face that holds together from across a room yet rewards close viewing with the subtleties of its modeling.

The Background as Active Atmosphere

Although it remains unobtrusive, the ochre ground plays an indispensable role. Thinly painted in translucent layers, it breathes as a field rather than as a wall. Slight swirls and shifts in tone create an atmospheric pressure around the head, preventing the figure from floating. At several points the hair blends into this ground in soft, interleaved edges, creating the impression of a halo without resorting to literal luminosity. The background’s warmth envelops Laurette, softening the austerity of the composition and lending the whole a tempered radiance.

The Gaze and the Question of Psychology

Matisse was less interested in psychological storytelling than in the equilibrium of forms, yet his portraits often carry a quiet emotional charge. The gaze here is direct but not confrontational. Heavy lids and a minute deflection in the direction of the pupils produce an impression of self-containment, as if the sitter were allowing herself to be seen without entirely yielding her interior life. The closed mouth reinforces that sense of poise and reserve. The absence of narrative props—no jewelry, patterned textiles, or studio furnishings—frees the viewer from anecdote and returns attention to the visual terms themselves. What one senses as personality emerges from the orchestration of lines, planes, and tones rather than from external signs.

Dialogue with Artistic Traditions

Matisse’s modernism often works through tradition rather than against it. The presence and dignity of contour recall Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, whose drawing Matisse admired for its ability to confer elegance with economical means. The structural logic of the head, built from large interlocking planes, reveals his long study of Paul Cézanne. The mask-like frontality and concentrated simplification show his engagement with non-Western sculpture and with Japanese prints, where bold silhouette and decisive line carry much of the expressive burden. “Laurette with Long Locks” synthesizes these influences in a way that feels neither eclectic nor derivative. It is unmistakably Matisse, yet it carries the wisdom of the artists he revered.

Relationship to the Laurette Series

Comparing this canvas with other Laurette portraits underscores its special character. In several related works from 1916–1917, the model appears in patterned robes or interiors, her body more fully described, the palette more varied. In this painting, Matisse strips away pattern and pose to test a different premise: how much can be reduced before a portrait loses its human spark. The answer, here, is that very little is needed when the components are tuned to one another with precision. The face, hair, and ground interlock so elegantly that the picture achieves a serenity the more decorative Laurettes sometimes trade for opulence. As a result, “Laurette with Long Locks” reads as the series’ most concentrated statement.

Material Choices and the Visibility of Making

The work’s material presence is essential to its meaning. Matisse lets the weave of the canvas and the drag of the brush remain visible. Thin paint in the background exposes ground tones beneath, giving it a slightly abraded, breathable quality. Thicker, oil-rich strokes in the hair sit on top like ribbons, catching the light and declaring their facture. The transitions in the flesh are often achieved by crossing wet strokes lightly rather than by smearing, so the directionality of the brush persists even in soft passages. These choices refuse finish in the academic sense, substituting instead a truthfulness to process. The surface tells the viewer how the image was built, and that openness becomes part of the portrait’s appeal.

Balance, Purity, and the Ethic of Simplification

Matisse famously spoke of seeking balance, purity, and serenity. Those aims should not be confused with blandness. In this painting they are reached by pruning anything inessential. There is no highlight that does not serve form, no contour that does not serve structure, no color that does not serve harmony. Simplification is not an abdication of complexity but a different form of it, moving from the complexity of information to the complexity of relations. The viewer experiences that clarity as calm. The portrait registers as measured and inevitable, the way a perfectly weighted sentence or chord feels inevitable once sounded.

Anticipations of the Nice Period

Within months of 1917, Matisse would establish himself in Nice and bring new attention to light-soaked interiors, patterned screens, and languid models. The seeds are present here. The picture cultivates warmth without noise, sensuality without excess. The hair’s glossy abundance foreshadows the luxuriant draperies and textiles to come, even as the discipline of the drawing preserves the severity of the preceding years. The painting can thus be read as a bridge: last statement of an ascetic impulse, first whisper of Mediterranean softness.

The Role of Hair as Architecture

The title focuses attention on hair, and Matisse treats it as more than ornament. The locks are load-bearing elements in the design, bracketing the face and establishing the largest darks in the composition. Their looping shapes echo across both sides, creating a counter-chorus to the face’s vertical spine. By staging the strongest value contrasts at the edges, Matisse allows the central planes of the face to remain relatively unmodeled yet still volumetric. The hair, in short, builds the portrait’s architecture. Without it the face would lose both its clarity and its grandeur.

The Experience of Looking

Standing before the painting, viewers may notice a rhythmic shift as their eyes move from feature to feature. The broad left cheek slows the eye; the ridge of the nose guides it down; the lips pause it briefly; the hair accelerates it outward along rolling arcs before returning to the center. That circulation, gentle but insistent, makes the picture feel complete. The head is not an isolated object floating in silence but the hub of a visual system that breathes. This quality of completeness, of a closed yet lively structure, is part of what gives the portrait its meditative character.

Legacy and Significance within Matisse’s Oeuvre

“Laurette with Long Locks” stands out as one of Matisse’s most distilled portraits. It shows how a revolutionary in color could, when the moment required, express force through limits. The canvas becomes a primer in how to do more with less: fewer colors, fewer details, fewer lines, but a stronger whole. Later generations of painters—whether pursuing figuration with economy or abstraction with human touch—have found in such works a model of decisiveness and clarity. The portrait exemplifies Matisse’s broader achievement: to make art that feels inevitable without feeling predictable, serene without being static.

Why the Painting Feels Contemporary

Despite its date, the painting reads as contemporary because it privileges graphic immediacy, tight cropping, and material frankness—features that align with modern photography and design. The extreme close-up anticipates cinematic framing. The affirmation of black as a positive, shining presence resonates with graphic arts and fashion illustration. The legible brushwork honors making at a time when viewers value authenticity of process. These affinities help explain why “Laurette with Long Locks” remains compelling to present-day audiences who may not know the surrounding history yet instinctively recognize the portrait’s clarity and poise.

Concluding Reflections

Henri Matisse’s “Laurette with Long Locks” is a portrait of concentrated authority. It compresses the head against the surface to create monumentality without pomp. It builds a face from a minimum of tones and a maximum of purpose. It turns hair into architecture, black into light, and a model into an emblem of balance. As a document of 1917, it records a master at a crossroads; as a painting, it requires no context to communicate its power. The viewer leaves with the imprint of Laurette’s gaze and with the memory of strokes that are as honest as they are elegant. In that union of frankness and grace lies the enduring power of this picture.