Image source: wikiart.org

A Coastal Image Grounded by Two Rays

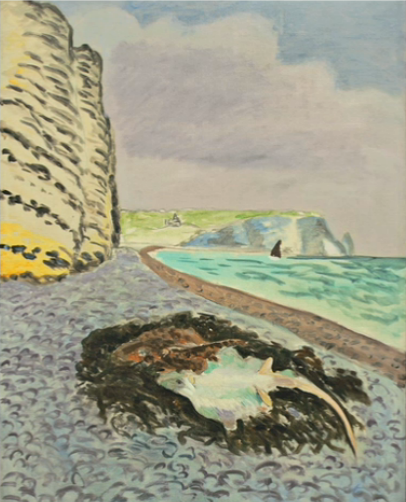

Henri Matisse’s “Large Cliff: Two Rays” (1920) fuses a monumental landscape with the immediacy of a still life to produce a quietly riveting scene. The left side of the canvas is dominated by a chalk cliff whose striations push upward like stacked pages. The right side opens onto a band of turquoise sea, its near edge ribbed by a low, curling wave. Between these two poles stretches a pebbled beach laid in soft, scumbled strokes. At our feet lies the painting’s namesake: two rays, pale and luminous, set upon a dark nest of seaweed. With this modest foreground subject Matisse calibrates the entire space, turning the day’s catch into the anchor that holds cliff, shore, and water together.

Étretat Reimagined After the War

The coastline recalls Normandy’s Étretat, whose chalk walls and sea arches had long captured painters from Courbet to Monet. In 1920, after the First World War, Matisse returned to the sea with a new preoccupation: clarity without spectacle. Rather than chasing storms or dramatic sunsets, he chose a temperate day when light spread evenly, edges softened, and color fell back to its home values. The setting bears the prestige of modern French art history, but Matisse’s agenda is personal. He tests how far he can simplify form and still transmit the sensations of air, stone, water, and the nearness of food.

Composition as a Diagonal Engine

The picture is structured by a single governing diagonal: the sweep of the beach from the lower right foreground to the distant headland. That diagonal transfers energy between the massive vertical of the cliff and the open horizontal of the sea. Matisse reinforces it with subtle cues—the trend of pebble marks, the thin surf line that gleams like a silver thread, and a small, dark sail near the horizon that punctuates the trajectory. The two rays are positioned where this diagonal begins, so every visual journey into depth passes through them. They act as a hinge between near and far, private and public, the tangible present and the airy distance.

Two Rays as a Foreground Still Life

Matisse’s choice of rays, rather than the more familiar heap of mixed fish he used in related canvases, shifts the painting’s character. Rays present strong, planar shapes—rhombus-like bodies with tapering tails—that read instantly from a distance. Their pale green and pearl tones admit delicate reflections, while their cartilaginous forms invite sinuous edges that rhyme with the gentle curve of the waterline. Set upon a bed of brown-black seaweed, they acquire a natural pedestal. The still life is not staged in a studio; it happens where it would happen in life, on the shingle. Because the motif is ordinary, Matisse can treat it with austerity. A few decisive strokes define the rays’ wings, a small daub catches a glint along the spine, and a thin, quick line lays out the tail. Nothing is fussed, and nothing is careless.

Color, Light, and Atmospheric Restraint

The palette concentrates on coastal grays and greens with sparing notes of warmth. The cliff carries chalky yellows and violets that slide into shadow; the sea holds milky aquamarine pushed toward the blue by an under-layer of white; the beach is a low register of slate and lavender. The rays introduce the lightest tones in the painting, pulling attention through value contrast rather than saturation. The overall effect is neither dull nor decorative. It is the poise of a day with thin cloud cover in which color seems lit from within rather than from a single sun. Matisse achieves this with thin paint in sky and sea, letting the weave breathe, and with slightly denser handling in the foreground so the rays feel palpable.

Brushwork, Edges, and the Tangible Surface

Every zone receives its own language of touch. The cliff’s face is built from stacked, horizontal bands, their edges alternately crisp and frayed to suggest fissures and embedded stones. The beach is a field of abbreviated half-moons and commas, marks that imply countless pebbles without counting them. The sea’s surface is brushed more continuously, with long, even strokes that declare it a single plane. In the still life the marks become calligraphic: a spring of the wrist turns a curve into an edge, a loaded brush deposits a highlight that doubles as flesh. Edges carry narrative weight. The cliff’s contour is blunt; the wave’s edge is soft and glassy; the rays’ outlines are elastic. Through edges, Matisse conveys how each thing would feel to the hand—chalk rough, water slick, ray supple.

Measuring Scale Through the Ordinary

The inclusion of the two rays transforms the viewer’s sense of size. Because we instinctively know how large such creatures are, the entire landscape is scaled against them. The cliff grows colossal, the cove widens, the distance lengthens. In this way a simple still life becomes the ruler of the scene. Matisse rejects props that shout—heroic figures, elaborate boats—and relies on a familiar animal to set the measure. The choice grants the landscape a human proportion without inserting a person.

Rhythm, Repetition, and Contrast

The painting is rich in visual rhymes. The triangular suggestions within the rays’ bodies echo the small triangular sail thrusting across the horizontal of the sea. The rays’ tapering tails repeat, in miniature, the receding finger of headland that points toward the horizon. The curve of the eel-like tail is also a gentle counter-curve to the shoreline’s sweep, lending a musical call-and-response between foreground and distance. Matisse balances these rhymes with contrasts: the cliff’s vertical insistence against the sea’s broad lateral calm, the textured pebble field against the smooth water, the dark seaweed against the rays’ pale bodies. The result is a rhythm that moves the gaze without agitation.

Time Scales: Perishability Beside Geology

The motif organizes different tempos of time. The cliff embodies geological duration, its layers recording an almost unreadably long past. The sea, through tide and weather, represents cyclical time, indifferent and dependable. The rays announce immediate time: they are today’s catch, bright for a few hours, then gone. Without a skull or an hourglass or any theatrical vanitas, Matisse allows the coexistence of these tempos to resonate. The painting becomes a meditation on impermanence framed by what endures.

Dialogue with Predecessors and With His Own Work

At Étretat, Courbet emphasized impact—the heavy slap of waves—while Monet specialized in variability—how light and air transform a constant motif. Matisse’s statement is different. He privileges composition as a moral and visual value. The cliff is present but not oppressive; the sea is luminous but controlled; the still life is ordinary but dignified. Within his own practice, the picture extends lessons learned from the interiors of the 1910s, in which bowls, fruits, and patterned cloths were arranged with radical economy. Here the seashore becomes his table, the shoreline his table edge, the seaweed his cloth, the rays his porcelain. He shows that the grammar of still life can order a landscape without turning it theatrical.

Variants in the Coastal Sequence

“Large Cliff: Two Rays” converses with related canvases painted around the same time that feature a heap of fish or a single eel. The shift from many small forms to two large planar forms changes the psychological temperature. The eel version feels calligraphic and lyrical; the mixed-fish version feels abundant and earthy; the rays feel emblematic and serene. Each variant keeps the armature of cliff, beach, and sea, proving that small alterations in the foreground can reorganize the entire mood. The series functions like a set of musical variations on a single theme, evidence of Matisse’s methodical curiosity.

Human Presence Without Figures

No person stands in the frame, yet the scene is shaped by human action. Someone caught the rays, someone placed them on seaweed, someone sailed the small boat that breaks the horizon. The shore bears the unshown labor of fishermen and buyers, of hands that sort, cut, and carry. Matisse hints at this world without illustrating it. The painting grants viewers a solitary vantage over human traces, a quiet moment between work and tide in which looking becomes the work.

Material Surface and the Sensory Field

The painting invites attention to sensory details that extend beyond sight. The pebbles’ cool, rounded pressure underfoot is suggested by the repeated half-moon marks. The seaweed’s wet heaviness is encoded in darker, thicker strokes. The rays’ skin reflects a faint sheen, conveyed by small, lifted highlights. Even the air is palpable: thin paint in the sky allows the canvas weave to act like a fine mist, softening everything at a distance. Matisse’s material decisions translate touch, temperature, and moisture into paint without resorting to descriptive overload.

The Ethics of Attention and the Dignity of the Ordinary

Matisse’s restraint is not a matter of caution; it is an ethic. By refusing spectacle he insists that attention itself dignifies the world. The rays are not trophies. They are simply placed and carefully seen. The cliff is not sublime in the Romantic sense; it is substantial and calm. The sea is not an allegory; it is a continuous surface that breathes. This equanimity gives the painting its authority. Everything is allowed to be itself, and the painter’s task is to establish the precise relations in which each thing can be felt fully.

Symbolic Readings That Grow Naturally from the Image

While the painting resists allegory, it supports readings that arise from its forms. The rays’ flattened bodies, shaped like kites, double as quiet emblems of flight grounded by gravity. Their placement on seaweed suggests a bed or cradle, a temporary rest before the next stage of use. The cliff’s stacked bands can be read as a record of time, the sea as a sheet of possibility, the small sail as human ambition scaled to nature. These meanings are not imposed; they occur because the image is tightly constructed and leaves room for thought.

Space Without Illusion and the Primacy of the Picture Plane

Matisse balances recession with flatness through strategic choices. The cliff touches the left edge like a wall, reminding us we are looking at a painted surface. The sea holds together as a large band of color, its cohesiveness resisting the pull of deep perspective. The beach’s diagonal both leads us inward and presses back against literal illusion by remaining a pattern of marks. Space is present, but the painting never pretends to be a window. It is a surface where sensations are made legible.

Weather, Season, and the Tone of the Day

The day is overcast, with cloud cover that cools color and softens cast shadows. Such weather is an ally of structure. Without the drama of sparkling highlights or black shadows, relationships of value and hue carry the mood. The pale green of the rays can sit near the milky blue of the sea without competition. The cliff’s yellowed lichen can glow modestly against gray. The painting breathes evenly, offering a mood of observant calm well suited to the coastal routine it depicts.

Why the Painting Matters Today

A century later, “Large Cliff: Two Rays” remains instructive for how it achieves intensity without noise. It shows how to make a large space vivid by anchoring it to a small, comprehensible object; how to let color hum rather than blare; how to construct a composition that guides attention while feeling natural. In a culture that often equates significance with spectacle, Matisse’s canvas argues for the enduring power of clarity, measure, and care.

Conclusion: Poise on the Shingle

“Large Cliff: Two Rays” distills an entire world into a handful of relationships. The cliff’s mass, the sea’s breadth, the beach’s diagonal, the rays’ pale bodies on a dark bed—each element is necessary and sufficient. The painting is at once a landscape and a still life, a meditation on time and a celebration of touch, a record of quiet labor and a hymn to ordinary things. Matisse does not ask us to admire his virtuosity; he invites us to share his attention at the water’s edge, where the humblest forms can steady a horizon.