Image source: wikiart.org

A Coastal Vision Anchored by a Modest Still Life

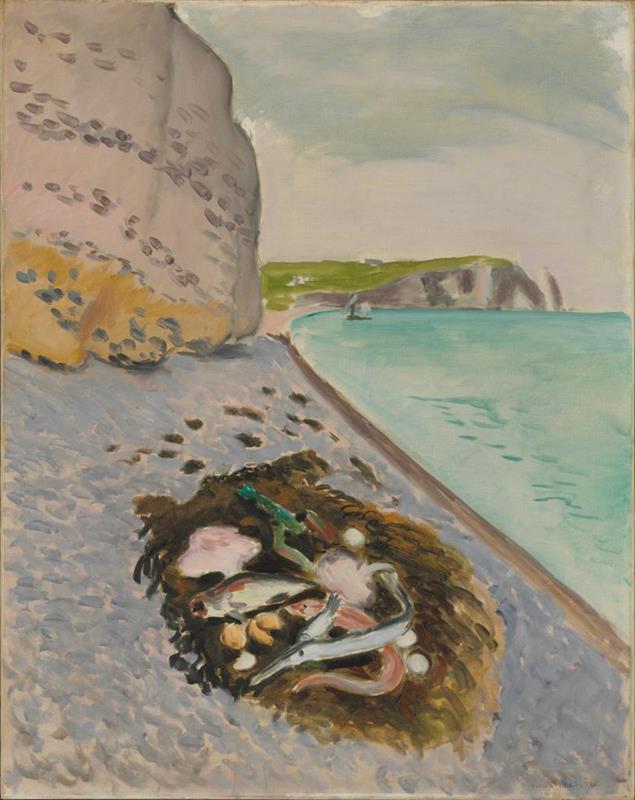

Henri Matisse’s “Large Cliff with Fish” (1920) unites two genres he knew intimately—landscape and still life—into a single, disarmingly simple image. At first glance, the painting reads as a broad coastal view: a chalky cliff presses in from the left, a ribbon of pebbled shore sweeps diagonally toward a turquoise sea, and beyond, pale headlands dissolve into a luminous horizon. Yet what fixes the eye is not the promontory or the water but a small heap of seaweed and fish lying in the foreground. Matisse builds the entire composition around this humble mound, using it as a weight that pulls the viewer into the scene and then sends the gaze skimming outward along the beach and over the water. The result is a picture that feels both monumental and intimate, geological and domestic, a meeting of stone’s permanence and the day’s catch—briefly vivid, soon to vanish.

Where and When: Étretat After the War

Painted in 1920, the work belongs to a moment when Matisse, having weathered the upheavals of the First World War, pursued a new clarity of form and light. He made a series of coastal canvases at Normandy’s Étretat, a site famous for its sheer white cliffs and curving bays. The location mattered for more than its beauty. Étretat’s cliffs had already been imprinted in art by Courbet and Monet, and by coming here Matisse stepped into a lineage of modern French painting while deliberately redefining it. Instead of Monet’s shimmering atmospherics or Courbet’s crashing surf, Matisse offers quiet weather and a tideline strewn with life. The landscape becomes a backdrop for a grounded, tactile meditation on looking and arranging, the kind of reflection that guided much of his work in the 1920s.

Composition as a System of Forces

The painting’s structure is simple yet decisively engineered. The cliff on the left is a blunt vertical mass that nearly grazes the top edge, a block of pale ochres and violets that asserts the canvas’s flatness even as it implies immense weight. Opposing that mass is the calm expanse of water on the right, a horizontal field softened by thin, transparent paint. Between these poles unspools a single dominant diagonal: the shoreline that begins near the fish heap and leads to the far headlands. Matisse’s diagonal is not a flourish; it is a conveyor of attention. It carries the viewer from the foreground to the far distance and back again, orchestrating the rhythm of the painting without theatrics.

This arrangement turns the foreground still life into a compositional hub. It sits slightly left of center, precisely where the diagonal begins, and its oval of seaweed acts like a dark lens. From there, the small flecks of pebbles, the trail of darker stones, and the pale strip where beach meets water all reinforce a sense of motion. The eye circles the fish, slides along the shore, pauses at the headland silhouette, glances at the matte sky, and returns to the near pile of forms—an elegant circuit designed through spareness rather than density.

Scale and the Poetics of Near and Far

One striking effect of the painting is its sense of scale: the cliff looms, the water spreads, the headlands recede into mist, and then, very close to us, lies the quotidian matter of food. Matisse insists that near and far belong to one visual sentence. He resists the grandiose by tethering it to the ordinary. The fish heap, rendered with quick, supple strokes, is not a token of genre but a tool of measure—its recognizable size calibrates the distances elsewhere in the picture. A leaf of seaweed or the glint of a fish eye becomes a miniature unit against which the enormous cliff gains legibility.

This oscillation between intimacy and landscape lends the piece its emotional climate. The closeness of the still life invites sensations a photograph cannot carry: the smell of brine, the grit of pebbles underfoot, the dampness that darkens seaweed. In contrast, the sea and sky are flattened to broad areas, distant, impersonal, silent. Matisse’s staging implies a continuum: nature’s monumentality and the precarious, daily harvest of those who live beside it.

Color as Atmosphere and Economy

Although Matisse had been the herald of Fauvism’s fierce chroma fifteen years earlier, here his color is deliberate and economical. He restricts himself to a suite of chalky hues—bluish grays for the pebbles, milky aquas for the water, a faint citron and lavender for the cliff, small accents of pinks and creams in the fish. The palette is coastal but not literalist: rather than cataloging a beach’s tones, he reduces them to a set of relations that feel inevitable. The sea’s green is softened by white, as if light were dissolved into pigment. The cliff’s warmth, tinged with violet shadow, keeps the left side from ossifying. And the fish introduce the brightest notes, though even they are tempered, preventing the foreground from rupturing the picture’s calm.

By muting saturation and letting the ground show through in places, Matisse compresses light into surface. The painting glows not because it is filled with bright hues but because the values are delicately stepped, allowing the eye to register light as a presence that binds forms together. The sky’s thin veil of paint, slightly cool and gray, is particularly telling: it reads as maritime haze, the kind of day without spectacle that painters often avoid and that Matisse welcomes.

Brushwork, Edges, and the Craft of Seeing

Matisse’s handling here is confident yet relaxed. The cliff face displays a mosaic of marks—the scattered gray ellipses that suggest embedded stones, the pale washes that articulate planes, the frayed edges where rock meets air. On the pebbled beach he keeps the touch soft and summary, knowing that to stipple would deaden the surface. The most calligraphic passages appear in the still life: a long, snapping stroke limns the curve of a fish; a quick loop locates an eye; a dragged, broken brush mixes brown, green, and black into seaweed. These marks embody the painter’s double ambition—to construct a persuasive scene and to leave the viewer aware of paint’s physicality.

Edges do much of the narrative work. The cliff’s contour is blunt and heavy; the waterline is a slender ribbon of tone that trembles without fuss; the far headlands are softened to a vaporous band, a few calm bends of the brush. Each edge tells us how to feel the object it bounds—solid, slippery, receding. Through this vocabulary of edges, Matisse reveals what he always sought: to translate the sensation of looking into a coherent surface without sacrificing sensation to description.

The Still Life on the Strand

Why place a still life on the shore? Matisse’s decision is not simply anecdotal. Fishermen commonly sort, gut, or display their catch on the beach; such a scene would not have felt staged to a local eye. Yet the pile is also a painter’s invention, an outdoor echo of the tabletop arrangements that filled his studio. In interior still lifes, the table’s edge is the stable line anchoring fruits and vessels; here, the shoreline takes that role, and the oval of seaweed substitutes for a platter. The fish themselves introduce sleek ellipses that rhyme with the pebbles scattered around them.

Thematically, the still life intensifies the painting’s meditations on time. The cliff represents geologic duration; the sea, cyclical motion; the fish, immediate perishability. By juxtaposing these, Matisse casts the picture as a gentle vanitas. There is no skull, no candle guttering in a draft, yet the forms carry the idea of briefness. The fish will soon spoil; the tide will wash away the marks beside them; the cliff endures and erodes over centuries. The painting registers these temporal scales without rhetoric, trusting the viewer to feel them.

Dialogue with Precedents: Courbet, Monet, and Chardin

Matisse’s coastal choice inevitably summons Courbet’s stormy seascapes and Monet’s Étretat en plein air studies, but his mood is more meditative. Courbet’s waves are events; Monet’s light is a continuous variable; Matisse’s emphasis is the thought of composition itself. If there is an older kinship, it is with Chardin’s still lifes, whose restraint and moral quiet Matisse long admired. In the fish pile, one senses a Chardinian tenderness for ordinary things, rendered without fuss and invested with dignity.

By welding that tenderness to a resolutely modern landscape structure, Matisse updates tradition. He declines both the anecdotal romance of a fisherman’s life and the purely optical thrill of light on water. Instead, he places the practice of painting—arranging, balancing, feeling one’s way through color and edge—at the center, using the motif to think aloud.

The 1920s Turn: Clarity After Fauvism

“Large Cliff with Fish” illustrates a broader turn in Matisse’s work during the late 1910s and early 1920s. The earlier explosions of Fauve color had given way to a language concerned with stability, armature, and calm. He pursued what he sometimes called “a state of condensation” in which a few relationships carry the whole image. The beach scene, with its restricted palette and sparse notations, epitomizes this condensation. It is neither austere nor decorative; it is full, but with essentials. The economy here is not a retreat from ambition; it is ambition refined, a demonstration that sensation can survive simplification.

Space Without Illusionism

Despite the clear recession from foreground fish to distant promontory, the painting keeps reminding us that it is a flat object. Matisse underscores the picture plane in several ways: the cliff’s contour presses against the canvas edge; the band of sea is painted as a sheet; the sky is a thin, brushed veil. Depth is present but moderated, like a chord voiced to avoid dominance by any single note. This balance—space without theatrical illusion—is part of Matisse’s larger project to free painting from mimetic obligation while retaining its contact with the world.

Weather, Season, and the Tone of the Day

The day Matisse evokes is ordinary coastal weather—no spectacular sunset, no foaming storm. The light is cool and dispersed, the kind that makes edges soft and colors milky. Such weather is artistically strategic: it allows the painter to choose what to emphasize, unpressured by dramatic contrasts. The quiet consistent light also links the far distances with the near pile of fish, so the painting reads as one environment rather than a stage with spotlighted actors. The feeling is contemplative rather than ecstatic, a mood of receptivity in which seeing is a form of breathing.

The Human Presence Without Figures

No people appear, yet their presence is everywhere. Someone carried these fish, arranged them, left traces of steps on the pebbles. A boat slips along the far waterline; the cut of the distant cliff suggests paths worn by work. Matisse often found ways to imply human life without depicting it directly, and here he uses objects as proxies. The effect is to grant the viewer an unoccupied vantage, as if one had just approached the heap and paused to look up and out, briefly part of the shoreline’s rhythm. The painting thus operates as a gentle self-portrait of the painter at work: alert, solitary, attentive to modest things.

Material Presence and the Life of the Surface

Up close, the canvas yields rewards that photographs flatten. Thin spots let the ground tint the sky; thicker strokes in the fish catch the light and create a slight relief; the cliff’s mottling shows the brush’s drag. These variations are not incidental; they are part of how Matisse locates each part of the scene on the spectrum between solidity and air. The fish, with their denser paint, feel moist and immediate; the sky, with its scumbled thinness, feels remote and weightless. The surface becomes a map of sensations where matter and atmosphere occupy the same field.

A Painter’s Ethics: Dignity of the Ordinary

Matisse’s choice of motif and his restraint signal a quiet ethics. He elevates neither the cliff as sublime spectacle nor the fish as anecdotal charm. He treats both with the same seriousness, trusting that attention is what dignifies a subject. In doing so he affirms a modern creed—that art does not require myth or crisis to be consequential; it requires an honest relationship to perception. The modesty of the heap of fish is precisely the point: it anchors the composition and offers a lesson in looking that is democratic and humane.

Relation to Other Works from the Series

Seen alongside other coastal canvases of the same period, “Large Cliff with Fish” occupies a pivotal place. Some pictures from Étretat concentrate on the curve of the bay or the abrupt geometry of the rocks; others dwell on boats or tides. This work threads those concerns through the still-life lens, showing how the discipline Matisse learned in interiors transfers outdoors. It demonstrates his ability to make a whole painting hinge on a small motif without shrinking the landscape’s scope. The picture teaches, by example, how continuity in an artist’s practice—here, the rigorous arrangement of simple forms—can persist across changing subjects.

Interpretive Possibilities: Nourishment, Fragility, and Permanence

The painting lends itself to readings that never strain the image. The fish stand for nourishment and labor; the beach for transience; the cliff for permanence tempered by erosion. Read together, they chart a humane triad: what feeds us now, what changes daily, what abides across decades. There is no moralizing in the arrangement, only a clear-eyed acknowledgment that a life near the sea is bound to cycles larger than intention. If there is a whisper of melancholy, it resides in the knowledge that the fish will soon be gone and the tide will erase footprints. Yet the overall feeling is one of equilibrium, as if the world’s scales, for the moment, are balanced.

Why the Painting Matters Today

A century later, the painting’s quiet intelligence remains bracing. It shows how a modern artist can absorb tradition without mimicry, acknowledge nature without servility, and condense experience into a few poised relationships of color, edge, and weight. In an age that often seeks the spectacular image, Matisse demonstrates the power of steadiness. The picture invites a viewer to practice a slower seeing, to measure distances by touch and temperature rather than by drama, and to find significance in a pile of fish on wet stones.

Conclusion: A Calm Mastery at the Water’s Edge

“Large Cliff with Fish” is a study in compositional poise and human scale. It fuses the permanence of rock, the mutable breadth of the sea, and the immediacy of a day’s catch into a single, breathable surface. The painting’s authority comes from its restraint: a limited palette, a few commanding lines, and a tender attention to ordinary things. Through these means Matisse builds a world that feels inhabited even in the absence of figures, and he renews two venerable genres by bringing them together on a Norman shore. The canvas stands as evidence that clarity can be as daring as intensity, that calm can be as persuasive as spectacle, and that the simplest objects, rightly placed, can hold a horizon in place.