Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

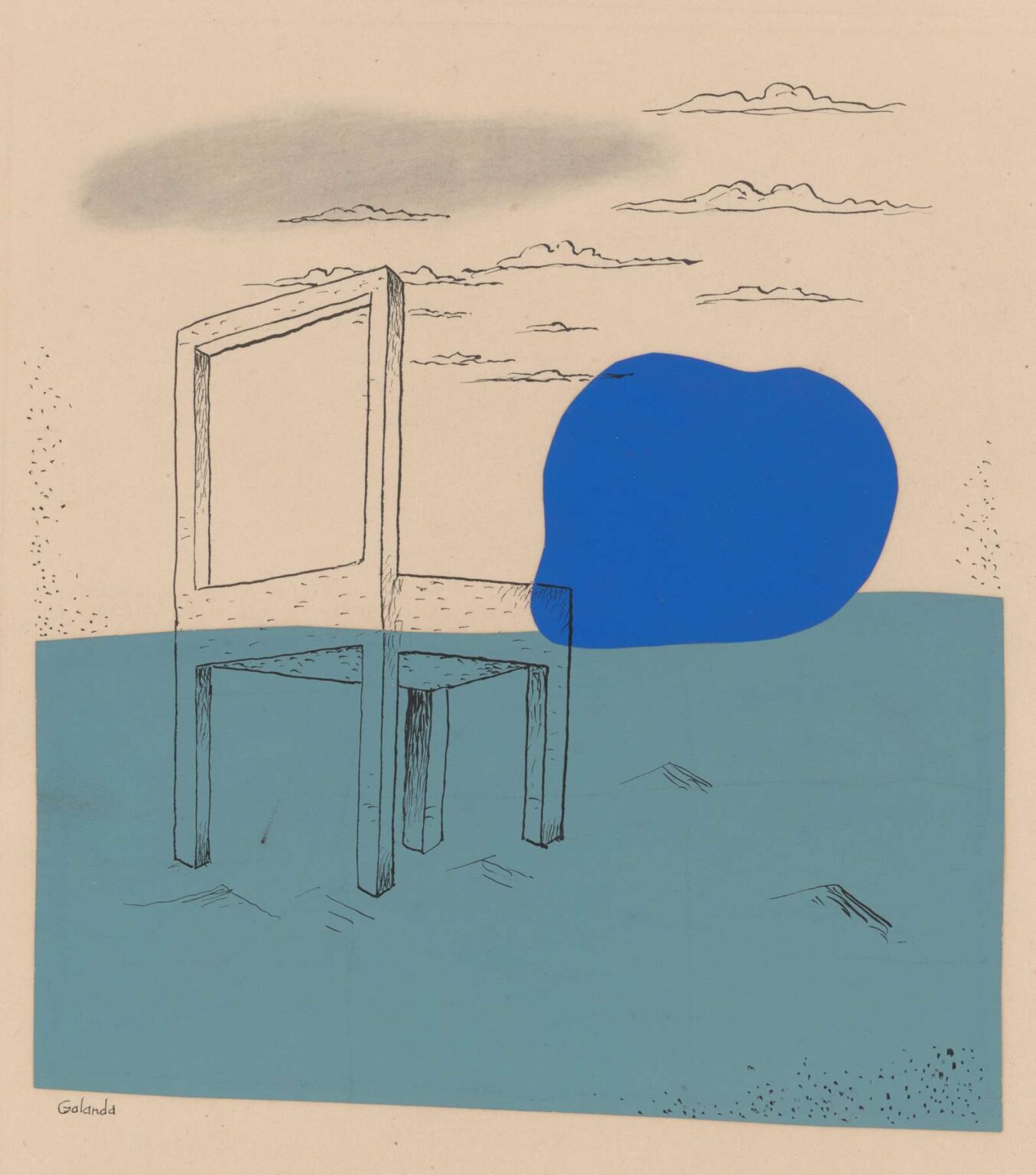

Mikuláš Galanda’s Landscape with a Chair (1930) is a compelling fusion of graphic precision and lyrical abstraction, inviting viewers into a subtly surreal world where everyday objects assume new psychological weight. At first glance, the sketch of a simple chair appears almost prosaic, but Galanda transforms it—through strategic placement, line work, and bold color fields—into a poetic signifier of absence, contemplation, and the mutable boundary between interior and exterior experience. This extended analysis will explore the painting’s historical context, Galanda’s artistic journey, its formal composition, use of line and color, symbolic resonances, technical execution, and enduring influence in the broader narrative of Slovak modernism and European avant‑garde movements.

Historical and Cultural Context

In 1930, Czechoslovakia was navigating its first decade of independence, seeking to define a national identity while absorbing international artistic innovations. The interwar period saw the rise of various avant‑garde groups in Bratislava and Prague, including Nová Trasa—which Galanda co‑founded—championing art grounded in folk heritage yet open to Cubist, Constructivist, and Surrealist influences. Landscape with a Chair emerges at a moment when artists experimented with everyday motifs stripped of narrative context to probe deeper psychological and formal concerns. Galanda, drawing on his training in Budapest, Munich, and Vienna, synthesized these threads into a distilled visual language that bridged graphic art and painting, documentary observation and dream imagery.

Mikuláš Galanda’s Artistic Evolution

Mikuláš Galanda (1895–1938) began his career steeped in academic draftsmanship, later embracing woodcut and lithography before exploring mixed‑media works. Co‑founding Nová Trasa in 1928, he advocated for clarity of form, social relevance, and the re appropriation of folk motifs. By 1930, Galanda’s style had matured into a hybrid of measured geometry and spontaneous mark‑making. Landscape with a Chair exemplifies this evolution: the chair’s orthogonal frame recalls his graphic roots, while the amorphous color shapes and sketched clouds reveal a freer, more intuitive impulse. This work marks a transitional phase in his oeuvre, where he bridged representational fidelity and poetic abstraction.

Composition and Spatial Structure

Galanda structures Landscape with a Chair around a central axis defined by the chair’s backrest and seat. The chair is rendered in delicate pen‑and‑ink lines, floating as if set upon a horizontal swath of pale blue that delineates ground from sky. Above, the sky is sparsely populated by wispy, graphite-rendered clouds. To the right of the chair, a large, irregular blue shape intrudes upon the composition, its amorphous form contrasting the chair’s rigid geometry. This bold patch of color balances negative space elsewhere, creating a dynamic tension between containment and openness. The viewer’s eye moves effortlessly between the drawn chair, the color field, and the minimal horizon line, fostering a sense of both stillness and latent movement.

The Chair as Psychological Anchor

The chair, a ubiquitous domestic object, acquires unexpected depth under Galanda’s hand. Its linear rendering—complete yet slightly off-kilter—suggests both a tangible seat and a symbolic threshold between presence and absence. Empty, it evokes notions of solitude, invitation, or the memory of an unseen sitter. In the surrounding landscape devoid of other objects or figures, the chair becomes a psychological anchor, prompting questions: Who might have sat here? What thoughts did they entertain? Galanda’s placement of the chair at the foreground’s edge further emphasizes its liminal quality, as if it straddles two realms—the known interior and the enigmatic exterior.

Line Quality and Graphic Precision

Galanda’s mastery of line is evident in the chair’s rendering. Each edge is defined by confident, textured strokes that vary in weight—a testament to his background in woodcut and lithography. The seat’s underside, sketched with light cross‑hatching, suggests depth without overwhelming solidity. The chair’s front leg descends into the blue ground field, where its outline gently dissolves, further underscoring the boundary between object and environment. Above the horizon, thin, fluid lines sketch clouds and atmospheric haze, their brevity balancing the chair’s more substantial contours. Through these line variations, Galanda constructs a visual dialogue between rigor and spontaneity.

Color Fields and Tonal Harmony

The most arresting feature of Landscape with a Chair is the juxtaposition of two distinct color fields: the horizontal aquamarine plane that supports the chair and the amorphous cobalt shape to its right. These hues, chosen from a restrained palette, resonate with each other—both are cool tones that evoke water and sky—yet they differ in saturation and boundary: one is crisp and rectilinear, the other diffuse and organic. The surrounding paper’s warm beige ground provides a neutral counter‑balance, ensuring that the blue elements read as intentional insertions rather than background stains. Galanda’s economy of color underscores the painting’s meditative quality, allowing form and line to remain paramount.

Atmospheric Indications: Clouds and Horizon

Stormy or serene, the sky in Landscape with a Chair is suggested by minimal means. A soft graphite smudge hovers above the chair—a cloud bank or distant haze—while delicate ink lines sketch smaller clouds across the horizon. The horizon itself is implied by the meeting of vertical chair legs with the blue ground field, reinforced by a faint pencil line that bisects the composition. These subtle atmospheric cues situate the otherwise abstracted scene within a natural setting, reminding viewers that reality persists even in pared-down representations. Galanda’s restraint invites contemplation of sky and earth, object and void.

Symbolic Resonances and Allegorical Possibilities

Beyond its formal sophistication, Landscape with a Chair brims with symbolic potential. The empty chair can signify vacancy, expectancy, or the passage of time—an emblem of solitude or open hospitality. The two blue fields may reference water and sky, life’s essential elements, or the fluidity of consciousness. The sketched clouds echo the impermanence of thought and memory. As an allegory, the work suggests that objects and landscapes are intertwined with human perception: a chair placed in nature becomes a vessel for projection, a prompt for reflection. Galanda’s choice to leave interpretation open-ended aligns with modernist interest in viewer engagement and multiplicity of meaning.

Technical Execution and Media

Landscape with a Chair combines pen‑and‑ink drawing with applied color—likely gouache or tempera—on paper. The pen work is precise, employing fine nibs for thin cloud outlines and broader strokes for the chair’s frame. The blue fields exhibit solid, flat application, indicating the use of an opaque medium. The paper’s texture shows through the color in places, creating a rich surface interplay. Such mixed‑media techniques reveal Galanda’s fluency across disciplines: his graphic background informs the linear elements, while his painterly sensibility guides color placement. This hybrid approach was innovative in Slovak art of the era and contributed to his reputation as a versatile modernist.

Relation to European Avant‑Garde Currents

In the broader context of 1930s European art, Landscape with a Chair resonates with Surrealist and Constructivist explorations of everyday objects in unexpected settings. Artists like Giorgio de Chirico placed chairs and architectural elements in metaphysical landscapes, invoking mystery and dream logic. Meanwhile, Constructivists pushed geometric forms and bold color fields. Galanda’s work synthesizes these impulses: the chair’s precise geometry echoes Constructivist discipline, while its placement in an ambiguous landscape points toward Surrealist enigma. Yet he retains a distinctly Slovak voice, eschewing theatrical staging in favor of quiet contemplation.

Viewer Engagement and Interpretive Space

By presenting a familiar object out of context and surrounding it with large color washes and minimal atmospherics, Galanda creates a painting that feels both inviting and elusive. Viewers are drawn to the chair’s details—the grain of the ink lines, the subtle cross‑hatching—while also compelled to consider the emptiness around it. The blank paper borders function as a metaphorical stage curtain, framing the scene and reminding us of the painting’s constructed nature. This interplay of presence and absence encourages active engagement: one must supply the missing narrative threads and emotional undercurrents, making each encounter with the work a unique act of co-creation.

Landscape with a Chair in Galanda’s Oeuvre

While Galanda is best known for his paintings of figures and folk motifs, Landscape with a Chair occupies a singular place in his catalog of work. It exemplifies his graphic phase—periods when he privileged line, tonal contrast, and minimal color over elaborate composition. The piece foreshadows his later experiments with text and image integration, as well as his pedagogical efforts to teach clarity of form. Though less frequently reproduced than some of his more figurative works, Landscape with a Chair remains a vital testament to Galanda’s restless innovativeness and his capacity to endow simple motifs with profound resonance.

Legacy and Influence

Landscape with a Chair has influenced subsequent generations of Slovak and Central European artists seeking to bridge graphic art and painting. Its economy of means and openness to interpretation resonate with contemporary minimalists and conceptual artists who view objects as carriers of meaning beyond their utilitarian function. The work is frequently studied in academic courses on interwar modernism, illustrating how local practitioners like Galanda absorbed international currents while forging personal visual vocabularies. Exhibitions on metaphysical landscapes often include this piece to highlight the dialog between the quotidian and the enigmatic.

Conservation and Display Considerations

As a mixed‑media work on paper, Landscape with a Chair requires careful conservation. The paper substrate benefits from acid‑free mounting and UV‑filtered framing to prevent discoloration of both the ink lines and the opaque color fields. Controlled humidity and temperature settings protect against paper warping and pigment migration. When displayed, even, diffused lighting preserves the work’s subtle tonal relationships without risking fading. Institutions housing the painting often rotate it with related works by Galanda to minimize light exposure, ensuring its longevity for future study and enjoyment.

Conclusion

Mikuláš Galanda’s Landscape with a Chair (1930) stands as a masterclass in the transformative potential of everyday objects when framed by inventive line work and bold color. Through the juxtaposition of a meticulously drawn chair and expansive blue fields, Galanda invites viewers into a space where the familiar becomes uncanny, and the boundary between interior consciousness and exterior reality dissolves. The painting’s formal elegance, symbolic depth, and technical innovation secure its place among the landmarks of Slovak modernism and its dialogue with European avant‑garde movements. Nearly a century later, Landscape with a Chair continues to engage and inspire, proving that even the simplest motif—an empty chair—can become a vessel for limitless reflection.