Image source: wikiart.org

A Coastal Meditation Focused by a Single Eel

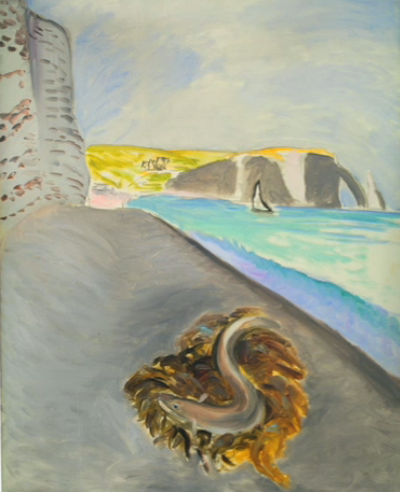

Henri Matisse’s “Large Cliff: the Eel” (1920) stages a meeting between monumental landscape and intimate still life. A chalk cliff rises at the left, a turquoise sea stretches to the right, and a pebbled strand sweeps diagonally through the picture. In the foreground lies a coil of eel on a bed of seaweed, a humble subject that anchors the entire composition. By joining a vast coastal prospect to one glistening creature at our feet, Matisse concentrates grand space into a single point of attention and then releases the gaze outward again. The painting reads as a calm yet alert meditation on looking, where the day’s catch becomes the hinge of vision.

The Setting and Its Lineage

The cliff, the arch in the distance, and the narrow sail hint at Normandy’s Étretat coast, a site canonical in French painting through Courbet and Monet. Matisse’s version is neither storm-tossed realism nor a spectacle of changing light. Instead, he offers a measured harmony: cliffs simplified into pale planes, sea rendered as a sheet of color, and sky kept in a thin veil. The drama lies not in weather but in the structure of the picture and the way near and far converse. By bringing a still life to the shoreline, he quietly revises the site’s tradition and makes it newly his.

Composition as a Balance of Mass and Flow

The canvas organizes itself through three dominant elements. The cliff forms a vertical mass that presses against the left edge, asserting the picture plane. The sea opens a horizontal field to the right, a space of breadth and calm. Between them runs the beach as a diagonal runway, beginning in the lower foreground and leading to the distant arch. The eel sits precisely at the start of this diagonal, where the eye must pass to move deeper into the scene. The coil’s sinuous line echoes the bend of the shoreline and the slow curl of a wave near the waterline, binding motif and setting through shared rhythm. The arrangement is both deliberate and unforced, like a sentence whose grammar you feel before you parse it.

Near and Far Measured Through a Modest Motif

Scale is a crucial pleasure of the painting. The eel furnishes a recognizable measure, translating the beach’s expanse into graspable terms. Because we know how small an eel is, the cliff grows larger, the cove deeper, the headland farther. The still life does not interrupt the landscape; it calibrates it. Matisse trusts a single, ordinary object to carry the responsibility that many painters distribute among figures, boats, or elaborate details. The result is intimacy without sentimentality and distance without melodrama.

Color as Weather and Thought

The palette is restrained yet resonant. Chalky grays and violets describe the cliff; a band of aquamarine gives the sea its cool clarity; the beach is a soft, silvery field. Against these modest hues, the eel and seaweed introduce warmer browns, muted creams, and pearly pinks. None of the colors shout. Thin layers let light seep through; thicker touches lend flesh to the eel. The equilibrium of cool and warm stabilizes the scene while preventing the foreground from detaching. Color here is not spectacle but the means by which environment and object feel joined under one weather.

Brushwork, Edges, and the Sense of Touch

Matisse’s handling is spare and telling. On the cliff face, quick, broken marks suggest embedded stones and pockets of shadow without insisting on geological detail. The sea is brushed in smoother strokes that read as a continuous surface, quiet and slightly glassy. The beach receives soft, scumbled sweeps that keep the pebbles generalized, avoiding the trap of point-by-point description. In the eel and seaweed, the brush turns calligraphic: a single, confident curve locates the body; a small, bright daub catches a glint along the back; loops and zigzags define the tangle of fronds. Each zone of the painting gets its own grammar of edges—blunt for cliff, flowing for water, springy for eel—which tells the hand how each thing would feel.

The Eel as Form, Symbol, and Counterpoint

The choice of an eel is both practical and poetic. Formally, its S-curve offers a flexible line that can rhyme with the shoreline and stand in counterpoint to the cliff’s rigid edge. Its smooth skin takes light beautifully, allowing a few strokes to suggest moisture and weight. Symbolically, the eel belongs to the daily economy of the coast: caught, handled, cooked, forgotten. In the company of the cliff’s geological time and the sea’s cyclical time, the eel embodies immediate time—the perishability of a day’s catch. Without overt vanitas devices, the painting reflects on the brevity of life amid larger, slower continuities.

Landscape and Still Life Joined into One Sentence

Matisse long cultivated still life as a laboratory for composition. Here he transports that laboratory outdoors. The oval of seaweed stands where a platter might sit on a table; the curve of the eel replaces a porcelain rim; the shoreline becomes the table’s edge. Yet none of this reads as a joke or a clever trick. The joining of genres enlarges both: the landscape gains an anchor and a measure, while the still life gains air, movement, and horizon. What could have been a decorative juxtaposition instead becomes a single, coherent sentence spoken in two dialects.

Space Without Theatrical Illusion

Depth unfolds gently from foreground to distance, but Matisse never lets the image become a stage set. The cliff touches the canvas edge, reminding us of the painting’s surface; the sea, though expansive, remains a band of paint; the sky is a thin wash rather than a vaulted dome. This choice aligns with the artist’s aim in the 1920s: to maintain contact with observable nature while respecting the flat field on which painting lives. The result is space that breathes without resorting to tricks of perspective or dramatic chiaroscuro.

The Mood of the Day and the Art of Restraint

Everything suggests an ordinary day: temperate light, still water, quiet air. Matisse consistently prefers this level weather. On such days shadows are soft, edges are diplomatic, and color can settle into its home values. This restraint gives the painting a durable mood—contemplative, receptive, alert rather than ecstatic. The eel, shining modestly in this light, becomes not a trophy but a witness to the coast’s daily cycles. The painting does not perform for us; it invites us to attend.

Dialogue with the Étretat Tradition

By choosing this coastline, Matisse positions himself in dialogue with earlier painters. Where Courbet explored weight and impact, and Monet tracked the variability of light, Matisse turns to equilibrium. The cliff is massive but not crushing; the sea is luminous but not dazzling. The eel in the foreground introduces a domestic note that neither predecessor pursued. This difference is not a rejection but a reframing: he demonstrates that the same site can support many visual arguments, and his is an argument for clarity and poise.

Connections to His Broader Practice

The work belongs to the artist’s postwar pursuit of simplified structure. Around this period he also painted interiors in Nice where objects—flowers, pitchers, patterned cloths—were arranged with economical elegance. The coastal scene applies that economy to outdoor space. You can feel the same discipline: remove the inessential, let a few relationships carry the whole. The eel’s curve is equivalent to a drawn line in a drawing; the cliff’s plane equals a single patch of tone; the sail is no more than a triangular sign. The painting’s power arises from this condensing act.

The Role of the Sailboat and Distant Arch

The small sailboat and the famous arch in the distance serve as punctuation rather than narrative. They mark intermediate stops for the eye on its trip from the eel to the horizon and back. Their scale keeps them from competing with the foreground; their shapes are simple enough to read at a glance. The triangle of the sail introduces a counter-shape to the eel’s curve, and the arch repeats the cliff’s chalky hue in a softened key, reinforcing the unity of the coast. These details are placed with care and then left alone, proof of Matisse’s belief that a painting can be complete with the least possible number of parts.

Material Surface and the Experience of Looking

Viewed up close, the picture’s surface rewards attention. Some passages are thin enough to let the underpainting tint the sky; others, especially in the eel and seaweed, have a slight relief that catches light. These changes of thickness act like dynamics in music, shifting emphasis without breaking the line. Matisse paints not only what is seen but how seeing feels—the slip between solid and fluid, the shimmer where light rides a curve, the way a mass keeps its place when a breeze passes. The canvas becomes a record of those sensations made steady.

Humanity Without Figures

No figures inhabit the beach, yet traces of human presence are everywhere. Someone caught the eel, someone placed it on the seaweed, someone sailed the boat that pricks the horizon. The painting implies a social world while granting solitude to the viewer. We occupy the position of a person who has paused mid-walk to study the catch and then lifted their head to the distance. It is a quiet, unrushed vantage that suits the painting’s ethic of attention.

Time, Tide, and the Quiet Drama of Change

The eel’s perishability, the tide’s habitual approach, and the cliff’s slow erosion stage a layered sense of time. Nothing in the scene is frozen, yet nothing is frantic. The painting acknowledges that change proceeds at different speeds in different things and that perception can accommodate those scales simultaneously. This is the quiet drama: a creature that will not last the afternoon lies beneath a cliff that has stood for ages, with a tide that will erase footprints by evening. Matisse composes these tempos into a chord rather than a plot.

The Ethics of Looking and the Dignity of the Ordinary

A consistent thread in Matisse’s work is the belief that attention ennobles ordinary subjects. “Large Cliff: the Eel” exemplifies that belief. No heroic narrative is needed; no emblem of myth is required. A single eel, painted with care and placed in exact relation to cliff and sea, carries the full gravity of the picture. The dignity here belongs not to rarity but to rightness: the right stroke at the right place, the right color beside another, the right pause of empty space. The painting proposes that such rightness is a form of kindness to the world.

Relation to Companion Works

The image resonates with other canvases of the same coastline in which Matisse adjusts the foreground motif—a general heap of fish in one, an eel in another—while keeping the armature of cliff, beach, and sea. Comparing them reveals how a small change of object recalibrates mood and emphasis. The eel’s single, supple curve gives this version a more lyrical thrust than its companions; the foreground acts less like a pile and more like a calligraphic sign. The series as a whole shows the painter testing how minimal variations can reorganize the whole visual sentence.

Why the Painting Endures

The work endures because it embodies a paradox that modern art cherishes: simplicity that contains complexity. With a handful of shapes, a narrow palette, and a trust in placement, Matisse opens a wide field of feeling—fresh air, damp pebbles, a briny gleam, the hush of a mild day, the nearness of food, the distance of headlands, the slow turning of tide. The painting neither dazzles nor declaims; it steadies the mind and makes room for attention to do its deep work. That poise, achieved through painterly means alone, is its lasting accomplishment.

Conclusion: A Calm Mastery at the Edge of Water

“Large Cliff: the Eel” gathers a coastline, a creature, and the act of seeing into a lucid whole. The cliff presses, the sea opens, the beach guides, and the eel coils like a signature that fixes the page. Every element serves the balance of the image, and nothing is superfluous. In a single, breathable surface, Matisse shows how the grand and the ordinary complete one another. The picture is a hymn to clarity, to modesty, and to the quiet power of form—an invitation to pause at the water’s edge and understand how much a painter can say with very little.